I’m nearly finished with Dan Vogel’s book, Book of Abraham Apologetics: A Review and Critique (Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Books, 2021). It’s a fascinating read for those seeking to understand the best, most refined arguments that can be hurled at the Book of Abraham. Vogel seeks to offer a comprehensive analysis of the issues and the failure of LDS scholars and defenders of the faith to account for the evidence that Joseph Smith committed fraud in claiming he was translating an ancient text.

Vogel’s paradigm on the translation of the Book of Abraham involves a couple of important claims:

1) Joseph’s “translation” method began with attempting to create an “alphabet” and grammar as guides for translating Egyptian characters into English, though the real point of these exercises in 1835 was probably just trying to impress his peers and brainstorming to come up with story lines for the final story that he would dictate. The Egyptian Alphabets came first, then the Grammar and Alphabet of the Egyptian Language, all attributed to Joseph Smith as the mastermind, and then came the dictation of the “translation” of Abraham 1 to Abraham 2:18. Dictation of the rest of the text and elucidation of Facsimiles 2 and 3 came later, much of it in 1842 in Nauvoo.

2) A key window into Joseph’s translation comes from the Book of Abraham manuscripts that have a few Egyptian characters on the left margins and large blocks of English text to the right, showing that Joseph was “translating” impossibly large amounts of text from individual characters. This also shows that the source of the Book of Abraham was certainly a papyrus fragment known as JSP XI, which contains nearly all the characters on the Book of Abraham manuscripts, leaving no room for a “missing scroll” theory. Critically, two of the Book of Abraham manuscripts have some identical scribal corrections showing that they were created simultaneously in a session with Joseph Smith dictating the translation live.

A detailed timeline is provided which jives well, of course, with Vogel’s paradigm and with several key dates from Joseph’s journal. Everything seems to fit.

As a result, Vogel believes he has shown that we now know exactly what Joseph claimed to be translating and we can see that it has nothing to do with Abraham and shows Joseph’s complete failure to understand anything about language and translation. Joseph has been caught and exposed. Vogel also undermines the arguments of LDS apologists, attacking the “missing scroll theory,” the claim that the Kirtland Egyptian Papers represent efforts at a “reverse translation” (i.e., decoding Egyptian using the inspired translation as the key to developing an alphabet), attempts by Nibley and others to blame the bizarre Kirtland Egyptian Papers on the work of Joseph’s scribes rather than a “revealed” product from Joseph, and even showing that some of the purported evidences for antiquity in the Book of Abraham don’t hold up or could have been based on information known in Joseph’s day.

All told, it’s an excellent example of a comprehensive hard-hitting attack on the Book of Abraham and those who support it, using arguments that Vogel and his fellow critics have honed over decades of zealous exploration. It’s a book that is definitely important in the debate on the origins and value of the Book of Abraham. Vogel creates a compelling and plausible paradigm for rejecting the Book of Abraham that appears to be sound and scholarly–until you look at the historical data and many relevant documents and notice what’s missing.

So much is missing! Most readers won’t know that, of course, but for those who have engaged with Vogel on Book of Abraham issues and know that important issues have been raised and pointed out to him or discussed in references he’s cited or responded to in the past, we might expect that this book, which touts Vogel’s objective exploration “based entirely in a dispassionate, balanced analysis of the relevant historical documents” (p. 13), should at least acknowledge issues that seem to challenge his theory. OK, he can’t deal with everything, and perhaps many arguments from the defenders of the Book of Abraham seem unworthy of Vogel’s attention, but in my opinion, in too many cases, especially when there’s not an easy way to nitpick the evidence or the argument, the issue is simply absent in this work.

