David Charles Gore, The Voice of the People: Political Rhetoric in the Book of Mormon (Provo, UT: Neal A. Maxwell Institute, 2019). 227 pages.

As one interested but perpetually disappointed in modern politics, I began reading David Gore’s The Voice of the People seeking to better understand what guidance the Book of Mormon might have about the fractious nature of modern politics. Some readers may out of habit shy away from books that threaten to discuss politics, and perhaps some conservatives might expect disappointment in a book from a humanities professor (Gore is a Professor and Head of the Dept. of Communication at the University of Minnesota Duluth) since modern academia tends to lean toward one end of the political spectrum, especially in the humanities. Fortunately, people of almost any political persuasion can benefit from Gore’s even-handed and thoughtful discussion. Indeed, one need not be Latter-day Saint to enjoy this book and find helpful, refreshing insights into how to be a better citizen and work more effectively and harmoniously with others whose views are sharply different. Ultimately, Gore and the Book of Mormon show us how to better accept the diversity of our communities and not let it be a barrier to our own engagement in civic and religious matters.

The significance of what Gore is doing with his analysis of the Book of Mormon most fully hit me when I read his thought-provoking conclusion which nicely frames many of the issues considered throughout the book. I went from enjoying his book to suddenly deeply appreciating it.

This book is not about what the Book of Mormon has to say about politics or the pros and cons of any particular political viewpoint or form of government, but about what the ancient Book of Mormon can teach us about how to cope with some of the most difficult and fractious challenges in our societies, the challenges of political divides, of contention that can escalate into civil war and mountains of casualties, even the collapse of civilization itself. Understanding the lessons of this remote “voice from the dust” can give powerful, practical guidance to citizens and their leaders today in how to engage in the political process rather than repeating the mistakes that so many societies and civilizations have made.

While the Book of Mormon is clearly a religious text, its influence is public and

cannot be limited to religion alone. Two leading historians regard the

Book of Mormon as “one of the greatest documents in American cultural

history” and “among the great achievements of American literature.”

In this regard, the Book of Mormon’s effects and consequences

are vast, uncontained and uncontainable. Yet within these effects and

consequences is good evidence that the Book of Mormon makes a real

and serious contribution to understanding the human predicament. By

bringing the Book of Mormon to bear on the philosophical problems

of public discourse, my aim is to show the power and relevance of its

claims for politics and society. (pp. 1-2)

The answer is not to be found in supporting and enforcing any one party’s agenda, but in learning and applying the weightier matters taught by the Book of Mormon regarding the political process and the way we engage in it. The power of the “voice of the people” is not realized by having those with better political views outshout their opponents, but in learning how to shoulder the responsibilities that our political freedoms require us to bear, and how to engage in politics without losing politeness, without seeing those with other views as enemies to silenced but as fellow humans to be respected. The most vital messages of the Book of Mormon for our day in the arena of politics and public discourse are not about achieving victory in numbers, but about achieving victory in one heart at a time as men and women learn to serve and “be for others” instead of seeking their own selfish agendas. The Voice of the People is infused with a call for each of us to have more love, more patience, and more polite discourse, even when others abandon such standards. There are profound lessons in Book of Mormon on political discourse and rhetoric which are beautifully drawn out by Dr. Gore. While some may object that such views are too idealistic and don’t deal with the practical reality of chaos and corruption in society, it is precisely those realities which demand something more than typical response of the natural man seeking his or her own interests in order to achieve a better, less contentious outcome:

A central preoccupation of this book is to puzzle out how we should talk to each other and how we can realize better communities, knowing that we live and work in contexts where things can and do fall apart, where institutions and people are corruptible. (p. 17)

Gore focuses on the era that begins when King Mosiah faced a succession crisis and chose to transform the political system of the Nephites. King Mosiah had just absorbed the lessons of the failed Jaredite nation as well as the failure of the small colony of King Noah and his corrupt court, and realized more fully the dangers of a government of kings. His dramatic change to a system of judges based in some way on “the voice of the people” involved extensive preparation and political discourse to prepare his people for the new levels of responsibility in the new system. Gore brings out numerous details and insights that readers have likely overlooked. I especially enjoyed seeing the allusions made to the Old Testament in this process, which add further meaning to the Book of Mormon text. I was especially intrigued with his observation about the importance of Judges 21:25 on the text, where we read that “In those days there was no king in Israel: every man did that which was right in his own eyes.” In King Mosiah’s discourse with the people, Gore sees an interaction with Judges in Mosiah’s “every man” in his teaching that “that the burden should come upon all the people, that every man might bear his part” (Mosiah 29:34).

