A popular attack on the Book of Mormon is the allegation of plagiarism, and a leading example cited by critics, including some who have left the Church, is 3 Nephi 20:23, where Christ cites the words of Moses from Deuteronomy 18:18-19, but actually seems to use language that is closer to Peter’s paraphrase of Moses in Acts 3:22-23 than it is to the Old Testament. “How can Christ be quoting a New Testament passage that hadn’t been written yet?”

Deut. 18:15, in warning those who would not hearken to the future prophet (Christ) that the Lord would raise up, the punishment in verse 19 is that the Lord “will require it of him.” But Acts 3:23 warns that the non-hearkeners “shall be destroyed from among the people,”which is much closer to 3 Nephi’s warning that such rebels “shall be cut off from among the people.” Sure, it seems like a case of clumsy and ignorant plagiarism.

Let me begin with a few observations. First, this is not a case of direct copying, because the Book of Mormon uses “cut off” rather than Peter’s “destroyed.” Second, the parallel to Acts 3 doesn’t only occur here in 3 Nephi 20. It occurs multiple times in the Book of Mormon. The same words from Moses are quoted in much the same way in 1 Nephi 22:20: “all those who will not hear that prophet shall be cut off from among the people.” That passage was written at a different stage in the Book of Mormon translation process, so if 3 Nephi 20 was just a sloppy blunder from Joseph the con-man and his vast team of research staff, zealously gleaning, checking, and applying information from many dozens of books and references materials to create a best-selling fraud that would wow and convert folks for many decades, then why was the same mistake made again in 1 Nephi 22? I mean, if you’re quoting Moses in a famous passage that every Bible student know in Deuteronomy 18, why open to a lesser known paraphrase in Acts 3 for the quote? And why make that blunder twice?

More than twice, actually. 3 Nephi 21:11 speaks of those who will reject the Gospel of Christ and warns that “it shall be done even as Moses said,” namely, “they shall be cut off from among my people who are of the covenant.” Not just having some “required of him,” but the more serious “cut off” from among the people, or in this case, “from among my people.” 3 Nephi 21:20 again warns that the rebellious shall be “cut off from among my people.” Now all these 3 Nephi passages could be lumped together and one could argue that Joseph just had that phrase in his head at the time and used it repeatedly during that day or week or writing. But how do we account for First Nephi passage that was probably widely separated in time from 3 Nephi’s translation? Didn’t it ever occur to him and his scholarly co-conspirators to look up Deuteronomy rather than Peter for a quote from Moses? Sloppy, sloppy, sloppy. And puzzling.

In fact, this is the kind of puzzle that ought to stir some thinking. The change in language from Peter and the persistent use of “cut off” in the Book of Mormon is not consistent with the sloppy plagiarism charge. So what is going on? Great question! Good questions with an open mind and some patience are often rewarded with interesting answers.

There’s a further question that students of the Bible might also wish to ask: “Why did Peter himself use language so different from Deuteronomy 18?” It turns out that Peter’s paraphrase does not follow the Septuagint in this case, so Peter appears to be departing from both the Greek and Hebrew texts. Why?

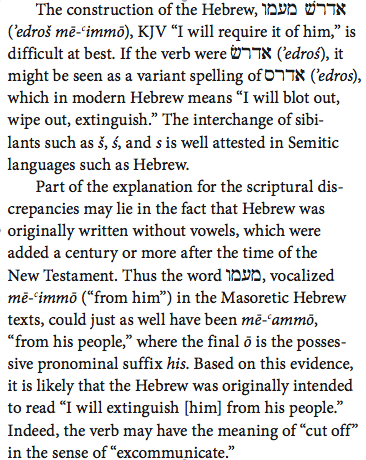

A possible answer to these questions, with interesting implications for the Book of Mormon, can be found in the Maxwell Institute’s publication, Insights, Vol. 27, No. 5 (PDF file), in the article on page 3, “The Prophet Like Moses” by John A. Tvedtnes and E. Jan Wilson. I recommend the PDF version to see the Hebrew more clearly, but an HTML version of the article is also available. There is a lot of detail in this short article, but here’s one passage with one of the main points:

Based on analysis of the Hebrew in Deut. 18 and several relevant passages elsewhere, a plausible case can be made that the original Hebrew may have read “cut off” instead of “require it” and referred to being cut off “from among the people” or “my people” instead of “of him.” Rather than both Peter and Joseph being sloppy in their quotations of Moses, there’s a reasonable case that Peter was informed by an ancient Hebrew source using language that differs slightly from the current Masoretic text, language that appears to be consistent with language uses consistently in the Book of Mormon. As for the Book of Mormon’s version of Deut. 18, are we dealing with a terribly sloppy but very lucky blunder by a con-man who inexplicably looked up and kept using Peter’s words when attempting to quote Moses, or are we dealing with an ancient text prepared by scribes whose version of Deuteronomy on the brass plates led them to understand Deut. 18 in much the same way that Peter did?

