This is somewhat embarrassing, but it’s best I come clean now. I made a serious mistake in a previous post, “Burying Nahom,” when I said that it would be unlikely for Joseph to have traveled 50 miles from Harmony, Pennsylvania to the academic Bountiful of his region, Allegheny College and its amazing library. If he was actually able to frequent that library, it could have helped him find the word Nehem in Arabia enhance a verse or two, and the collection of books there could have helped on a variety of minor details in Joseph’s relentless quest to give us tantalizing evidences that wouldn’t be noticed for over a century. But as I said, I erred when I rashly argued that the 50 mile journey was just too far to be practical for him. I stand corrected–my apologies!

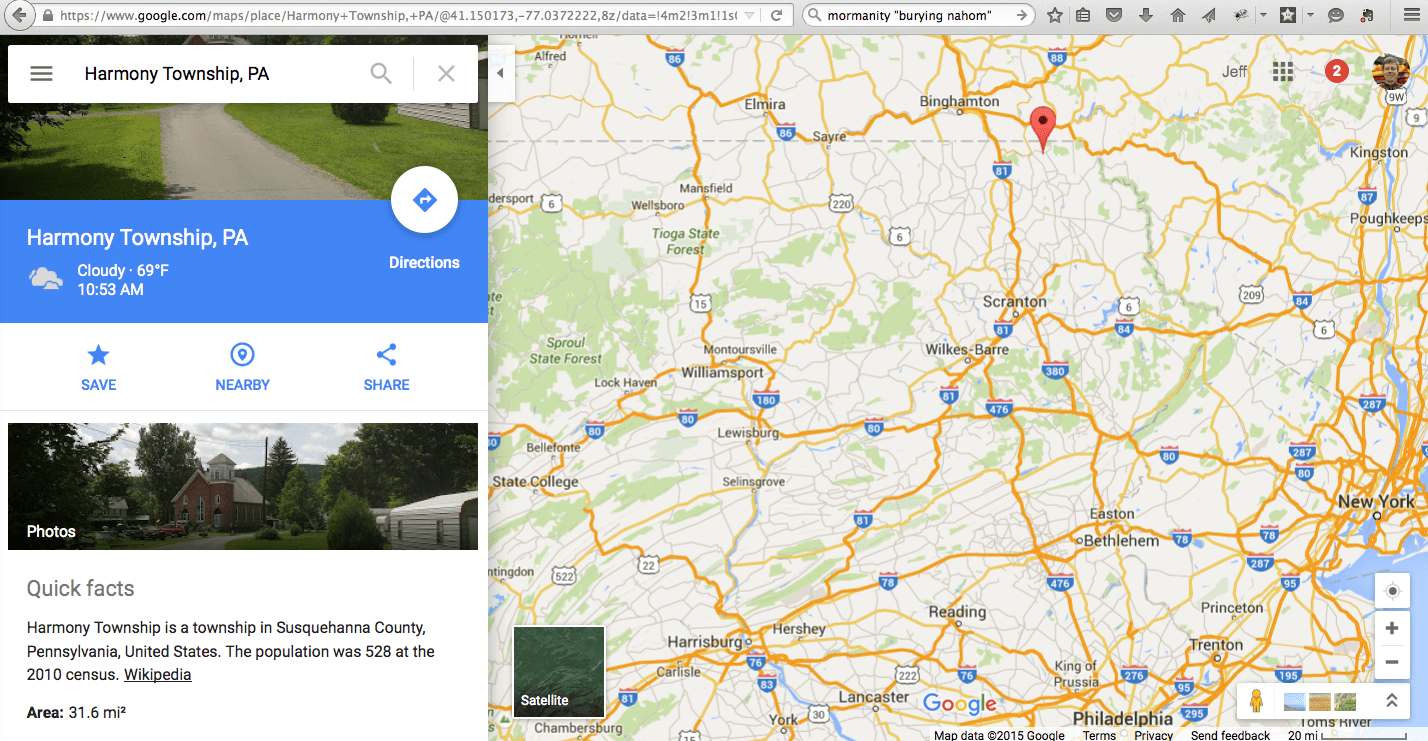

While Allegheny College is 50 miles away from Harmony, Pennsylvania, that town isn’t the Harmony where Joseph was translating the Book of Mormon. That was Harmony Township, Susquehanna County, Pennsylvania, which you can find by entering “Harmony Township, Susquehanna, PA” into Google Maps. You can also see that Joseph’s Harmony Township is actually around 320 miles from Allegheny College. Ouch. I was off by a factor of six. It’s closer to the medical library in Philadelphia which also had a book with a map of Arabia in it showing Nehem, but still way too far. (Click to enlarge.)

Kudos to the good folks at FAIRMormon.org for their helpful information (way down on that page) that exposed my blunder. Painful as it is, I have to give them credit and admit my mistake. 320 miles, not 50. So sorry!

For those who think they have a reasonable theory for how Joseph fabricated the Book of Mormon, if he did it with books and maps, it remains a mystery where and how he got them and, more crucially, how he could have used them to dictate the text we have.

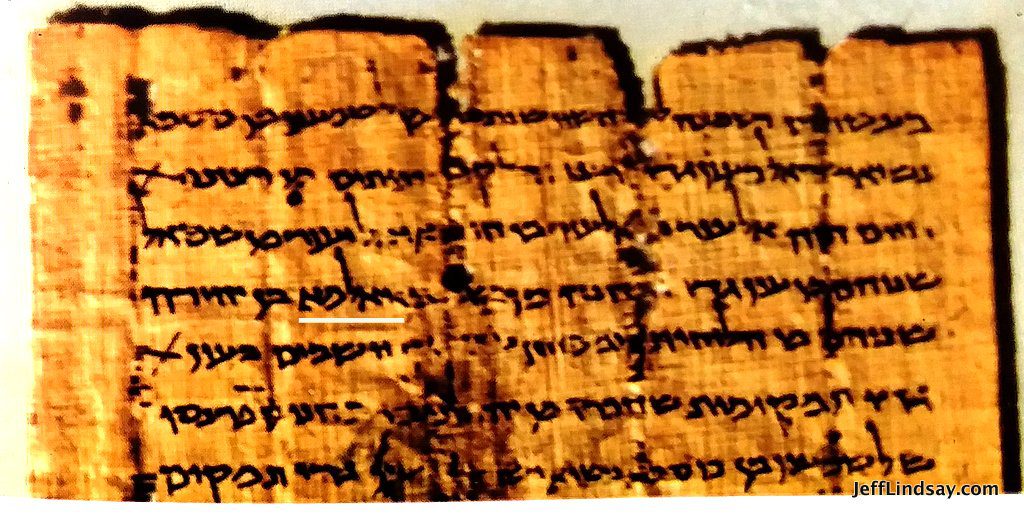

As a reminder, the Arabian Peninsula evidence, as explained on my Book of Mormon Evidences pages, is about much more than just a lucky hit with the name Nahom. Nahom alone is cool, I’ll admit, being in the right place (right where you can turn due east off the ancient incense trails), and being an ancient burial place, and having archaeological evidence that the tribe with a related NHM name was in the region in Lehi’s day–not to mention the appropriate Hebrew word play that Nephi appears to have made, linking Nahom to mourning and murmuring. Oh, and did I say that if you go east from Nahom, you can in fact reach an excellent candidate (or two candidates) for the previously-alleged-to-be-impossible place Bountiful on the coast of Oman, which, in light of the extensive field work done there verifying the plausibility of the leading candidate (and some decent arguments for the plausibility of the runner-up), is now, of course, deemed to have been obvious and easily done by just, say, glancing at map of Arabia, which Joseph simply and obviously must have had access to?

