Students of biblical literature and of the Book of Mormon can now access an important new volume on chiasmus, Chiasmus: The State of the Art, just published as a special supplement to the journal BYU Studies Quarterly. For subscribers (or everyone?), the PDF of the entire edition can be downloaded or individual articles can be viewed as HTML or PDF files.

Today I’d like to discuss an excellent article by Dr. David Rolph Seely, “‘With strong hand and with outstretched arm’ (Deuteronomy 4:34); ‘With outstretched hand and with strong arm’ (Jeremiah 21:5): Chiasmus in Deuteronomy and Jeremiah” from pages 129 to 150. He discusses four different kinds of chiasmus that are shared in Deuteronomy and Jeremiah, and also compares these types to what he sees in the Book of Mormon. Here is an excerpt:

Four Kinds of Distinctive Chiasmus in Deuteronomy and Jeremiah

Various scholars have identified four distinctive forms of chiasmus in Deuteronomy that may have provided a rhetorical prototype for Jeremiah. This does not necessarily mean that these forms of chiasmus are unique to Deuteronomy and Jeremiah but that they are suggestive of Deuteronomy providing a prototype for similar figures in Jeremiah. It could be argued that these four distinctive forms of chiasmus are representative of seventh-century Judahite rhetorical tradition. The four distinctive forms are:

- Chiasmus of Speaker

- Chiasmus in the Position of Completing a Unit of Text

- Chiasmus Where Particles Create Semi-chiasmus in the Middle Two Cola of Four Cola Units

- Chiasmus Where Rhetorical Questions Occur in the Middle of the Structure

After examining these, Seely also considers examples of chiasmus in the Book of Mormon and shows that all but the first form are present in the Book of Mormon. Below I will tentatively propose that one famous chiasmus in the Book of Mormon may also share features of that first form, chiasmus of the speaker.

Here is what Dr. Seely writes on this category of chiasmus:

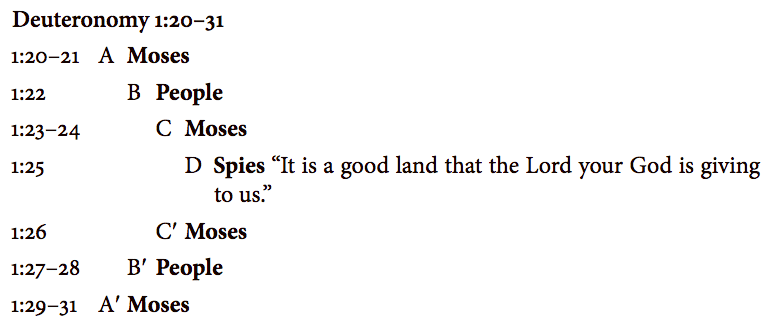

1. Chiasmus of Speaker: A distinctive form of chiasmus in Deuteronomy is the chiasmus of speaker. This means that the inversion in the chiasmus is not with the themes or the keywords of the passage, but rather with the speakers. Deuteronomy 1:20–31 illustrates a chiasmus of speakers. This type of chiasmus was first noted by Lohfink in 1960 and later discussed by Moran. Lundbom describes this chiastic structure as follows: “In Deut. 1:20–31, Moses narrates in the first person, introducing the direct address of each of the participants in the discussion—including himself—in chiastic fashion.”

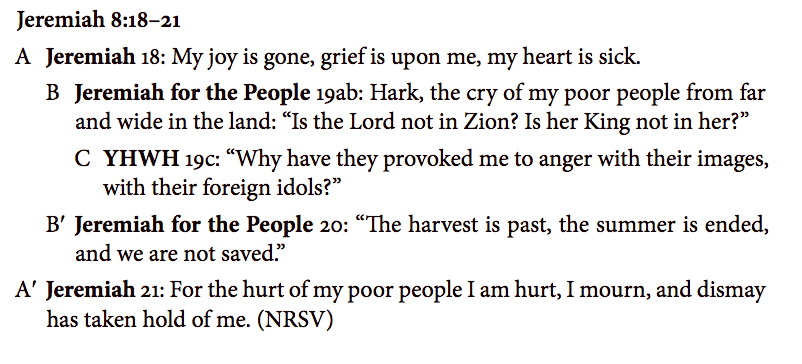

The same rhetorical figure of chiasmus of speaker is found in Jer 8:18–21. In this passage Jeremiah speaks first (v. 8) and then he speaks on behalf of the people (v. 19ab). In the center of the chiasmus, Yahweh speaks (v. 19c), then Jeremiah speaks again on behalf of the people (v. 20), and finally Jeremiah concludes (v. 21).