[CORRECTION, 3/26/2021: When I posted a little earlier today, I initially pointed to an apparent missing line in Frederick’s document, based on the transcript on the JSP website and also the final transcript in the JSP publication, but after I looked closely at the photograph, I realized that this was a painful glitch in the transcript. Both transcripts, from website and the book, are missing an entire line that makes it seem like Williams has skipped a line, which I read as a haplography from copying. Oops! Snagged by an error in the JSP volume on the Book of Abraham. Sorry for the blunder! What I thought was a smoking gun haplography, a classic copying error, actually was, but from the wrong century. I will strive to better check the photographs, though they are faint and hard to read, in future interactions with unexpected items in the transcript.]

The Twin Manuscripts

I would say the single most important argument used by Vogel and other critics to attack the translation of the Book of Abraham by Joseph Smith is the evidence of simultaneous dictation in two Book of Abraham manuscripts, termed by the Joseph Smith Papers Project as Book of Abraham Manuscript A written by Frederick G. Williams and Book of Abraham Manuscript B written by Warren Parrish. These are supposedly being written at the same time as Joseph carefully dictates the “translation” of the “Egyptian” characters (a few are made up) in the margins.

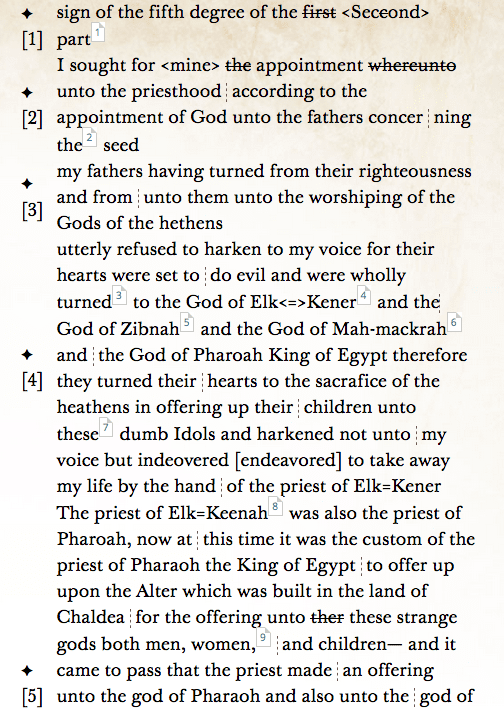

Below I show the transcript of the first page of Manuscript A as shown on the Joseph Smith Papers website. This transcript is not the final version — for that you need to refer to the printed edition, volume 4 of the Revelations and Translations series, Book of Abraham and Related Manuscripts, ed. Robin Jensen and Brian Hauglid (Salt Lake City, UT: Church Historian’s Press, 2018), which I abbreviate as JSPRT4. (I’ll point out any differences that matter–the website’s transcription is usually the same as the printed version, but doesn’t make it clear when insertions are above the line or added some other way.)

(Just to the left of the paragraph marker “[3]” is “and from | unto them unto …” which looks like a line is missing — and it is, but only from the transcripts, not the original document.)

You can see a variety of errors and corrections in the printed and online transcripts that are made easy to see in the transcript, when they aren’t missing, that is. (Be aware that there may be other mistakes in the transcription, such as in the fourth line from the bottom where “ther” occurs followed by “these.” Examination of the photograph show that “them” was written initially, and then altered to “these,” as John Gee has noted. The printed transcript in the JSP volume is closer, still claiming that “ther” came first before altering it to “these.” Comparing the overwritten final letter to the letter “m” elsewhere on this page should make it clear that “them” is likely the word that was first written.)

In fact, there are many scribal errors or errors and corrections in the manuscripts and subtle differences between these two manuscripts that don’t fit the theory Vogel proposes. John Gee has summarized his findings after examining all the differences and changes in these twin manuscripts. See his excellent “Fantasy and Reality in the Translation of the Book of Abraham,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 42 (2021): 127-170, published in January this year but perhaps not in time for Vogel to respond to it in time for the March release of his book. Gee offers important points about what we can learn from the details of these manuscripts that make it difficult to see much hope for Vogel’s theory, especially when we consider his other January publication that strikes at the historical data related to Vogel’s timeline and overall paradigm. See John Gee, “Prolegomena to a Study of the Egyptian Alphabet Documents in the Joseph Smith Papers,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 42 (2021): 77-98.