But what could Joseph have gleaned from the best and most relevant Nehem/Nahom/Nehhm-containing map of his era, even if he did manage to steal off to a distant library, or if one came “nearby” as it floated along the Erie Canal (as some have suggested might have happened), which wasn’t very close to Harmony, either? Could he have come up with Shazer? The Valley of Lemuel? The place Bountiful? Yes, of course, if you have enough faith. Maybe not if you want to see a little evidence before you believe. Ah, a strange turn of events, with apologists poking the critics for some evidence. But they do have a case to make, a case we’ll look at in more detail in the near future.

As a more important reminder, no matter how interesting the Arabian Peninsula evidence is, there will always be plenty of room for doubt and reasonable arguments against it. I think that’s a vital part of the game here in mortality. The purpose of the evidence, in my opinion, is to help those who are willing to exercise faith to get over roadblocks and keep moving forward, in faith. Faith is required to accept the Book of Mormon–but it seems that faith of some kind is also required to accept theories that he fabricated all of its details on his own, with or without the help of the best libraries of his vicinity.

You're not the first to make that mistake. 40 years ago I was a missionary serving in Harmony, PA. We were stopped on the street once by someone asking if there was a church visitor's center in town or any other attraction. We had to tell them they were off by most of the state. The old Harmonist Society Cemetery may be the most interesting thing in Harmony today.

Remember, everyone, some of the basics of this whole argument:

(1) To the non-LDS, the theory of gold plates, divine revelation, etc. is so unbelievable on its face that it bears the burden of proof. Not only that, but to meet that burden and persuade the nonbeliever, the evidence will have to be pretty ironclad.

(2) The apologists' theory is that the ancient origins of the Book of Mormon can be demonstrated not just by spiritual means, but also by showing the book to contain elements (chiasmus, Nahom, EModE, whatever) that could not have been known to a 19th-century author or authors.

(3) The "anti" theory says that (a) we see many elements in the book that were hot issues in the 19th century (Indian origins, Protestant theological disputes), and (b) we have not seen anything in the book that was not available to a 19th-century author. Chiasmus doesn't cut it. Nahom doesn't cut it. These things were in circulation in 1820s, ergo they couldhave been seen by Joseph Smith, ergo there's no need to resort to a supernatural explanation.

On some counts, we nonbelievers see the apologists as performing just miserably. One example is their silly confusion between using chiasmus in one's writing (which anyone familiar with the KJV in the 19th century could have done) and being consciously aware of chiasmus as a literary technique. These are very different things, and of course the latter idea (being consciously aware of chiasmus as a literary technique) is completely irrelevant to the argument. The fact that this chiasmus argument continues to be advanced makes me think the apologists are not operating in good faith.

The fact that the nearest early Arabian map which we know about today was 300 miles away from Harmony is likewise irrelevant to the "anti" theory. For the "anti" position to prevail, one need only to know that such maps existed in Joseph's time and were in circulation in his region. The "anti" side does not need to find an extant map in Joseph's backyard. Anyone can see that, after a lapse of nearly 200 years, such a find is unlikely. Anyone can see that, after 200 years, texts that were once widely available will now be found only rarely. Early editions of the New England Primer were once found in thousands of New England households but are now quite rare.

The apologists' job is not to persuade the nonbeliever. The arguments they make indicate to me that they realize this, and that they see their job instead as reassuring the faithful. Their job is not to dispassionately look for the truth of Joseph Smith's claims. Their job is to allow the faithful to continue to believe even in the face of evidence to the contrary. This is why Jeff finds these arguments so much more compelling than I do.

Again, Orbiting Kolob posits the "anti Gold Plates" — a vast library of books, maps, charts, Biblical studies, tomes of Hebraic legends, and so forth that Joseph Smith must have had. There is literally no evidence for such a library, but Orbiting Kolob simply assumes it must be there–because the alternative of the real gold plates is in his view impossible. So he clings to another impossibility instead, demonstrating great faith in this mysterious library, and in concepts such as "Chiasmus is easy as pie; everyone who's read the King James Bible will naturally write sophisticated chiasms without effort or issue.!"

Do you really think Chaismus on highly advanced levels, such as Alma 36 and King Benjamin's speech, is just bound to show up, Orbiting? That is quite the demonstration of faith you've got there. You're an atheist, yet you cling, faithfully and stubbornly, to positions that have a great deal of issues themselves. Your claim that chiasmus is easy and can be done without trying is one: where is your evidence? Sure, some small, minor chiasmus will happen over a short textual space: but advanced, detailed, multi-level chiasmus as demonstrated frequently by the Book Of Mormon? Nonsense: you assume facts not in evidence.

You assume that Joseph had all these tomes and books available, yet provide not one scintilla to refute everyone who stated that Joseph didn't have any other books: you have faith with zero evidence that they are all wrong. It's a religious belief you hold; it simply must be true, with no evidence at all to support it, and when the available evidence demonstrates the complete opposite. Just as you hand wave away the 320 mile difference with "Well, there must have been others! It's irrelevant anyway because it simply had to have been there!" You demonstrate more blind faith on no evidence at all than any Mormon.

Orbiting Kolob said "The apologists' job is not to persuade the nonbeliever. The arguments they make indicate to me that they realize this, and that they see their job instead as reassuring the faithful. Their job is not to dispassionately look for the truth of Joseph Smith's claims. Their job is to allow the faithful to continue to believe even in the face of evidence to the contrary. This is why Jeff finds these arguments so much more compelling than I do."

I agree pretty much with that assessment. If there was ironclad proof, we would not be having these conversations. And I do not know of any LDS scholar that is touting any of the evidences that have been discussed here as proof of the divinity of the Book of Mormon. That proof will have to come through divine means.

The evidences, such as Nahom, Nehem, etc. are just that, evidences. Taken by it self, it has some significance because it is in the right place and the right time, and there is an ancient burial ground in the region.

However, the additional evidences that have been found, in the right places in relationship geographically to Nahom, with the right characteristics, give some added weight to those evidences.

Those evidences, even if accepted, do not prove that the Book of Mormon is of divine origin. What all of those evidences do is remove the possibility that the Book of Mormon is a book of fiction springing entirely from the mind of Joseph Smith.

As one poster in another thread has noted, the "apologists" have produced a lot of evidences. Most critics have not dealt seriously with the evidences that have been produced. They just dismiss them, pretty much out of hand.

The attitude towards chiasms found in the Book of Mormon is an example. Orbiting Kolob seems to find them silly (the arguments that they are evidence), asserting, that one need have to be aware of, knowledgeable of chiasmus as a literary technique to produce them. That is an exercise in reductionism, necessary for the mental well being of the critic, of course, but non-the-less fallacious. That a writer may produce simple chiasms unconsciously is not disputed. However, complex chiasms are another matter entirely. And complex chiasms have been found in the Book of Mormon.

Actually, the critics' response to the Book of Mormon evidences is really reductionism to the nth degree. They take every point singly and then reduce that point down to nothing. As Orbiting Kolob said, the fact that there were maps floating around anywhere within three hundred miles that had the name Nehem on them, is good enough for him. It doesn't matter what the odds are, the fact that there was something, anything with any possibility, however remote, is good enough.

Orbiting Kolob feels that the apologists are failing miserably. Not hardly. Well, maybe failing to convince the critics. But a critic who demands ironclad proof and does not deal with the evidence that is presented is hardly being a critic. Just obstinate. However the apologists are producing evidence bit by bit that the Book of Mormon is not a fairy tale.