In light of intelligent questions coupled with scholarship, the way the Book of Mormon quotes Moses in Deuteronomy 18 is certainly interesting. What initially looks like a blunder upon further examination becomes an inexplicable blunder (“how could anyone be so stupid and sloppy?”), then a puzzle, and then an interesting find where a former weakness may actually be a strength. It’s a small thing and is certainly no reason to run off and join the Church, but it’s hardly a reason to leave.

I first learned about the passages in 3 Nephi and acts only a few months ago (something that was never covered in Seminary, Institute, or Sunday School, sigh). I had to learn about it from a random anti-Mormon site. (they always have great stuff. Great as in, nice bog long lists of everywhere in the Book of Mormon where it quotes the Bible. Great resource, if you can get past all their mindless accusations, and ironically, mutual plagiarism).

So a couple of months ago I did my own write up on these passages on my own blog, with a side-by-side comparison (if you want to check it out, click this link).

You're right, Jeff. It's a small thing and no reason to leave or join the Church, but Pauline phrases and other passages from the New Testament occurring at times verbatim throughout the Book of Mormon are a bit more difficult to get past. A neutral evaluator blinded to the title, provenance, and current status of the Book of Mormon might fairly conclude that its author or authors were dependent on the New Testament. That's fair, isn't it? It takes faith and other presuppositions to conclude otherwise. I don't accuse you or other apologists of ever denying that your position depends on faith and presuppositions, but often the apologetic method invokes the methodology of history and probabilities to make a point, and then facilely switches to a position of faith when the conclusion is no longer warranted by probability. Probability is favored when it bolsters a certain position, then ignored when it doesn't. Heads you win, tails I lose.

Roman, who are these deft apologists? The ones I read fully recognize that the Book of Mormon relies heavily on the KJV text and get into many other nitty gritty details in dealing with some of the concerns people have raised. I don't see the deft aversion of substance that you refer to. But yes, faith is always an element in our, um, faith. There will always be questions and objections and uncertainties. But we're glad to have some cool things to strengthen that faith at time.

Who are these facile apologists? All of them. It's due to the nature of religious apologetics. Anything is possible, but the historian seeks to demonstrate what is probable. The objects of religious faith are inherently improbable. Apologetics mixes appeals to probability with retreats to faith.

Apologists and critics seem to be converging. Apologists recognize that the Book of Mormon relies heavily on the KJV text. Great. How do they explain that? Joseph Smith used phrases from the King James to translate the Book of Mormon where possible. The problem is, how often should such a thing be possible? Here's an experiment for you. Without changing the meaning of their words, can you paraphrase Amos and Obadiah to sound like Paul? Another problem: various New Testament writers had distinctly different points of view. Not all gospel writers agreed about the divinity of Jesus. Not all New Testament writers agreed about the necessity of keeping the Torah. But in the Book of Mormon, different New Testament writers are quoted in such as way as to seamlessly harmonize all the points of view in the New Testament, as if they were all in agreement. Reasoning by analogy, the Book of Mormon paints an improbable picture of agreement among ancient writers and one harmonious theology between it and the Bible. How do you reconcile that?

"Not all gospel writers agreed about the divinity of Jesus."

Well, let's see, that would be four writers. Matthew is pretty clear that Jesus was not the son of Joseph. To me that suggests divinity. Mark talks about the resurrection of the Lord. That seems pretty divine to me. Luke quotes the Father telling Jesus, "Thou art my beloved Son; in thee I am well pleased." John tells us that Christ created all things – seems pretty divine to me.

So is this a hair-splitting exercise? Are we next going to discuss how many angels can dance on the head of a pin?