Vogel doesn’t consider the various issues that seem to point to visual copying of (or reading from) an existing manuscript, where it can be easy to jump to the wrong word or to where cursive words can be easily misread. An example of the latter is the error both scribes make in first writing “regular” and then striking it out and writing the correction: “royal” in the phrase “one of the royal descent.” I was puzzled when I first saw this correction until I examined the cursive writing in this and other parts of the Joseph Smith Papers and saw that the letter “e” can often look like an “o”, the letter “y” can look like a “g”, and “a” can look like a “u”, making it not just possible but even perhaps easy to look at “royal” in cursive writing from that era and see the letters “regul” as if the word “regular” were meant. A scribe copying from an existing text or somebody reading to the scribes from an existing text could lead to this error.

Vogel primarily focuses on a couple of items that do support his theory. Especially important is what is almost always cited as iron-clad proof of oral dictation to two scribes simultaneously: the errors and corrections made in the first two lines.

It’s easy to see how Vogel’s theory would work for these lines:

Joseph dictates the strange heading and changes his mind on the spot. “Sign of the fifth degree of the first –wait, let’s make this the second, so please write ‘second part.'” The scribes then cross out “first” and both insert “second” above the line. Joseph continues: “I sought for the appointment — [pause] wait, change that to ‘mine appointment.'” The scribes, now having already written “the appointment,” strike out “the” and insert “mine” above the line. Joseph continues: “Whereunto — [pause] no, strike that. It’s just ‘unto.'” The scribes strike “whereunto” and write “unto” in line, along with the subsequent dictation of “Priesthood according to the appointment of God unto the fathers….”

That could certainly account for those lines. But there are some unanswered and certainly unasked questions in Vogel’s treatment.

First, if the purpose of this session is to create new revelation, a new translated text, why does Joseph give it such a strange title? The first line begins with a non-Egyptian character and the heading “Sign of the fifth degree of the second part.” That’s the kind of heading or title one would expect if this work session was aimed at more exploration and brainstorming to flesh out the incomplete GAEL that is broken up by degrees and parts, and did not yet have entries for the characters being considered in the margins on these Book of Abraham manuscripts. There’s a strong argument to be made that these manuscripts were part of an attempt to expand W.W. Phelp’s incomplete GAEL by trying to find ways to relate more characters to existing translated text, rather than creation of the original translation.

Second, why do insertions above a line require dictation at all? The text may have been labeled as intended for the “second part” for any period of time before the error was noticed and the writers made that correction. Somebody may have changed their mind or noticed an error relative to an existing manuscript or received instructions from someone else requiring the change, and then acted to correct that error. It could have happened right away or many minutes later, perhaps after they thought their work was complete. But an error corrected with an insertion does not require Joseph’s live dictation. The inline corrections tell us more about what happened when, of course.

Third, if this is live translation, why do the errors in Abraham 1:4 that need to be corrected sound a little strange in the context of orally dictating a story? I can imagine Joseph saying “my appointment” and then changing it to the more KJV-like “mine appointment,” but why would an author speaking a text in Abraham’s voice miss the natural determiner (“my” or “mine”) that is needed here and instead just say “the appointment”? After “appointment” is spoken, it’s pretty obvious that it needs to be followed with something like “unto,” so how does “whereunto” become spoken instead?

What’s curious is that both of these mistakes may make more sense if an existing manuscript were being used that also had at least the previous verse Abraham 1:2, but here with Abraham 1:3 being the beginning point for these new copies, perhaps to augment the work that W.W. Phelps already had in his Book of Abraham Manuscript C with the text of Abraham 1:1-3 and some characters linked to specific words in the text. The use of an existing manuscript being read aloud to the copiers or being viewed by one of these copiers could help explain the errors.