Another example of chiasmus of speaker is found in Jer 5:1–8 where the chiasmus alternates between the words of Yahweh to the search party and Jeremiah, of Jeremiah to Yahweh, and then of Jeremiah to himself. It begins and ends with the words of Yahweh to the search party (vv. 1–2 // 7–8). The second and fourth speaker is Jeremiah speaking to Yahweh (vv. 3 // 5c–6) and in the center Jeremiah speaks to himself (4–5b).

Later, as Dr. Seely explores the presence of related forms of chiasmus in the Book of Mormon, he presents good examples for three of the four types but not really for the chiasmus of the speaker:

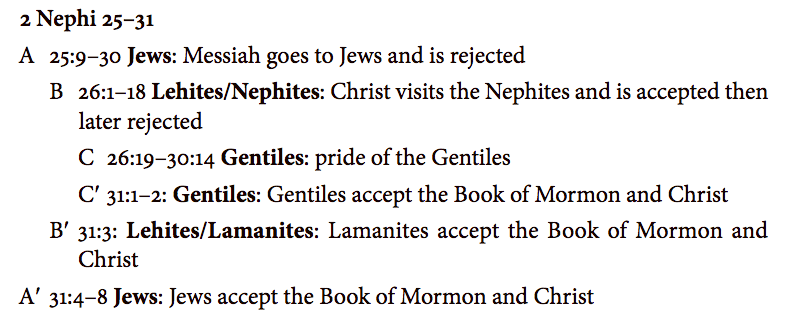

While I have not yet located an example of a chiasmus of speaker in the Book of Mormon, we can point to a similar example involving the reversal of the subjects in the text. In Nephi’s interpretation of the block of Isaiah chapters that he has inserted into his record in 2 Nephi 12–24 that equal Isa 2–14, he gives a long historical discussion of how these Isaiah passages may help illuminate the history of the Jews, the Lehites, and the Gentiles. Nephi presents this discussion in a chiastic form—that also turns out to coincide with the historical order of the visit of the Savior to the three peoples and their acceptance of the Book of Mormon:

I find that interesting. But there may be yet another example to consider, one that may come closer to the chiasmus of the speaker form found in Deuteronomy and Jeremiah. Consider Alma 36, where Alma is narrating a sacred experience to his son, Helaman. Technically, everything being said is simply Alma speaking to his son, but in this discourse, he recalls or remembers the words of various parties (his own, his fathers, his father Alma, his father Lehi, the words of an angel, the ministering of the Spirit, and the answer to his plea unto Christ–the latter two, of course, do not involve explicit spoken words, but can be viewed as acts of communication and ministering). There are multiple speakers or “living sources” here with with recipients of communication, whether explicit or implicit.

The structure could be mapped as:

A. Alma urges Helaman to give ear to his words and keep the commandments (v. 1) [source: Alma’s words]

B. Alma reminds Helaman of the story of their fathers (“our fathers”) and their deliverance (vv. 1-3) [source: “our fathers”]

C. Alms shares his own testimony and story with Helaman, urging him to hear his words and learn that he might be blessed (vv. 3-5) [source: Alma’s words]

D. As he sought to destroy the Church of God [by speaking to other against it] (v. 6), an angel descended and spoke to Alma and his brethren, causing Alma to fall and lose strength (vv. 6-11) [source: an angel]

E. Alma, in torment over what he had done (vv. 12-16), recalls the words of his father (“my father”) about Christ (v. 17) [source: Alma’s father]

F. Alma cries out to Christ, the Son of God (v. 18) [source: Alma, speaking to Christ]

F’. Christ answers Alma with forgiveness and joy (vv. 19-20) [source: Christ answering Alma]