If one were to go back and look at the various models that had been developed by LDS scholars over the years, based upon Nephi's sparse description of the route the group took from Jerusalem to Bountiful, they pretty much fell in line with the discoveries that have been made throughout the subsequent years.

The skeptical response has been pretty anemic. Jeff has posts about a couple that have actually tried to make some critical, reasoned points. But to most, not believeing is enough.

I really wish there was some way of quantifying the odds for and against some of the points that have been raised. It might help the discussions a bit.

Glenn

No vast library would have been needed. The amount of material Joseph would have had to see and hear is not at all extraordinary. We all encounter far more information over the course of time than we're aware of. Joseph would merely have had to listen to a bunch of sermons, pay attention to the discussions going on all around him, and, yes, see a map or two. Nothing far-fetched at all.

And the vast chiasmus of Alma 36 doesn't really exist. It's an apologetic fiction constructed by leaving out a fair amount of non-chiastic material.

Also, I'm not exhibiting any kind of atheistic blind faith. I'm merely adhering to a basic, widely shared naturalistic methodology — the exact same one used by Mormons for every other topic.

I think that's a fair take. Yes.

Non-Mormons find it plausible by default that someone trying to imitate Biblical style will do a lot of chiasmus. No preserved diary entries by Joseph Smith saying, "I love this chiasmus stuff!" seem necessary. Non-Mormons find it plausible by default that Joseph Smith or some collaborator might at some time have seen a map of Arabia, even though the only currently confirmed copy was 320 miles away from where he was when he dictated the Book of Mormon.

In a sense, yes, this is faith. But you know, everyone has to exercise some of this faith. Mormons, for instance, assume that the prophet Mohammed produced the Qu'ran by some means other than divine revelation. Where is the evidence that Mohammed was such a gifted Arabic poet? Non-Muslims don't need to prove that Mohammed was a poet, though. Great poets are rare, but much less rare than prophets.

The chances that any random person would learn to speak in chiasms or acquire tidbits of Arabian geography are low. But the chances that a con artist working an ancient scripture scam would do both those things are high. And the con artist wouldn't leave much evidence, either. Con artists are, thankfully, not that common. But unfortunately they are much more common than prophets. So that's how this looks to a non-Mormon.

Orbiting Kolob feels that the apologists are failing miserably. Not hardly. Well, maybe failing to convince the critics. But a critic who demands ironclad proof and does not deal with the evidence that is presented is hardly being a critic. Just obstinate.

Actually, the apologists have failed miserably to get any of their arguments into peer-reviewed, non-LDS journals, and they've failed miserably to persuade the world at large of the Book of Mormon's historicity.

The world at large does not exactly demand "ironclad proof," though it rightly demands something close — something commensurate to the audacity of the claim. Mormons would demand the same if confronted with an assertion that, say, Warren Jeffs was the true prophet. If Jeffs were to defend this claim by citing a golden tablet with a Hebrew inscription saying "Warren Jeffs is the true prophet," we would want to see that tablet. How many LDS Mormons would be satisfied if Jeffs then said, "Well actually I no longer have it, because the angel who showed it to me absconded with it. But hey, here's a statement from a bunch of my followers saying that they saw it, for reals, trust me"?

As I said, I (and the world at large) are demanding no more from LDS apologists than they would demand from anyone besides themselves.

Again, both OK and James fail to address the matter at hand, even the post of Jeff: Just having the name "Nehem" on a map simply does not explain how Joseph Smith got everything else right. No one has offered that explanation. River Laman, the plausible Bountiful, Nahom being a place of burial… none of that was on the map, but it's there in reality.

Of course, minimizing the difficulty of the Book of Mormon makes it easy to issue this challenge: Orbiting, you are much more educated that Joseph was. Surely you've been exposed to far more information than he was.

Please duplicate the Book of Mormon. Should be easy if a simple fraudster like Joseph could do it. In fact, just do a work the size of, say, the book of Jacob. Piece of cake.

James, the same thing goes for you. The problem with the "Joseph was a fraud!" is that Joseph would have had to become an expert in so many things that, well, it seems impossible. Take the Book of Jacob and the Olive tree stuff: how on earth did he get ancient olive cultivation correct? Someone who knew how to grow olives wrote that chapter. And knew how the ancients grew them. It wasn't standard US agricultural practices, that's for sure. Next, King Benjamin's address is a perfect match for a speech given at the Hebrew Feast of the Tabernacles. Whomever wrote that text checked off lots and lots of boxes there–again, who knew that? More to the point, nobody noticed until the last 20-30 years ago. What you are assuming is that Joseph Smith was such a genius that he recognized and wrote tons of things that no one else for over 100 years noticed. It's not like there haven't been really smart readers of the Book of Mormon; just that we have more educated ones.

Are you really suggesting that Joseph Smith somehow acquired a level of education that wouldn't be duplicated until the late 20th century, and that he left all these clues in there for a potential audience a century later? You do realize how unlikely that sounds, right? But you have to argue that, else you have to accept his story. You have to assume that he knew that what seemed silly and clearly wrong at the time would in fact prove him right, like Bethlehem being part of the Land of Jerusalem; or Alma being a male Jewish name, or cement being found–all of which were attacks leveled at the Book of Mormon but have been proven to be bulls eyes.

You have to assume that Joseph was a master theologian (the book of mormon Christianizes the Law of moses, not exactly something done before), intimately knowledgable in Jewish law and custom to an almost imaginable degree (after all, all the Hebraic law and poetry and other stuff is only being discovered over a 100 years after the fact); a master at war and law and doctrine and stories and details.

Where is the evidence that he was any of that in 1829? There is none.

Really, Anon, you've been gulled into seeing a lot of stuff that escapes us gentiles. The Book of Mormon is just not all that wonderful. Its language is frequently bloated, its characters thin, its actions repetitious, its conflicts often childish (e.g., Coriantumr vs. Shiz is worthy of a comic book), its plots amateurish; what is best in it is stolen from the Bible. Its author was clearly enthusiastic and imaginative, but only within severe limitations (e.g., a complete inability to imagine women characters — not a single woman in the BoM even remotely comparable to Eve, Sarah, Rebekah, Tamar, Bathsheba, Ruth….). It is clearly the product of a single limited imagination, bound to a single time and situation, rather than the broad sweep of an actual history.

In this and many other ways it is so unlike the Bible, which, while also mythic, is obviously rooted in a real history and often brilliant and profound literature. How anyone can read (say) the David story or the Book of Job and then not be terribly disappointed by turning to the Book of Mormon is beyond me.

Sometimes I think the apologists do a profound disservice by leading believers to see the Book of Mormon as great writing — what a sure-fire way to destroy literary taste and judgment.

Someone who knew how to grow olives wrote that chapter.

Nah, someone who read the Bible wrote that chapter. Olive husbandry is all over the Bible.

See, you Mormons do lie, deceive, twist information, and hide facts!! I knew it and this proves it! /sarc

Well, I guess you see what you want to see. "You can bring a horse to the water, but you can't make him drink." Personally I think the Book of Mormon is the literary wonder of the ages, right alongside the Four Gospels in perfection and beauty…and far excelling anything that I've read by Shakespeare, Plato, Homer, Tolstoy, and the like. I find such writings as Alma 36 and King Benjamin's Discourse to be glorious, a perfection of beauty. But trying to explain it to some people is like explaining colors to a blind man. That's how it looks to me. Thank God we have our constitutional liberty to believe what we want to believe. You do your thing and I'll do mine.