“I sought for mine appointment unto” in Abraham 1:4 is related to a phase in Abraham 1:2: “I sought for … the right whereunto.” Someone who had just read or scanned vs. 2 might have the concept of “I sought …whereunto” in his head, leading to accidentally saying “whereunto” again in reading vs. 3. Likewise, vs. 4 itself has “appointment” twice, initially with “mine appointment” but soon followed by “the appointment.” Someone who had just read or scanned the text could easily have noticed the other “appointment” with “the” and not “mine” and then read “the appointment” by mistake. These errors may suggest use of an existing document.

The evidence in the manuscripts does not require someone reading an existing text to the scribes, though I have favored that theory in the past with the proposal, based on clues from spelling and a major dittography, that Parrish was reading aloud to help Williams make a copy at the same time Parrish was preparing his own copy–but the possibility of simultaneous copying from an existing manuscript possibly being read aloud might still be a possibility to consider. Such errors could easily happen for a scribe visually copying an existing text, having already seen “whereunto” above and writing it instead of “unto,” and seeing “the” before appointment in vs. 4 and making a related mistake. Reading aloud or copying errors could both account for this. But how could inline copying error of “whereunto” being changed to “unto” occur with both scribes? There are two possibilities.

One explanation favored by John Gee is that Parrish was copying Williams’s document and deliberately preserving the details of the manuscript, warts and all. Gee offers supporting evidence in observing that Parrish preserved some of his own obvious errors when he copied his manuscript onto Manuscript C. Another possibility is is that they were both striving to make a detailed, exact copy of an original with its own errors and corrections, choosing to preserve original errors and corrections for some reason (maybe out of respect to the original or perhaps they were instructed to just make a fully accurate copy). Whatever the cause, this scenario of identical errors and corrections does not occur frequently in these manuscripts, while there are numerous errors and corrections that readily fit into scenarios without dictation from Joseph Smith and none that clearly require it.

Even if dictation had to be the cause of the first couple or errors, that doesn’t tell us who was dictating, Was it Joseph speaking new revelation, or a friend reading from an existing manuscript, or Parrish himself reading from a copy as he and Williams worked together to make their own duplicates?

John Gee’s summary of the dozens of issues to consider in these two texts suggests that nearly all can be accounted for by having Williams copying from an existing manuscript, followed by Parrish copying and correcting Williams’s text. And none require Joseph to be giving live dictation.

[Here I also wondered how Gee’s view could be squared with the missing line I thought was present because of the error in the JSP transcription, but noticed later that there was no missing line on the hard-to-read photograph in the JSP volume. Gee’s approach still works!]

I am beginning to like Gee’s view here, and am less fond of my prior proposal that the two scribes were working together, but Parrish being the one who could best see the manuscript they were copying, and possibly reading it aloud, at least initially, for the benefit of Williams. In that view, when Parrish left early, Williams then continued copying from the existing manuscript and made a major dittography as he copied a large block of text a second time without realizing — something impossible in oral dictation. Gee’s view seems simpler.

The portion of Phelps’s document in his handwriting (Abraham 1:1-3) may have been based on the original dictation of Joseph Smith, later amended with Phelps’s notes on possibly related characters, or it may have been copied from the first page of Joseph’s dictated Book of Abraham translation. It bears a suitable title from or for such an official manuscript. If Phelps needed help for whatever the GAEL project was, it would make sense that his helpers would begin with the verse following what Phelps already had. It also makes sense that they would not need to recopy the title, but would give their documents a header that refers to their objective: fleshing out definitions in a particular section (fifth degree, second part) of the GAEL with characters that were not yet (and never would be) in that bound but unfinished work. Viewing these manuscripts as tools being used by Phelps and some interested helpers to strengthen the enigmatic GAEL makes sense in light of these and other clues. That would be an exercise using existing translation of the Book of Abraham, not creating the translation.

There’s much more missing in Vogel’s work, including some of the most fundamental questions that should have been considered, as well as a puzzling neglect of some of the most important responses to the critics’ theories. We’ll consider that in my next post.