E’. Filled with exquisite joy, Alma sees what Lehi (“our father Lehi”) had written, describing what he saw in the heavenly court (vv. 21-22) [source: “our father Lehi”]

D’. Alma regains his strength and stands, is filled with the Holy Ghost, and speaks to others to build up the Church (vv. 23-25) [source: the Holy Ghost]

C’. Alma testifies that the word imparted to him has blessed many and has blessed him (vv. 26-27) [source: Alma’s words]

B’. Alma appeals to the deliverance of their fathers (“our fathers”) from captivity (vv. 28-29) [source: “our fathers”]

A’. Alma urges Helaman to keep the commandments to be redeemed. “Now this is according to his word.” (v. 30) [source: Alma’s words]

If we view the text with a lens of the source being cited or referred to and the directionality of communication (including ministering), rather than just key words and concepts, it does seem to divide into sections with a chiastic structure of its own. But some of this structure does rely on repeated concepts or keywords, so it’s not entirely based on implied or explicit sources. It could be simplified to something like this:

A. Alma speaks to his son, citing the deliverance of their fathers

B. Alma recounts his “anti-ministery” to destroy the Church

C. An angel descends and speaks to Alma

D. In torment, Alma recalls the words

of his father (“my father”) about Christ

E. Alma cries out to Christ, the Son of God

E’. Christ implicitly answers Alma with forgiveness and joy

D’. Alma sees what Lehi (“our father Lehi”) had seen in the heavenly court

C’. Alma is filled with the Holy Ghost

B’. Alma recounts his ministry to others to build up the Church.

A’.

Alma speaks to Helaman, citing the deliverance of their fathers.

There is certainly some poetic license being used here, but does that exceed the bounds of what might have been intended in the poetry itself by an author familiar with Hebraic rhetorical forms such as chiasmus? In other words, could this be viewed as a form of a chiasmus of the speaker? I’m not sure but welcome feedback.

The references to fathers is interesting. Referring to Lehi as “our father Lehi” does strike me as a potentially deliberate device to link his and Lehi’s vision of God and the heavenly court to his own father’s prophecies of the coming of Christ, the Son of God. The tight relationship between the visitation of the angel and his loss of strength and the visitation of the Holy Ghost and his regaining of strength and arising seems to link the ministering of the Spirit to the words of the angel in this parsing of the chiasmus, in spite of the Spirit not using words in filling and fortifying him.

Alma 36 is a complex chiasm, not just because it has many steps in its fully mapped structures based on related words and themes, but because in the “messy” parts there is actually a lot of structure that seems to call out for additional lenses to be viewed, like the chiasmus of the speaker lens. This may be related to some concepts I once explored in the article, “‘Arise from the Dust’: Insights from Dust-Related Themes in the Book of Mormon (Part 3: Dusting Off a Famous Chiasmus, Alma 36),” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 22 (2016): 295-318. Speculative, yes, but I think there is more artistry to Alma 36 than anyone simply reading the English translation would have ever noticed until scholars began teaching us about the rhetorical and poetical devices of the ancient Hebrews, which we can still be seem shining through the translation process.

Fascinating exploration of a well-known chiasmus with a narrow view applied against it. I liked it and think you're on to something. Very nicely done!

Maybe, Jeff, but it seems a bit of a stretch, and in any event I'm not sure what the significance would be since there's nothing particularly magical about chiasmus.

For what it's worth, there's a kind of "chiasmus of the speaker" in Frankenstein (1818) that stems naturally from its structure as an epistolary novel:

A. Robert Walton speaks to his sister Margaret Saville

B. Victor Frankenstein speaks to Walton

C. The monster speaks to Frankenstein

D. The cottagers speak to the monster

C.' The monster speaks to Frankenstein

B.' Frankenstein speaks to Walton

A.' Walton speaks to Saville

One could argue that there's one more layer of narration, in which Saville (as a stand-in for Shelley herself) is speaking to us as readers.

Something similar happens in many other epistolary novels, as well as what we call "frame stories" (e.g., Titanic).

— OK