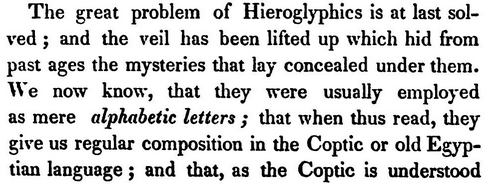

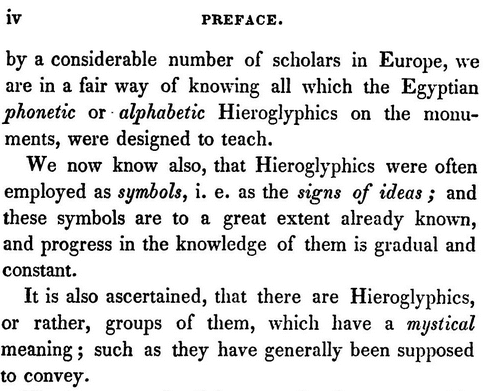

The Rosetta Stone was discovered in 1799. While Thomas Young and other scholars studied it and made some progress in better understanding Egyptian through its clues, it was Jean François (1790-1832) who has received the credit for cracking the mysteries of the Egyptian language, even though with the progress he made he still couldn’t read the Rosetta Stone. But he did reveal that Egyptian hieroglyphs were phonetic, though they could also provide symbolic meaning. His work created an instant sensation in Europe. As E.A.W. Budge wrote in The Mummy, chapters on Egyptian funerary archaeology (Cambridge: Oxford Univ. Press, 1893), 130, available at Archive.org:

[On September 17, 1821, Champollion] read his Mémoire on the hieroglyphics and exhibited his hieroglyphic Alphabet, with its Greek and Demotic equivalents, before the Académie des Inscriptions. Champollion’s paper created a great sensation, and Louis XVIII wished a statement concerning it laid before him, and M. le Duc de Doudeauville determined that an Egyptian Museum should be formed in the Palace of the Louvre. In the same year Champollion published his Lettre à M. Dacier, relative à l’Alphabet des Hiéroglyphes phonétiques, in which he showed beyond a doubt that his system was the correct one. In a series of Mémoires read at the Institut in April, May and June, 1823, he explained his system more fully, and these he afterwards published together entitled Précis du Système Hiéroglyphique des Anciens Egyptiens, Paris, 2 vols., 1824. A second edition, revised and corrected, appeared in 1828.

Could this sensation remain known only to the Europeans for over a dozen years? Could American Egyptomaniacs in 1835 in places like Ohio be treated to visits from seasoned international travelers like Michael Chandler and be stirred by contact with actual Egyptian mummies and scrolls but not hear word of the sensational news of Champollion’s work?

Archive.org provides a noteworthy 1830 book on Champollion’s work that was published in American during a time of strong interest in all things Egyptian. The book is Essay on the hieroglyphic system of M. Champollion, jun. by J. G. Honoré Greppo with translations by Isaac William Stuart (Boston: Perkins and Marvin, 1830, 2nd ed. 1842). The scanned book is the 2nd edition printed in 1842, though Archive.org lists it under the original 1830 publication date. The physical volume is in the George Fabyan Collection in the Library of Congress.

Moses Stuart wrote the following from the Theological Seminary in Andover in 1830 in his introduction to Greppo’s book:

While knowledge of Champollion’s work may have taken a while to spread from Europe in the early 1820s to the United States, it could not have remained a secret for long. Or did it?

If one is going to claim that the vast tide of American “Egyptomania” drove Joseph and the Saints to their over-zealous quest to not only purchase mummies and scrolls, but also to study the scrolls and seek to translate them, then we must also recognize that the presence of Egyptomania would also mean that Champollion and his work would not remain unknown for long to the early Saints. I believe Val Sederholm of the excellent “I Began to Reflect” blog once said something like, “You can’t have Egyptomania in 1835 without Champollion.”