Gore goes much further and shows an interesting relationship between the discussion supporting the case for monarchy in the Old Testament (especially Judges and 1 and 2 Samuel) and Mosiah’s discourse. In a fascinating inversion, the issues and rhetoric in the Old Testament used to support monarchy are echoed by Mosiah but to build the case for abolishing it, one of many interesting avenues pursued by Gore. For example:

In Judges, “his own eyes” suggests the wanderer walks after his own desires and that he has no guide or leader. Contrast this to the phrase “his own sins,” where the wanderer recognizes his estrangement and views his life as a sojourn and pilgrimage, a temporary stay on the way to somewhere else, somewhere he more fully belongs. Somewhere he can be set to rights. This passage from Mosiah hears the words of Judges and amplifies them in a rejoinder. Mosiah turns the constitutional and literary theme of the book of Judges by putting its dominant trope out of joint. Urging every man to turn from the desires of his own eyes to the acknowledgment of his own sins, Mosiah wants everyone to develop anxiety for the whole. (p. 124)

He continues his analysis in detail over the following years in which Mosiah’s goal of avoiding chaos and conflict was almost immediately lost through the public rhetoric of Amlici and his followers, leading to a bloody civil war and lasting trouble for Nephite Society. The focus, then, is on Mosiah 29 to Alma 2, a short section surprisingly rich in lessons for our day. Gore sees, for example, an important contrast in the public rhetoric from Nehor and King Mosiah, a contrast between “two rival views of public life that are instantiated by two rival approaches to self-expression, being-in-and-for-oneself and being-with-and-for-others” (16). This is an important theme that Gore analyzes from many angles. A healthy society, where diversity in views can be flourish without bloodshed, requires a core of citizens with the commitment to not only seek their own agenda but to strive to understand one another and to seek the good of others. And this happens one soul at a time.

Mosiah called the condition of the people under judgeships “equality,” by which he meant equality of responsibility. One man alone was not responsible for the righteousness of the nation. Each man was responsible for himself.

The distribution and then the assumption of responsibility by the people is precisely what Mosiah hoped to accomplish with his new arrangement of affairs. (p. 119)

Gore recognizes the importance of restraining anger in our political discourse. Christ’s words against content in 3 Nephi 11:29 should be thoughtfully considered the next time we wish to shoud down a political opponent, not matter how irksome their views may seem at the moment. “Interested in keeping violence at bay, Mosiah knew, just as Samuel did, that contention and bloodshed over who should sit in the seat of power, once started, might never end. Mosiah taught his people to look forward to the awful reality of failed politics and to see unchecked passions — especially anger — as the root of all such failures” (pp. 39-40). Gore warns us the political power alone is not the solution to our problems, for it cannot deliver us from the problems of human nature. Something higher is needed, and this makes the Book of Mormon’s teachings vitally relevant to political discourse and to politics itself.

Of course, much depends on the kind of leaders that a society has. Gore stresses the importance of honorable politicians: “In this context I am using the word politician to describe one dedicated to the good of the whole group, one willing to place the common good above their own interests. Such a politician knows that friendship and good will are the foundation of political order and that only virtue and living speech—speech that is heartfelt, humane, loving, and just—can hold cities and peoples together” (p. 52). Hopelessly idealistic and futile? No more than the Lord’s call to “love thy neighbor.” Yes, hate may prevail today, but what else should we be seeking through al the days of our lives but charity, the most important gift of all?

Gore’s analysis recognizes the intriguing power blocks in Nephite culture that MOsiah and Alma had to deal with, including those with roots in the Mulekite culture and other outsiders aligned with the Nephites (p. 68). Considering analysis from Hugh Nibley on the lasting influence of old Jaredite culture, including the presence of Jaredite names like Nehor and Corianton among Nehite rebels, might have further strengthened his analysis. The pluralism of Nephite society in the era he focuses on is a fascinating issue and one worth considering with the aid of Gore’s analysis of political discourse and rhetoric.