I think the Book of Mormon is the literary wonder of the ages, right alongside the Four Gospels in perfection and beauty…and far excelling anything that I've read by Shakespeare, Plato, Homer, Tolstoy, and the like.

Christian, you're missing so much. I sincerely hope that some day you come to know better.

I would caution my fellow LDS enthusiast to remember that in spite of some strengths in the case for Book of Mormon authenticity, there remain many unanswered questions and weaknesses awaiting further work. Let's be careful about the excitement level and recognize that for those outside the faith, the evidence should never be strong enough to compel belief. There will be good reasons to ignore the evidence for those who aren't interested in seeing it. It is true, but requires faith and humility to accept and to teach. All of us need to strengthen our approach, especially yours truly.

Jeff, I appreciate the civility — especially the part about how seeing the evidence requires a faith some of us don't share — and will try always to respond in kind.

Christian,

As a huge fan of great literature of Western Civilization, I want to say a thing or two. First of all, I, for one, agree that some of the language of the Book of Mormon is intensely beautiful. I reserve this statement ONLY for the doctrinal passages. The history chapters are absolute snoozers: childish, weak, etc. etc.

But yes…there are some beautiful things in there. But, in my opinion (I usually don't add that qualifier because it should be a given that what I am saying is an opinion, and because I know that the appreciation of great art is a very subjective thing) I think the Book of Mormon is the literary equivalent of a small lake. It is deep enough to completely submerge a man, but not deep enough that the man can't swim to the bottom without any special equipment.

Shakespeare, Homer, Plate, Dante, Tolstoy, etc….these guys are oceans. Veritable oceans! There is more richness and complexity and subtlety in the Queen Mab scene from Romeo and Juliet than is found in the entire Book of Alma.

Perhaps the directness of Alma is part of its strength. It is clear, concise, relatively easy to read and understand. But there are few depths to probe there. But in the Queen Mab scene, we get so much. So much. We get a really intense glimpse into a troubled soul, especially as the scene was interpreted in the 1968 cinematic version. We get a cross-section of Medieval Italian society akin to what Canterbury Tales did for Medieval English society. We get unbelievable poetry. There is comedy there. There is tragedy there. At the same time.

And that is just one scene! In a play filled with such scenes.

And don't even get me started on some people you left off your list. Charles Dickens, for instance? Have you ever read A Tale of Two Cities? Granted,…it isn't up to snuff with Shakespeare, but the Christian message is embedded in that novel from the beginning to the end for those who can see it. And for those who can't, you at least have a really good story in your hands.

So…the Book of Mormon is definitely worth the read. The doctrinal explications are certainly of great value. And the language, to me, is quite beautiful. But in terms of the power of truly great art? …Nope. It doesn't hold up.

And in terms of religious complexity and profundity…it can't hold a candle to the Bible. But as a Mormon, I know you will never agree with that statement. You've been very subtly poisoned against the Bible all your life, if you grew up in the church. Mormons are not capable of seeing that book for what it is. "…as far as it is translated correctly…" You know what I mean.

I'm not sure what you mean, Jeff, by "the evidence should never be strong enough to compel belief". Do you mean that God deliberately keeps evidence below threshold, in order to test people's faith? Or do you just mean to remind Mormons that compelling evidence is a very high bar to clear?

I'd certainly agree with the second option. It's just going to be very, very difficult to identify anything in the Book of Mormon, or its production, which is really impossible to attribute to fraud. Intelligent con artists are surprisingly resourceful; going to unusual lengths, in order to perform seemingly impossible feats, is precisely what these people do. In regard to apparent knowledge of ancient Arabian geography, for example, it's always going to seem more plausible to a non-Mormon that Smith somehow got information from a source, even if we cannot now confirm this, than that he received golden plates from an angel. After all, we can't confirm the angel or the plates, now, either.

So I would say there's simply no chance at all that NHM or Shazer or Bountiful is ever going to convince non-believers that the Book of Mormon is a true revelation. This doesn't mean that Arabian archaeology in connection with the Book of Mormon is completely pointless, however. I think it's kind of like a weight that is free to slide back and forth on a scale. If something else makes the scale tip, then this weight can slide over and tip the scale a bit more heavily. I think it's reasonable for Mormons to read the recent posts here and feel encouraged in their faith.

Conversely, however, skeptics are also likely to have their doubts further strengthened: a good map was within plausible reach for an energetic con artist with collaborators; so was a translation of Enoch 1; and so on. The weights slide, depending on how the scale is already tipped. In this sense, Nephi's journey through Arabia, or the story of Enoch, may be interesting, but they will never be more than sideshows. The scales get tipped first by things like New World archaeology, or the content of the Book of Mormon and Mormon doctrine, or Joseph Smith's polygamy, or personal experience.

On some of those heavyweight topics the Mormon case seems difficult to plead, to me. On others, perhaps, it is strong. At some point I'd be interested to see what Mormons consider their strongest grounds for belief. What really tips the scale first?

I had several English classes at university….writing, grammar, sentence structure, rules, all the boring stuff, tons of paper writing and research, all four years at university. Never, ever, ever was chiasmus mentioned. Never heard of chiasmus until the Book of Mormon scholars brought it up. Even when learning Shakespear and other famous writers.

So to the critics…….not everyone is aware of chiasmus in this day and age. But Joseph Smith was??!! OK…..he was uneducated…..no, wait, he WAS educated…..no, hhmm, he was a genius in certain things….no proof he read hundreds of books, but he did, he did! He just had to! Nope, the devil made him do it.

@ Christian Adams….I agree with you about the Book of Mormon.

Thanks to dedicated LDS scholars I have learned so much about the BofM. I understand the message better, the stories woven in, the characters, the complexities, the wars, etc.

I never knew of the hidden themes either. Now that I know all this and understand it, a light has come on.

TexMex

Hidden themes exist in all complex stories/novels, etc. And they can exist WITHOUT the author being aware of them. That is what the entire field of literary criticism is all about: finding these themes and bringing them to light. The creative process cannot be easily described in nice tidy language. Authors speak of creating their characters and being surprised as they take on a life of their own and begin to dictate the writing process. Being a painter who also teaches art history, I can guarantee you that artists are never fully in control of their creative acts. Things happen that the artist is never aware of, but other see it, point it out. Even the artist might be shocked. Hidden themes is poor proof that a book is divine.

@anonymous 11:48:

Let's try it this way, then. Just why is it so hard to imitate Biblical style? Why would it be hard to perform chiasmus while doing so? I mean, what exactly is the argument?

I mean, I can make a stab for a few lines, off the top of my head:

Behold, there was a man named Jeff; and he dwelt in an eastern land for a time, as a sojourner. And it came to pass that he kept a record, and the name of his record he callled "Mormanity". Mormanity was the name by which he called his record, forasmuch as it had to do with that which concerned the Mormons, but also with that which would concern other people, yea, even those among whom he dwelt as a sojourner, in the eastern land. Even so it came to pass, in the days of the man named Jeff.

It's really not hard; try it. Sure, that's just a few lines. But just what is it that would stop me from going on like that for as long as I wanted? I kind of think it would get easier as I went on. Actors playing a part get into it, and have no trouble speaking in character for months on end. Novelists who use first-person narration maintain a fictitious voice for hundreds of pages.

So just what is the problem? Why couldn't Joseph Smith have done as I just did, and keep it up?

(I apologize for the historical inaccuracy by which the above quoted text implies that Mormanity was aimed significantly at a Chinese audience. It's easier to work in some chiasmus if you give yourself license to make up the facts of your story.)