Joseph and his peers had reached out to Charles Anthon, they had met Chandler and purchased mummies and scrolls, they had spread the word about their curiosities and received numerous visitors, not to mention the occasional convert from afar. If America or at least Ohio was wrapped up in Egyptomania, then how could Joseph and his friends shield themselves from the news that 12 years earlier, Champollion’s work had born fruit and was overthrowing ridiculous old theories about the Egyptian language? How could they not have heard the news that Egyptian was indeed known to be a phonetic language, a running language written like Hebrew or other languages, one that could convey the spoken language of an ancient people (in addition to symbolic content, of course)? It seems likely that this had become known to them in some way by the time or shorty after the time Joseph encountered Michael Chandler and bought the scrolls.

How, then, is it possible that Joseph could have imagined that a single character could convey an overflowing cornucopia of words? How could he or any scribe imagine that Joseph could turn a squiggle not just into many words, but a detailed story with specific names and intricate details involving numerous concepts?

Greppo’s witness is not alone. Just as Greppo’s 1830 book was coming out, documents from another source in the United States would provide another independent witness sharing plausible views relevant to the nature of Egyptian writing, consistent with it being phonetic and able to represent the evolving language of an ancient people, and that it was a “running” language, one that could be written like Hebrew to convey knowledge that could be read and deciphered. You may be thinking of other articles or reports of the day from various scholars and journalists, but the example I’m thinking about may surprise you. I am referring to statements and documents from Joseph Smith himself, the extraordinary translator of reformed Egyptian language, which he described as a “running” language like Hebrew and other languages, and, in his grand manuscript for the Book of Mormon, indicated through the translated writings of Mormon (Mormon 10:32) that:

[W]e have written this record according to our knowledge, in the characters which are called among us the reformed Egyptian, being handed down and altered by us, according to our manner of speech.

It reflected speech. It was phonetic, or at least the reformed script Mormon referred to, like the reformed Egyptian script of demotic.

On the Joseph Smith Papers website, you can see this quote from Joseph as he discusses the title page of the Book of Mormon, which came from the last plate (not the last character!) in the Nephite record:

I would mention here also in order to correct a misunderstanding, which has gone abroad concerning the title page of the Book of Mormon, that it is not a composition of mine or of any other man’s who has lived or does live in this generation, but that it is a literal translation taken from the last leaf of the plates, on the left hand side of the collection of plates, the language running same as all Hebrew writing in general.

It was a running language. Not an utterly mystical one where each squiggle could be paragraphs of English. With his experience in reformed Egyptian behind him, does it stand to reason that once he saw the Egyptian scrolls in 1835, he would suddenly reverse course and see it as pure mysticism completely unlike Hebrew, no longer phonetic or a running language? If so, his comments on the meaning of the Facsimiles are remarkably concise, and he speaks of simple meanings to be found in the (plural) characters above some figures. No sign of a magic compactness.

Understanding Joseph’s statements and witness about the nature of (reformed) Egyptian, we should not be surprised to see Phelps in his 1835 notebook equating around 50 Egyptian characters to around 50 English words. The later added “in part” in barely visible pencil does not negate what he inked, nor the obvious logic behind it, though his translation is erroneous. It cannot mean that the Egyptian Joseph had been translating was now one character for large blocks of English, even if you think he dreamed of a pure language that could do such.