There are many times when Gore extracts insights from the text that I had overlooked and which bring out some fascinating subtleties. The subtle and artful allusions to Gideon of the Old Testament while referencing the Book of Mormon’s Gideon and the valley named Gideon was one interesting example. Another occurs as he considers the great trust Mosiah showed in Alma as he conferred Nephite scriptures (brass and gold plates) and other sacred relics upon Alma, an unorthodox step in Nephite history given that Alma was not his successor to the throne:

Caretaking the plates was widely regarded as a sign of spiritual leadership among the Nephites, and the possession of the other artifacts would qualify Alma as a seer and signify that he had Mosiah’s blessing to rule. Mormon is careful to point out that this conferral of things on Alma happened before Mosiah engaged his people on the question of succession. It is tempting then to imagine that the outcome of Alma being chosen as the new chief judge was a foregone conclusion, which it may well have been. Yet the conferral of these things on Alma before engaging the people in the succession drama may well be indicative of the opposite. That he would need to confer the artifacts before engaging his people suggests the sincerity of that engagement and the possibility that the outcome could well have been otherwise than it turned out to be. In other words, the political engagement with the people might somehow have put the artifacts and records at risk if they were to be passed on according to the strictures of the new government, which may have conflicted in some way with what Mosiah regarded as his responsibility to care for the very things in question. (p. 76)

Much of Gore’s discussion of Alma the Younger and his background artfully leads us to lessons for today, including, for example, his treatment of idolatry in Alma’s early life and his opposition to idolatry later. Some readers of the Book of Mormon might see its condemnation of idolatry as irrelevant to our enlightened era. Gore again offers a valuable perspective:

Idolatry is, in rhetorical terms, an oversimplification of problems or an overconfident commitment to failed solutions. Idolatry grows out of and fosters idleness because it is rooted in promises that are simple to make but difficult to fulfill. It shifts the burden of deliverance to a person, object, or concept that does not have the power to deliver. Political idolatry is often connected to unbounded desire or the promise to be provided for on a lavish scale without any personal effort, and fundamentally it is a form of vanity. (p. 146)

Idolatry is a theme he addresses several times, opening our eyes to see that looking to political institutions and programs as the ultimate solution for any problem can be a form of idolatry. Offering infeasible political promises or demagoguery in general to gain popularity and power also goes beyond mere deception or irresponsible rhetoric and can be a form of idolatry (p. 147).

Throughout the text, Gore calls for us to listen better, to be willing to engage with opponents, to seek harmony and open discourse. A reader might wonder if more discourse and engagement was what Captain Moroni needed when faced with the uprising of the Kingmen in the middle of a dangerous war with outside enemies — and perhaps it was! I would be interested to see Gore’s analysis of issues later in the Book of Mormon, including Captain Moroni’s handling of civil discord, the collapse of the Nephite government as it split into tribes, and so on. If so, I look forward to his future treatment of these complex issues as well.

Some aspects of Gore’s treatment of the Book of Mormon left me wanting more. For example, as one intrigued by the emphasis on the workings and dangers of various “secret combinations” in the Book of Mormon text, I was disappointed that Gore did not have more to say, including how their interests and methods can also shape political discourse. Gore has very little to say of them, though, apart from the stating that Moroni’s cure for secret combinations to be found through examining our own hearts. There is more active guidance from Moroni on this issue in the Book of Ether, though of course, that section is outside the particular focus of Gore’s volume.

Some other Book of Mormon lessons, such as the danger of amassed power in the hands of one man, might also have been given more emphasis. For example, speaking of Mosiah’s epistle to his people about the proposed change in government, partly recorded in Mosiah 29, Gore writes: “While some remained unpersuaded by Mosiah’s epistle, the letter makes a genuine effort to teach readers to be wary of vicious conflict over who should rule and to promote in them responsibility for the community.” But why not also see it as a warning against assimilation of power in the hands of leaders?