Anon 11:48, think about a five-year-old child who says, "I wanna go swimming in the pool!"

This child is using a prepositional phrase, "in the pool."

Has the child ever heard of prepositional phrases? Nope. But obviously that does not prevent the child from actually using a prepositional phrase in a sentence. In order to use prepositional phrases, one does not need to consciously know the technical term used by specialists to denote them. All that is needed is for the child to hear prepositional phrases being spoken around her, and to imitate their use. This is the way we all enlarge our language skills: by imitating and remixing the words, grammatical structures, and rhetorical techniques that we encounter in conversation and, later, in reading.

Ditto for chiasmus. In order for Joseph Smith to use chiasmus, he need only imitate the King James Bible. There was absolutely no need for him to have been aware of the term chiasmus or consciously understand it as a common biblical rhetorical figure — just as there was no need for the child to have been consciously aware of the term prepositional phrase.

He need only have read, imitated, and remixed, which is what we all do all the time.

Consider also the Book of Mormon's use of "And it came to pass." This, too, is a rhetorical figure, and it too has a technical name: anaphora. (Anaphora is the repetition of a given word or phrase at the beginning of successive sentences.)

Do you really think Smith had to be consciously aware of the term anaphora in order to use "And it came to pass" repeatedly? Of course he didn't. He could simply pick it up in the course of imitating the KJV.

Chiasmus is no different.

The fact is, people routinely use a variety of rhetorical figures without ever being aware of their technical names — without even knowing they have technical names.

Do you think a person needs to be aware of the term hyperbole before they can say, "I'm so tired I'm about to die"? When it's minus-20 degrees outside, does someone need to have taken a rhetoric course and learned the term litotes before they can say, "It's a bit brisk this morning"?

Chiasmus is another nothingburger. No patty, no bun, not even any mayonnaise.

There's much more to the chiasmus issue than Orbiting says. I discuss some interesting issues and investigations on my LDSFAQ page about Chiasmus in the Book of Mormon.

Take a look at the video on the discovery of chiasmus done by John's son. A cool story. You can see it and a lot of related info on the Book of Mormon chiasmus page at chiasmusresources.johnwwelchresources.com/.

Also see the book, Chiasmus in Antiquity: Structures, Analyses, Exegesis, first published as Chiasmus In Antiquity: Structures, Analyses, Exegesis (Hildesheim: Gerstenberg, 1981). This is a significant scholarly text with mostly non-LDS contributors and a positive forward from one of the most important 20th century Bible scholars, David Noel Freedman. A hard-to-read, poorly formatted version is available at the Maxwell Institute for free.

Chiasmus is one of the things that add literary value and beauty to the book that our critics continues to deride as lacking serious literary value.

Yes, chiasmus can happen by chance. That's been an important point Welch has made for years, but he also offers tools to help differentiate crafted chiasmus from random accidents. That's also an issue where one can apply statistical tools. An example involves a letter Joseph wrote to Emma where someone thought they found chiasmus.

The issue of olive culture is much more than a nothingburger. The Book of Mormon involves details that seem to go beyond what a savvy reader would pick up from the Bible. There's a whole book on this: The Allegory of the Olive Tree: The Olive, the Bible, and Jacob 5. You can read the text online at the Maxwell Institute. But if you don't seriously consider the evidence, yes, it's all negligible, irrelevant, and just a nothingburger. But for those willing to take a bit, there's a lot of flavor and nourishment. But you do have to take the wrapper off and chew a bit. Yeah, that's the bad news. Chewing is required. Can't just sit back and wait for the delicious glucose injection that the airlines give in place of meals these days (OK, slight exaggeration).

Terryl Givens's Oxford University Press publication, By the Hand of Mormon: The American Scripture that Launched a New World Religion, also discusses chiasmus in the Book of Mormon. Not just a Mormon press for a Mormon audience.

re Jeff 12:01, Part One: Yes, there is indeed more to the chiasmus issue than I mentioned above. Yes, there's more than one chiasmus argument out there. There is, for example the argument that Alma 36 is too complex for Joseph Smith to have composed. But that's a separate argument — and LDS apologetics is still atrocious. Let me explain what I mean.

Because I was responding to a preceding commenter, in my comments above I was referring to one very specific (and very common) apologetic argument about chiasmus — an argument that is totally bogus but nonetheless still widely circulated. It's the argument that depends on this deductive reasoning (I'll break it down to make the problem as clear as I can):

Major Premise: In order to write chiasms, a writer must be consciously aware of chiasm as a rhetorical figure.

Minor Premise: There's no way Joseph Smith could have been consciously aware of chiasm as a rhetorical figure.

Conclusion: Therefore, Joseph Smith could not have written chiasms.

This syllogism is not sound, because even though the minor premise is true, the major premise is false.

Note how those who make this argument allocate their intellectual energy, spending almost all of it on demonstrating the minor premise while all but ignoring the major premise. Again, let me make this as clear as possible:

Major Premise: In order to write chiasms, a writer must be consciously aware of chiasm as a rhetorical figure. [Crickets chirping.]

Minor Premise: There's no way Joseph Smith could have been consciously aware of chiasm as a rhetorical figure. Here, instead of chirping crickets, we find tons of research here about who published what about chiasmus, and when it was published, and where it was published, and so on. Tons of wasted energy, actually, since I know of exactly no one who has ever thought that Joseph Smith was consciously aware of chiasmus as a literary device. Why spend so much energy amassing evidence against a non-existent strawman? To snowball the believer and produce the illusion of genuine scholarship. All of the research with none of the logic.

It's shameful, Jeff. Those of us who are used to evaluating arguments shake our heads at this stuff and say, "These guys are just jokers."

To be continued.

The problem here — the problem with the argument that Joseph Smith could not have written chiasms on his own — is not limited to the fact that the reasoning is unsound.

It's not just that the argument is bogus but that it is still being circulated widely, even by the Church itself*, and that not a single Church official or authoritative apologist has had either the intellectual or the moral integrity to take it out of circulation — to step up and say, whenever it pops up, "Hey, people, that one is just wrong, and to the outside academic world it makes us look stupid. Knock it off already."

One of the things that needs to happen if LDS apologetics wants to be taken seriously outside the Mormon bubble is for this particular argument to be taken off the table before we are told to move on to the other issues involving chiasmus. Otherwise what happens is that the folks on my side wind up fighting a hydra. What's the point of moving on to fight the next battle before the previous one has been decided?

When a football team makes a touchdown, it has to kick the ball off and give the other team a new chance to score — but not until the previous score has been put on the scoreboard and acknowledged by everyone.

Jeff wants me to kick the ball off to him before acknowledging that I've scored.

He has said, Well, there are other arguments involving chiasmus. But he's not playing fair, because he hasn't prefaced that by saying, OK, fine, you're right about that particular argument. We'll go ahead and put your debunking up on the scoreboard, and my team won't make that particular argument any more….

Jeff wants me to kick off the ball before my score has gone up on the board. That's fundamentally unfair. But then, LDS apologetics generally is unfair. It's rigged, and this is one of the ways it's rigged. This is also one of the major reasons the non-LDS world refuses to take it seriously. It's not that we secular academics are under the influence of Satan or that we refuse to pray hard enough or whatever, it's because people like Jeff — and Dan Peterson and the rest of the crowd that has been recently nudged away by BYU — simply will not play the game by the rules.