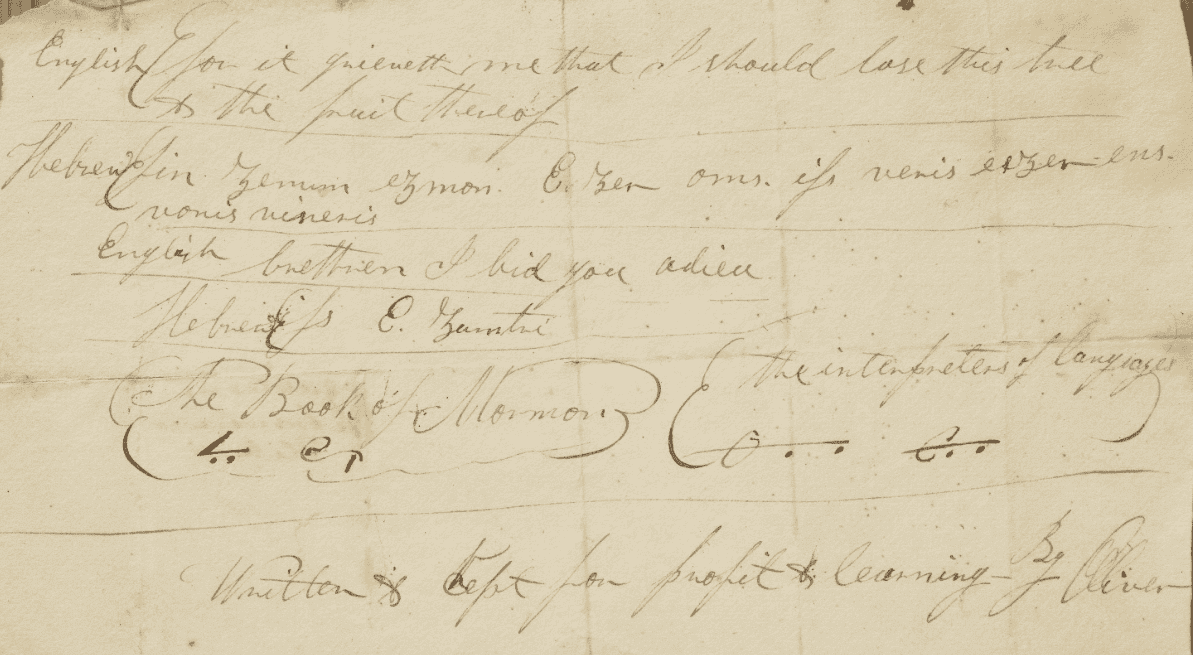

For further verification, please look at another document from Oliver Cowdery in 1835 to 1836 which gives us some insight into the “comprehensive” nature of the Egyptian language that Cowdery once spoke of. The document is listed on the Joseph Smith Papers website as “Appendix 2, Document 2a. Characters Copied by Oliver Cowdery, circa 1835–1836.” The document, apparently in the handwriting of Oliver Cowdery, gives a few words of English, a transliteration of the Hebrew translation, and then shows two pairs of Egyptian-like characters beneath a pair of English phrases: “(The Book of Mormon)” and “(the interpreters of languages).” (Hat tip to Val Sederholm.)

|

| Cowdery equates a four characters of reformed Egyptian to eight words of English

(4 of which are “the” and “of”) |

Two characters for “the Book of Mormon” and two for “the interpreters of languages.” Sure, it’s compact and concise — but not ridiculously and impossibly so. And frankly, in my uneducated opinion, those presumably reformed Egyptian characters could easily fit in with the Egyptian script on the Joseph Smith Papyri, another version of reformed Egyptian. “Reformed Egyptian,” of course, is not a specific name of a language — “reformed” is just an adjective describing the evolution and revision that had occurred in the Nephites’ Egyptian script for sacred records, just as real Egyptian had variants that evolved into forms of hieratic or demotic.