Gore has an excellent discussion on the meaning of the term “the voice of the people” and its implications for us, especially our responsibility to be involved and fulfill our civic duty. Along the way, he makes an excellent point about a common mistake many readers make in thinking that the Book of Mormon is describing a political system like that known to Joseph Smith in the early United States:

The voice of the people is most commonly, and perhaps mistakenly, understood to suggest the establishment of a republican democracy, like that found in the United States. Many readers over the nineteen decades since the Book of Mormon’s emergence on the American scene have been tempted to read into Mosiah’s epistle similarities with the work of the American founders. A close reading, however, suggests as many differences as similarities between the book’s arguments and the goings-on of nineteenth-century American politics. Richard Bushman argues that the resemblance is more a tendency to see the past in terms of the present than a representation of the textual evidence.

The reign of the judges in the Book of Mormon bears little resemblance to nineteenth-century American republicanism. Nephite culture was never republican insofar as the Book of Mormon de- scribes government. The first prophet, Nephi, allowed himself to be made a king and established a line of kings that lasted 500 years. Around 92 B.C. King Mosiah gave up his throne and established a system of judges chosen by the voice of the people, but the re- sulting government was a far cry from the American pattern. The chief judge, by democratic standards, was more king than presi- dent, as suggested by the Book of Mormon phrase, “the reign of the judges.” After the first judge, whose name was Alma, was pro- claimed by the voice of the people, he enjoyed life tenure. When he chose to resign because of internal difficulties, he selected his own successor, who was the founder of a dynasty of judges. In the next succession the judgeship passed to the chief judge’s son and thence, according to his “right,” as the book says, to the successive sons of the judges. The “voice of the people” entered only marginally into the appointment of an officer who essentially enjoyed life tenure and hereditary succession.

Bushman is keen to point out the uniqueness of the Book of Mormon when read in the light of nineteenth-century American democracy. He emphasizes the significant differences between the Nephite polity and whatever political systems existed when the Book of Mormon was first published. Bushman observes that the voice of the people had only marginal influence on the Nephite polity. The regime established by Mosiah is not a democratic republic and does not seem to guarantee the separation of the lawmaker from the law enforcer. The voice of the people, whatever its political role was, never constituted pure majority rule. (pp. 117-8)

One theme in Gore’s book is our need for a wakeful, mournful attitude:

The gift of these texts, from Judges–Samuel to Ether and Mosiah–Alma, including especially Mosiah 29–Alma 2, is in the call to mourning and wakefulness. No other response can do justice to the horror and destruction brought about through sin. As bodies are devoured by wild beasts and bones are piled up like mounds of earth, the story reveals something sobering about the nature of being human. The strong, recurring desire to dominate others at the price of everything is precisely the opposite of the common good. Combatting this, finally, may not be totally within our power, but we can guard against it by cultivating mournfulness and wakefulness. (p. 195)

This is an important motif that Gore explores from several angles. In this world, there will be conflict and tragedy, but we can do our part to mitigate its impact. We have much to guard against, both in our own hearts and in external threats as well, hence the need to be alert, reflective, and wakeful. And there will be much to mourn. But the mourning leads us to change and a desire to help others in coping with their sorrows and needs:

The costs of failed politics is conflict that begins in indifference to the poor, the sick, and the weak but soon extends beyond them. Another choice is possible. The choice of living mournfully, shouldering the burden of the common good in a collective effort to realize equality, is always available and yields material abundance that is freely received and freely given, a prosperity that is both mutually beneficial and restful. (p. 189)

Gore urges us to accept the wisdom of the Book of Mormon, not to look to human political theories or parties as the ultimate answer for our challenges in society. It is wise advise, and Gore shows us there is much more to the Book of Mormon that we have realized when it comes to finding useful guidance in the fractious field of politics and political discourse.

Joseph Smith the Egyptian?

With the Book of Abraham being a recent fascination of mine, I was intrigued by Gore’s conclusion that recognizes a connection with ancient Egyptian wisdom in the Book of Mormon:

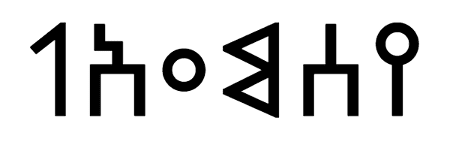

Some future account yet to be told will fashion Joseph Smith as an Egyptian and will seek out the Book of Mormon’s relationship to Egyptian culture and religion, sculpted and cast as it originally was in a reformed Egyptian tongue. That future account will have to reckon with the extent to which the rhetorical theology of the Book of Mormon invokes Egyptian metaphysics. What I have said here may serve as some preliminary notes toward that future work. The political theology of the Book of Mormon invokes the heart as the center of politics in keeping with Egyptian religious notions about the heart at the center of life, both personal and communal. The ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead contains the striking image of a person after death, having their heart weighed in a balance. Set on the opposite scale is a feather, a symbol of Ma’at, the goddess of truth and justice. Those whose hearts balance the feather perfectly enter into the way of life, while those, on the other hand, whose hearts are heavy with corruption and wrongdoing are de- voured by Ammit, the soul-eater: part lion, part hippopotamus, and part crocodile. The ritual judgment of weighing the heart is a profound image that, if applied to public discourse, has interesting ramifications. As a metaphor for what we most want in life and for what we feel most intensely, the heart has long been regarded as the locus of love, feeling, passion, compassion, and desire. At the center of our bodies, we imag- ine the heart to be centered on our treasure, beating the drum for what we most desire. It is appropriate that the heart was seen by the ancient Egyptians in terms of weight. We are either dragged down or uplifted by that which we desire, by that on which our hearts are set…. (p. 196)

Our inner knowledge only becomes serenity and peace when it generates the works of love, compassion, respect for life, sorrow for suffering, and the work of creating a new world. King Mosiah was channeling and Joseph Smith was translating Egyptian wisdom: the people must look to their hearts to uncover the best community. (p. 199)

There may be more to mine on the theme of ancient Egyptian wisdom in this context.

Overall, I feel that The Voice of the People is a valuable and reasonable book, even a pleasant surprise. I recommend it.

Thanks for this review.

I found Brother Gore's published testimony of the Book of Mormon quite moving:

https://www.fairmormon.org/testimonies/scholars/david-charles-gore

Maybe Gore addresses this question in The Voice of the People, but is there any reason to expect the Book of Mormon to provide any particular "guidance … about the fractious nature of modern politics"? Whether one sees it as an ancient historical text or a product of the 19th century, it seems a very odd place to look for such guidance. I know there's a tendency among believers of all kinds to think their own sacred texts are bottomless fonts of wisdom on every topic under the sun, but they're really not, at least not any more so than any other literary text. If one wants to understand and improve contemporary political discourse by analyzing the rhetoric of a narrative from the 1820s, one would be better off with a book like Last of the Mohicans or Hope Leslie.

I think this is borne out by the banality of so many of the generalities Jeff adduces in his review. To wit:

— Gore calls for us to listen better, to be willing to engage with opponents, to seek harmony and open discourse.

— Of course, much depends on the kind of leaders that a society has.

— … the danger of amassed power in the hands of one man.

Did we not know this already?

This passage strikes me as perhaps more substantial:

The choice of living mournfully, shouldering the burden of the common good in a collective effort to realize equality, is always available and yields material abundance that is freely received and freely given, a prosperity that is both mutually beneficial and restful.

Note, however, that this is not a statement about rhetoric. It seems to be a normative political statement against such philosophies as libertarianism, trickle-down economics, and "greed is good" capitalism. Is this statement true? Maybe, maybe not. (I happen to believe it is.) But its truth cannot be demonstrated by analyzing the political rhetoric of a book about ancient societies vastly different from our own.

Nothing against studying the rhetoric of the Book of Mormon. That seems worthy in its own right — and as a case study in religious rhetoric more generally, in understanding the strange history of Protestantism, and in all kinds of other ways. It just seems to me that if one is interested in understanding and improving the quality of our own politics, it makes more sense to look at actual examples from modern liberal democracies rather than theological texts from an earlier era.

— OK

Politics…..the church inserted itself into politics during the 2016 Presidential campaign. The leaders should have kept quiet. Showed their true colors. Anti Good.

The Washington Com-Post has an article by a former Ensign non-profit organization of the LDS church. David Nielsen says church is sitting on $100 billion dollars of tithing money and not using it for charity but using it for "for profit" endeavors.

Oops. Spell check got in the way.

A former employee of Ensign, a non profit org of LDS church. David Nielsen…

Three mission statements 1. Proclaim gospel 2. Redeem dead 3. Perfect saints

Transparent enough. Nothing about charity. James doesn't know what pure undefiled religion is.

Though members should be wondering why not make missions free of charge, funded out of tithing?