* A typical example is provided by this essay from lds.org:

Chiasmus was first noticed by a few nineteenth century pioneer theologians in Germany and England, but the idea had to wait until the 1930s before it found an ardent exponent, Nils Lund, who was able to lay the principle before the eyes of the world in a convincing way. But even at that, it was not until the decade of the 1960s, after much more had been learned about the philology of early Semitic languages, that chiasmus was properly understood and unequivocally acknowledged. Today, articles on the subject are quite common….

As I keep saying, and as is obvious to anyone with the slightest understanding of how people actually acquire and use language, the fact that few people were consciously aware of the "principle" of chiasmus is irrelevant. Yet here is the Church's own website itself telling us otherwise.

To be continued.

I'm probably just beating my head against a brick wall at this point, but in for a penny, in for a pound…. One final note on one final example of the kind of rhetorical slipperiness that cripples the reception of LDS apologetics among genuine scholars.

Writes Jeff, Terryl Givens's Oxford University Press publication, By the Hand of Mormon: The American Scripture that Launched a New World Religion, also discusses chiasmus in the Book of Mormon. Not just a Mormon press for a Mormon audience.

This is not an argument; it's more of an apologetic reflex. The statement makes it appear that the chiasmus argument itself has made it through peer review and been taken seriously by a prestigious university press. That's the appearance, but it's not the reality. The idea is to use Oxford's intellectual authority to lend support to the chiasmus argument, to suggest to the casual reader that this most prestigious of all scholarly journals has found merit in the argument.

The weasel word that does the rhetorical work here is discusses.

Yes, Givens discusses BoM chiasmus. And he discusses it in a scholarly way. He discusses the chiasmus argument as an argument that BoM enthusiasts make and that critics contest, and he engages in this discussion in a way that makes sense for a non-LDS audience, and with a degree of rigor that merits publication by a prestigious university press.

What Givens has not done is himself make the chiasmus argument in a way that could persuade a secular audience and merit publication in a prestigious university press.

There's a difference between discussing an argument and actually making that argument. Jeff and I are both discussing the argument-from-chiasmus, but only one of us is making it.

The fact that someone has discussed the chiasmus argument in an intellectually legitimate manner does not mean that he has made that argument in an intellectually legitimate way.

Jeff's statement misleads readers by confusing the discussion of the argument with the argument itself. I'm not saying Jeff is doing this consciously and deliberately; more likely, he's just performing what by now has become a standard apologetic gesture. Critic says X, apologist says Y. Critic says "peer review," apologist says "Givens! Bushman!"

Insert Tab A into Slot B. But this kind of theater is not scholarship.

Now excuse me while I go bandage my head.

Just to be clear, nobody is saying that Joseph Smith would have written a lot of chiasms by chance. The simple suggestion is that he was imitating Biblical style, in all the ways he could, and so this naturally included some chiasmus. He didn't have to be aware that chiasmus was a thing, to just notice that it sounded extra-Biblish when he repeated stuff backwards — and to notice that it gave him a way of padding his text out to double length, without being quite so obvious about the repetition.

If you're not into making up texts in archaic styles, then you might well have to take a lot of college courses in literature before you ever heard of chiasmus. But if you ever tried to make up your own scripture, in King James Bible style, you'd get the hang of chiasmus pretty quickly.

Chiasmus, after all, is a Hebraism. That means its's a common literary device in primitive literature — literature that probably started out as oral tradition. That means that chiasmus comes naturally to human beings. It's an easy pattern to do. It helps you keep your story organized, and it sounds nice. It's not rocket science.

James, it took centuries for scholars to recognize the presence and now the important role of chiasmus in the Bible. Translation and formatting of the KJV makes it harder to recognize, whether subconsciously or consciously, though brief bursts of parallelism are easy to see. Imitating chiasm in extensive detail from a text where it is unseen and complex is quite a challenge. But even Joseph as a Biblical genius doesn't account for crafting chiasmus that requires knowledge of Hebrew for its most important pivot point, as we seem to have in Helaman 6:7-13, which I discuss at http://www.jefflindsay.com/chiasmus.shtml. Was this deliberate or just luck?

Orbiting, did you miss Welch's ground-breaking book on chiasmus, complete with a chapter on the Book of Mormon? John W. Welch, editor, Chiasmus in Antiquity: Structures, Analyses, Exegesis (Hildesheim, Germany: Gerstenberg Verlag, 1981). A non-LDS press, a very scholarly work with non-LDS peers and a forward from David Noel Freedman. I was hopiing you'd notice and at least say "maybe a good start." This book is cited by Roland Meynet in Rhetorical Analysis: An Introduction to Biblical Rhetoric. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series 256 (Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic Press, 1998), 392 pp. I don't have access to it at the moment, but according to Noel Reynolds, "Meynet credits BYU’s own John W. Welch, whose 1981 book re-ignited chiasmus studies and helpfully provided the world of biblical scholars with the first complete bibliography of chiasmus publications, enabling contemporary scholars to get a grasp on the extent and quality of the work that had already been done."

Related to the issue of chiasmus in the Book of Mormon is the Hebrew tool called inclusio, in which a phrase at the beginning of a passage is mirrored at the end to mark a section. Interesting insight into a sophisticated case (or 3 related cases) of inclusio in the Book of Mormon is treated by Reynolds in a peer-reviewed publication, which I suppose will never satisfied because the satisfaction your looking for is gouging the Church at all costs–my take on what you've previously said about your agenda here. But here's the reference, if you care to take a look: Noel B. Reynolds (2015). The Gospel according to Mormon. Scottish Journal of Theology, 68, pp 218-234. doi:10.1017/S003693061500006X, available for download at http://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub/1479/.

Even if you don't like the internal complexity of Alma 36, you have to at least notice that the opening verse and the closing verse restate important themes and nicely mark the discourse in a Hebraic way. At least give it credit for having a touch of inclusio, but I hope readers will look at my chiasmus page and consider the deliberate craftsmanship in Alma 36, whose clear pivot point so nicely emphasizes the central theme of the Book of Mormon, as does its nicely mirrored outer ends. This is craftsmanship, not an accident based on subliminal recognition of parallelism in nice couplets from, say, Proverbs.

Anyway, Orbiting, you eat up a huge share of the comments with your demands for peer review. Yep, heard you. You've made that point umpteen times. These things take time, so be patient.

Jeff, it really seems we're talking past each other quite a lot here. When I read your responses, I increasingly find myself saying, "Okay, but so what?" Here's an example of a statement of yours that strikes me as one of these irrelevancies:

This is craftsmanship, not an accident based on subliminal recognition of parallelism in nice couplets from, say, Proverbs.

This statement is irrelevant, and worse it betrays a fundamental lack of understanding of how people acquire and use their languge abilities.

I mean, accident? ACCIDENT?

First, if a writer is unconsciously using and remixing literary forms they've encountered elsewhere, that use is not "accidental." None of what I've been saying has anything whatsoever to do with accident. It has to do with the most utterly commonplace human use of language. When a child is acquiring language, and she switches from saying "Me want a cookie" to "I want a cookie," she does so because she has heard others use the standard structure, and she does so unconsciously — and it is not an accident. No one would use the term "accident to decribe this scenario. Your use of the word "accident" in this context is not merely wrong, it's bizarre.

Second, people's ordinary, commonplace language abilities are not just imitative but creative. When the child hears "I want a cookie," the child is able to imitate not merely the words themselves, but the underlying structure. By imitating both words and grammatical structures, the child is able is able to produce entirely new and original statements — not just I want a cookie but They want a car and We need some water, even if the child has never heard these last two utterances before. The appearance of completely new and original utterances is perfectly natural and ordinary.