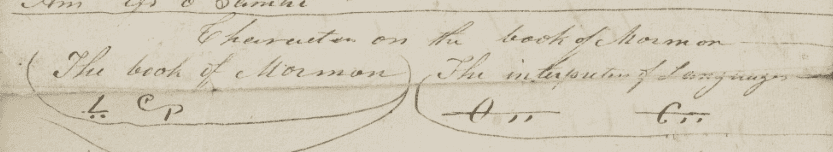

It wasn’t just a private, wild idea from Oliver that maybe Egyptian wasn’t magically, bizarrely compact. As previously discussed, W.W. Phelps in a notebook equated a chunk of Egyptian with a reasonably sized chunk of English — a sensible view of what how much data an Egyptian or reformed Egyptian character could convey. But they may not be alone among Joseph’s scribes on this view. Consider also the document below from Frederick G. Williams, listed as “Appendix 2, Document 2b. Writings and Characters Copied by Frederick G. Williams, circa Early to Mid-1830s.” It apparently copies part of Cowdery’s document, and was written by 1837 or earlier. These men, at least for a while, had a relatively reasonable view about what language could do. Whatever Phelps, Williams, and Warren Parrish thought they were doing when the placed one character to the left of some large chunks of Book of Abraham English text that Joseph had already translated, it simply makes no sense that they had lost all sense of proportion and had forgotten what they should have learned from the Book of Mormon and Joseph’s statements, if not their own. I don’t know what they were doing, but their later and quickly abandoned work simply does not reflect how Joseph translated the Book of Abraham or the Book of Mormon. It’s time to recognize that. Crazed expansion fueled by a Champollion-free world of Egyptomania in 1835 does not provide a reasonable explanation of the translation of the Book of Abraham.

|

| Frederick G. Williams copied the characters and translation from Cowdery |

This post is part of a recent series on the Book of Abraham, inspired by a frustrating presentation from the Maxwell Institute. Here are the related posts:

- “Friendly Fire from BYU: Opening Old Book of Abraham Wounds Without the First Aid,” March 14, 2019

- “My Uninspired “Translation” of the Missing Scroll/Script from the Hauglid-Jensen Presentation,” March 19, 2019

- “Do the Kirtland Egyptian Papers Prove the Book of Abraham Was Translated from a Handful of Characters? See for Yourself!,” April 7, 2019

- “Puzzling Content in the Egyptian Alphabet and Grammar,” April 14, 2019

- “The Smoking Gun for Joseph’s Translation of the Book of Abraham, or Copied Manuscripts from an Existing Translation?,” April 14, 2019

- “My Hypothesis Overturned: What Typos May Tell Us About the Book of Abraham,” April 16, 2019

- “The Pure Language Project,” April 18, 2019

- “Did Joseph’s Scribes Think He Translated Paragraphs of Text from a Single Egyptian Character? A View from W.W. Phelps,” April 20, 2019

- “Wrong Again, In Part! How I Misunderstood the Plainly Visible Evidence on the W.W. Phelps Letter with Egyptian ‘Translation’,” April 22, 2019

- “Joseph Smith and Champollion: Could He Have Known of the Phonetic Nature of Egyptian Before He Began Translating the Book of Abraham?,” April 27, 2019

- “Digging into the Phelps ‘Translation’ of Egyptian: Textual Evidence That Phelps Recognized That Three Lines of Egyptian Yielded About Four Lines of English,” April 29, 2019

- “Two Important, Even Troubling, Clues About Dating from W.W. Phelps’ Notebook with Egyptian “Translation”,” April 29, 2019

- “Moses Stuart or Joshua Seixas? Exploring the Influence of Hebrew Study on the Grammar and Alphabet of the Egyptian Language,” May 9, 2019

- “Egyptomania and Ohio: Thoughts on a Lecture from Terryl Givens and a Questionable Statement in the Joseph Smith Papers, Vol. 4,” May 13, 2019

- “More on the Impact of Hebrew Study on the Kirtland Egyptian Papers: Hurwitz and Some Curiosities in the GAEL,” May 20, 2019

- “He Whose Name Cannot Be Spoken: Hugh Nibley,” May 27, 2019

- “More Connections Between the Kirtland Egyptian Papers and Prior Documents,” May 31, 2019

- “Update on Inspiration for W.W. Phelps’ Use of an Archaic Hebrew Letter Beth for #2 in the Egyptian Counting Document,” June 16, 2019

- “The New Hauglid and Jensen Podcast from the Maxwell Institute: A Window into the Personal Views of the Editors of the JSP Volume on the Book of Abraham,” July 1, 2019

- “The Twin Book of Abraham Manuscripts: Do They Reflect Live Translation Produced by Joseph Smith, or Were They Copied From an Existing Document?,” July 4, 2019