Our friend Roman here offers a rather circular argument. The general assertion is that Religious apologetics (Mormon apologetics in particular) ultimately retreat to the unprovable and the things that must be taken on faith. But if you look closely at what he is saying we see that he has defined religion is such a way that it can never be proven correct, or even have any salience to the facts of history.

He says that historians seek to demonstrate what is "probable", with the implication being that the most probable explanation being the non-religious one. Then he defines the "objects of religious faith" as those things that are improbable. This is currently a very popular argument and I have seen this argument in many different forms but essentially is boils down to this:

(P) Religion deals with things that are inherently unprovable and cannot not be historically (or scientifically, choose your favorite word here) proven.

(C) Therefore any argument for religion is inherently unfounded and cannot be proven because religion (from our premise) consists of all things that cannot be proven.

The problem is that this is a circular argument as people like Roman first assume that any Religious apologetics must retreat to a basis of faith (where faith is defined as things that can never be proven), then say that any apologetic argument is unfounded because it relies on an unprovable faith.

But this argument doesn't work if you don't assume that the objects of religious faith are things that are inherently unprovable or even improbable.

[As a final note, I should point out that certain strands of religious sentiment are not free from this same logical fallacy. This is why I have very little regard for Kierkegaard and generally place him in the same category as Nietzsche. Both have perhaps done more to destroy religion than almost anyone else in the past 200 years. I would explain why I say that except this is not my blog and it would take several posts just to explain why I feel that way.]

Anonymous,

Mark doesn't claim that Jesus is God. See Mark 10:18. Resurrection doesn't make one God or a god. Remember the resurrection of the unjust? There was an early view among Christians called adoptionism, where Jesus was believed to be the adopted son of God. This view is expressed in an older Greek manuscript of Luke where Jesus is adopted at his baptism. Being called the "Son of God" didn't necessarily make one God or a god in the worldview of the Jews or Mediterranean pagans. Israel was called God's son, and stoic philosophers said that we are children of God. Only John uses the phrase "only begotten." You're right that some gospel writers thought that Jesus was divine. Hence the disagreement.

Quantumleap,

I appreciate your thoughtful engagement. You're right about my argument depending on a definition, but I disagree that it's circular. I'm not arguing that the premise follows from the conclusion. My conclusion is simply that apologetic arguments suffer from confirmation bias because demonstrably improbable belief claims are relegated to objects of faith rather than accepted as disconfirmatory. It's a system where only positive hits count.

My assertion that objects of religious faith are improbable is based on the idea that if something is believable because it is supported by objective evidence, then religious faith is not required. The faith is dormant, to borrow a phrase from the Book of Mormon. The various faith claims that distinguish one religion from another cannot be supported by objective evidence. That which can be demonstrated is generally agreed upon by people of different faiths.

I guess I would put money on Mark and Luke believing that Jesus was/is divine. To infer that they didn't because some key word is missing in the extant translations of their writing seems quite the stretch.

(A man is crucified and is clearly dead. On the third day from his crucifixion he rises from the dead, ascends into heaven, and is seen on the right hand of God. Not divine? Whatever…)

(Gabriel tells Mary that she will bear the Son of God. Not divine? Go figure…)

I know. It's difficult to get past your presuppositions. Does Paul mean to say that the resurrected unjust will be divine, because they are resurrected (Acts 24:15)? If Jesus is divine, why does not the description of good apply to him as it does to God (Mark 10:18)? You can't see that not all scripture writers believed the same things. You're stuck with the worldview that you inherited.

No need to go all ad hominem.

Christ resurrected himself by his own power. To date, no unjust person has been resurrected by any power. No other person who has been resurrected has been resurrected by their own power. That's a significant difference.

More like ad Anonym, but I won't do that either 🙂

To my knowledge, Mark never says that Jesus resurrected himself by his own power. Interestingly, Paul and other New Testament epistle writers say repeatedly and explicitly that God raised Jesus from the dead (1Cor 15:15; 6:14; 2Cor 4:14; Rom 8:11; 10:9; 2Tim 2:8; 1Peter 1:21; 1Thes 1:10; Acts 3:15; 5:30; Acts 13:30). So the idea that Jesus raised himself from the dead isn't supported by most New Testament writers. You could infer it from John's writings, but John has a higher Christology than just about anybody else. Even Matthew and Luke use "raised" from the dead in the passive voice.