Once the child has heard He and I are hungry, and She is in the house, the child understands (unconsciously, of course, but that doesn't matter a whit) that subjects can be compounded and that prepositional phrases can be used like nouns as the object of a noun, and now the child can — and will! — mix and match and say You and I are at the mall, and so on, even if she has never encountered that specific sentence before. What matters is that she has encountered the individual word and the relevant grammatical rules.

In the same way, once Joseph has encountered certain Hebraisms in the KJV, even if he is not consciously aware of his knowledge of them, it would be the most natural thing in the world for him to start imitating them and remixing them creatively to create entirely new sentences and even structures of his own. Having encountered sentences that are ordinary but long, and sentences that are chiasmatic but short, it's not a bigcsurprise that he would create a sentence that is chiasmatic and long. Alma 36, even if it is a 39-part chiasmus, might be impressive, but it's not evidence of ancient origins. It's easy to see it as the result of ordinary human linguistic creative ability.

I go on at such length about this stuff because you seem to think that the authenticity of the BoM is demonstrated by the appearance within it of any structure lacking an obvious counterpart in the KJV or 19th-century English. You seem to think that a writer's use of a certain structure depends on their conscious awareness of that structure as a discrete, named, academically studied object. But if you keep in mind the natural linguistic creativity of the human mind, you see how crazy these assumption are.

You have spent hours on this blog telling us what a pathetic writer Joseph Smith was. In spite of all the great literature he had been exposed to in the Bible and in other works of his day, you tell us that he completely failed to pick up the basics of writing a plot, of developing a character, of having lots of stories about women, of having the complexity, tension, and exploration of the human condition that is all over the Bible and other good literature that he was just too dull to pick up. He shows an almost absurd lack of skill in your incessantly shared viewpoint.

Yet, when we report that a relatively recently discovered and important but easy to miss Hebraic poetical structure is found extensively in the Book of Mormon showing craftsmanship and sophistication on par with its use in the Bible, you roll your eyes and say of course, this would be the easiest thing in the world for someone to naturally, subconsciously absorb from the Bible.

Detailed poetical chiasmus in the KJV Bible is hard to notice even AFTER students read about it and know what to look for. It is obscured by translation and formatting. So how does that get absorbed? It boggles the mind that Alma 36 or Helaman 6 would just be spewed during random dictation without deliberate craftsmanship when the critical themes of Alma 36 are so powerfully presented and amplified using chiasmus as a tool, or when Helaman 6's 10-step tight, concise chiasmus requires a knowledge of Hebrew at the key pivot point. I suppose young Joseph absorbed that as well?

Have you taught writing to young people? Do your students naturally craft sonnets without knowing anything about rhyme schemes after having heard a few poems read to them? Or if you reformat a sonnet so it looks like prose and bury it among other prose, will they pick up on the scheme of sonnets on their own, without even knowing that it is poetry, and then unconsciously write detailed, complete sonnets when asked to write something literary? Of course?

I don't think this line of reasoning will withstand peer review.

Also, I read the Scottish Journal of Theology article, and once again I find myself scratching my head and saying, "So what?"

For those who can't access the article (or don't want to waste their time), here's the thesis (the bolding is mine):

It may seem strange that even though The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is now widely recognized for its membership growth and its increasing social significance, the canonical LDS scriptures receive little scholarly attention outside of Mormondom. While a continually growing literature tries to find new and convincing explanations for the content and production of the Book of Mormon, only a few studies focus on the doctrinal messages of the book itself—on what it teaches. Over 150 million copies of the Book of Mormon have now been published in 82 languages by the Utah-based church, and the book itself is now published by an increasing number of secular presses.

The following article finds that there is a consistent "doctrine of Christ" or "gospel of Jesus Christ" taught throughout the text that displays both similarities to and differences from the way to salvation laid out in the Bible. Three definitional passages are identified and analyzed. The full content of this gospel formula can be established through a cumulative analysis of the partial statements included in each of these three passages. It is further claimed that the results of this analysis open the way to a much richer and more systematic interpretation of the numerous sermons and prophecies reported throughout the Book of Mormon. In this way, the text is found to reward readers who are willing to assume that it may be a redacted whole in the same sense that Robert Alter has explained his interpretive approach to Genesis and other materials.

So, what is it that Reynolds has managed to get published in a peer-review journal?

Has he gotten his academic peers to acknowledge the cogency of an argment that there are elements of the BoM that defy naturalistic explanation?

If so, that would be big news, and it would justify Jeff's reference to this article in his apologetics. But of course Reynolds has done nothing of the kind. What Reynolds has gotten published in a peer-reviewed academic journal is an argument that the BoM teaches a distinctive theology; that this theology is expressed using certain literary modes and devices, such as inclusio (which is present in the KJV); that the theology is richer than previously thought; and that the BoM rewards those readers willing to assume the book is ancient.

The article does not argue that this assumption of ancientness is justified. The article is not apologetic. In fact, the article's opening paragraph sets it apart from such apologetics. It specifically distinguishes itself from the many (non-peer-reviewed) efforts to "to find new and convincing explanations for the content and production of the Book of Mormon." So why would Jeff even cite this article?

If chiasmus really is a subtle and hard-to-see thing in Biblical Hebrew, unsuspected through the ages until recent times, then I might grant some weight to the argument from chiasmus in the Book of Mormon.

But is all that about chiasmus really true? Or is the recency of chiasmus as a recognized concept really only a matter of it being a recent argument in Mormon apologetics? I'm afraid I'm too cynical and jaded to accept that chiasmus is all that, just because someone says so. As the Good Book says, "Citation needed."

I'm particularly suspicious of the claim that Book of Mormon chiasmus had to be miraculous, because my own rather weakly supported impression is that the early 19th century was a great time of rhetoric and oratory. People listened to hour-long sermons. For fun. And, especially when you've got an experienced and discerning audience, there's a lot of art to preaching.

If people are going to listen to you for an hour, your message has got to be pretty heavily structured, or people will just lose the thread. "Tell them what you're going to say, tell it to them, then tell them what you told them." Apprentice preachers learn that formula even today, in the age of twenty-minute sermons. So I've never sat through any hour-long 19th century sermons, but just as a hunch, I'm pretty sure they must have had a lot of repetition in them. Simply repeating and repeating would have gotten monotonous; preachers who wanted to pack the pews would likely have upped their game beyond that. So I'd be surprised if chiasmus wasn't a fairly common rhetorical device in Joseph Smith's own experience.

He might never have heard of the term by name. But then again, he even might have. Rhetorical devices have been studied, under their formal Greek names, for millennia. I myself remember learning about synechdoche, anaphora, onomatoppoeia, and probably a few others that have slipped from my brain cells now, no doubt for want of structured repetition.

So, I'm prepared to learn that chiasmus really is this long-buried secret, uncovered in these latter days to confound the unbelievers. But I'm not prepared to accept that just on a say-so.

Because the use of inclusio as a literary tool is interesting and adds to the literary sophistication of the Book of Mormon. It's a valuable contribution.

As a matter of fact, Jeff, I have taught college-level creative writing, and I can tell you that the most difficult thing for students to learn is how to create characters that readers care about and plots that draw the reader into the story. I've read many a story and poem packed with literary techniques and boring as can be.

The various techniques I've been discussing can be quite powerful when they work in concert with all the other elements that make for great literature. But by themselves they are never enough. There are innumerable poems written in, for example, perfect iambic pentameter — the same meter used so much by Shakespeare — but they're not worth reading at all.