- “Kirtland’s Rosetta Stone? The Importance of Word Order in the ‘Egyptian’ of the Grammar and Alphabet of the Egyptian Language,” July 18, 2019

- “The Twin BOA Manuscripts: A Window into Creation of the Grammar and Alphabet of the Egyptian Language?,” July 21, 2019

- “A Few Reasons Why Hugh Nibley Is Still Relevant for Book of Abraham Scholarship,” July 25, 2019

Jeff, when you speak of Joseph’s “experience in reformed Egyptian,” are you referring to his experience in reading English words as they appeared supernaturally on a seer stone buried in his hat while the reformed Egyptian characters on the plates were in another room? I’m not sure that kind of experience would lead to much in the way of linguistic insight.

I do, however, appreciate your admission that people like Joseph could know stuff without possessing a “vast frontier library.”

Someday you will see the light. Not today or tomorrow, perhaps — but someday. If Brian Hauglid can do it, so can you.

— OK

Jeff, I like your question about the possibility of JS moving from a character representing maybe 4 words to representing a paragraph or more. Doesn’t the GAEL provide a model for that? In the GAEL how much text a single character offers is determined by it’s degree. The higher the degree the more the detail. The concept of degree offers a wide flexibility. That being said, I do recognize that the BoA manuscripts show even more text for many of the characters than even the 5th degree of the GAEL. I wonder if JS believed or developed a belief while translating that there was possibly more than the 5th degree, which lent even more text per character. This is obviously conjecture, but I wouldn’t be surprised if he believed that Abraham utilized Egyptian even more powerfully than the normal 5 degrees outlined in the GAEL.

OK, he and others saw the characters and copied some of them. From his miraculous translation work, he could understand the relationship between characters and text. He could see that the characters on the last leaf gave the translated title page. He could see that it was a running language, and apparently he noticed that two characters meant “Book of Mormon.” That’s experience. He knew that one scrawl doesn’t give you a page of text.

Jeff, you’re assuming the plates actually existed, an assumption I and many others do not share. It would be great to see you base your analysis solely on the artifacts we actually possess, and the facts as they are generally agreed upon, without recourse to things knowable only by recourse to the spirit. Like the JSP scholars have been so ably doing.

— OK

Back to your actual argument in this post. You make some incredible inferences, e.g. when you write things like this:

I am referring to statements and documents from Joseph Smith himself, the extraordinary translator of reformed Egyptian language, which he described as a "running" language like Hebrew and other languages, and, in his grand manuscript for the Book of Mormon, indicated through the translated writings of Mormon (Mormon 10:32) that:

[W]e have written this record according to our knowledge, in the characters which are called among us the reformed Egyptian, being handed down and altered by us, according to our manner of speech.

It reflected speech. It was phonetic, or at least the reformed script Mormon referred to, like the reformed Egyptian script of demotic.

You make the transition far too easily from —

altered by us, according to our manner of speech

to

It reflected speech. It was phonetic.

It seems to me you're getting really far out over your skis here, Jeff. "Altered according to" does not necessarily mean "reflected," right? Yet out of the many possible meanings of "characters altered according to our manner of speech," you fix on this one meaning, the one that just happens to support your argument.

"Manner of speech" could refer to many things. It could mean "We speak in an informal style." It could mean "We speak in complete sentences." It could mean "We speak succinctly" or (much more likely in the case of gasbaggy Book of Mormon) "We speak in a very dilatory way." It could mean "We speak of religious matters using a special register reserved for that purpose."

All of these possibilities strike me as much more likely than the one you've glommed onto because they are actually manners of speaking. Speaking phonetically, by contrast, is not a "manner of speech," it is speech itself. An ancient writer might sensibly say "I'm speaking confidentially here," or "I'll be speaking formally in my address to the people," and these would be "manners of speech." But why would one say "I'm speaking phonetically — you know, using sounds formed in my mouth"?

But enough. It's so silly that even this much needs to be said.

— OK

Another big assumption is that “the language running same as all Hebrew writing in general“ doesn’t just mean the characters were meant to be read right to left.