I should add that none of this is to say that students don't learn a lot from applying themselves to creative writing. Among other things, it can deepen their understanding and appreciation of the really great stuff. They might never become great writers themselves, but they'll have a far better understanding of what "great writing" means in the first place.

Anyway, the conflict you're conjuring up here — between (a) Joseph's absorption and creative remixing of literary techniques from the Bible, and (b) his failure to write compelling characters and plots — is not a conflict at all, but an extremely common feature of amateurish writing.

James said, "I'm not sure what you mean, Jeff, by "the evidence should never be strong enough to compel belief". Do you mean that God deliberately keeps evidence below threshold, in order to test people's faith?"

Yes, that's roughly what I mean. God wants us to exercise faith, and only then will faith be confirmed and become more like knowledge. Evidences for the Gospel–the reality of Jesus Christ, etc.–are there and do help, but I suspect that they are insufficient on their own by design. Partly, at least, because God wants us to grow through placing trust in Him, not just accepting the obvious and irrefutable.

He could have Christ return and do massive miracles on prime time TV with global peer review to overwhelm the most committed skeptic and leave them no choice but to believe. Ditto for the evidence for the Book of Mormon and the Restoration. He could prove it all beyond any room for doubt first thing tomorrow morning. But taking away our free agency is not on His agenda.

I suppose I also believe we need faith; but I've never liked thinking of it as something God just demands, on a whim. I don't really think that God could replace faith with proof, even if God wanted.

People sometimes say that we human beings are to God as the characters in a novel are to the author. In a way that's no doubt true, but in another way it's inadequate; because in fact we are not even really to God as a semicolon on page 3 is to the author of the book. We are to God, as a semicolon is to God. We are just patterns God has made. We are rather more complicated as patterns than a semicolon, but we are in the same category — we are the same kind of thing.

Suppose a bearded Jewish guy did appear today, calling himself Jesus and performing great wonders. The wonders might prove that he was superhuman, but they could not prove him divine. The Star Trek being 'Q', for example, was a hypothetical entity who could perform any wonder that humans could experience; and yet compared to the God of the Abrahamic religions, the author and editor of reality itself, Q would be just another created thing — a fancier semicolon. Q would not deserve worship.

Based on those reflections, I figure that it is literally impossible for God to prove to us that God — as opposed to a merely Q-like entity — exists. And so faith really is necessary. God could maybe prove more to us than God does prove; but why? The essential things would always remain unproven. God would have to stop proving things at some point. Who's to say that God, in making things as they are, failed to choose the right point?

@anonymous 7:50 Nov 6:

The question was, How plausible is it really, for Joseph Smith to have amassed all the expertise needed to fake the Book of Mormon?

I admit I can't really answer. It's a big question, not because the Book of Mormon is so extraordinary, but just because it is a fairly lengthy book. The case for the Book of Mormon is just as much a 'long list' as the attacks of the critics.

The fraud hypothesis imagines that Smith may have had some help from collaborators, and that years of preparation may have gone into the effort, even though part of the trick was to make it seem as though it was all done in a few months of full-time dictation. The preparation wasn't necessarily all deliberate; this was not Ocean's Eleven. But stuff that Smith and perhaps some friends had collected or thought about for years ended up getting used in the Book of Mormon. And then, if someone much later tries to reconstruct these sources, they are at a basic disadvantage: Smith and friends had no obligation to be systematic. They could pick and choose ideas at random, from anywhere they had ever found them. So there isn't necessarily any trail for a critic to follow. The long list of Book of Mormon evidences may all be individual needles in the haystack of history.

Beyond just offering that blanket excuse, I can offer one systematic criticism. A lot of the Book of Mormon evidences seem to me to be so-called 'Texas sharpshooter fallacies'. (The name is from the story of a Texan whose barn was all painted with targets, each with a bullet hole in the very center. Dang fine shootin' — except that in fact he had simply shot up his barn at random, and then painted bullseyes around every hole.) In this case what I mean is that the actual evidence isn't nearly as compelling as apologists make it out to be. The impressive fits are mostly constructed in hindsight — and this is much easier to do than one might think. A text like the Book of Mormon has a lot of ambiguity. Knowing in hindsight — about Arabian geography, or ancient Middle-Eastern olive-growing, or whatever — one can select particular interpretations of the ambiguous text so as to make the text seem to fit reality very well. And the proof that this set of interpretations is correct is that it makes the text fit the reality! But this is circular. The interpretation is the bullseye painted after the shot.

Just to clarify: the accusation of 'sharpshooter fallacy' can be a tough rap to beat, but it isn't just a hopelessly stacked deck. One just has to show that the way one is interpreting the text, in order to provide such good fit with whatever facts are involved, is not an arbitrary reading with a lot of ambiguous wiggle room, but is really the most natural reading of the text. For example, one should be able to argue that one would naturally read the text the same way, and draw from it the same conclusions, even if the confirmatory evidence were not there or were not known. This is how you establish that the target really was already there, right where it now stands, before the shot was fired.

Arguments for the naturalness of an interpretation are notoriously subjective, and so it may still be hard to get a determined critic to stop calling you a Texas sharpshooter. But some people are prepared to be convinced — not necessarily that you're right, but at least that you aren't guilty of this particular fallacy. And even just recognizing the issue and making a decent stab at dealing with it will get you a lot of credit with open-minded listeners.

Jeff, this might seem pretty tangential, but I'd like to respond to your statement that God could prove [the authenticity of the Book of Mormon] beyond any room for doubt first thing tomorrow morning. But taking away our free agency is not on His agenda.

To me, your use of agency here doesn't make sense. It will take awhile for me to explain — as always, please bear with me.

To me it makes the most sense to think of agency as the capacity to make genuinely independent, self-willed choices, particularly in the moral arena. Thus defined, agency is one of the two key factors (along with language) distinguishing humans from all other animals, whose choices are instinctual (except maybe some borderline apes).

Defined in this way, agency is pretty much species-innate. It's something we have because of our intelligence, our ability to conceive the long-term consequences of our actions, the weakening of our instinctual drives, and many other things — including, if you wish, the legacy left us by Adam and Eve.

Thus defined, agency is not something that can be "taken away" as easily as most Mormons think it can. Questions of agency, free will, and the like come up frequently in my classes, so I've discussed this with a lot of Mormons over the years, and they typically think of agency as something like freedom, as when someone says "Communism was bad because by denying freedom it took away people's agency."

But people in the Soviet Union people absolutely did have agency, properly understood, just as much as Americans. They still possessed the basic human ability to make independent, self-willed choices. Their lack of political freedom certainly changed the consequences of certain choices, but the choices were still theirs to make, and they were still morally accountable for them. They were free to choose to oppose the Soviet regime, in the sense of "free" that matters here, and we know this by the simple fact that many dissenters did freely choose to oppose the regime.

The point is that while political freedom is a good thing, it's not the same thing as agency. Taking away political freedom is not the same as taking away agency.

What does this have to do with your comment I quoted above?

Your comment suggests another way that our agency can (supposedly) be taken away: not by jailing us for making a choice, but by providing us too much information about a choice. You're suggesting that if God makes the evidence for the BoM too obvious, so that the choice to believe in it becomes too easy, that amounts to "taking away our free agency."

That makes no sense to me. Just because we learn stuff that makes our choices easier doesn't mean we're no longer freely and independently choosing.

Suppose that on the eve of a presidential election, we become aware of incontrovertible evidence that one of the major candidates has been spying for ISIS. That evidence would make it a lot easier to choose how we vote, but it would not mean that our choices were no longer choices. Such a situation would not "take away my free agency," it would just make it a lot easier in this particular instance to exercise that agency rightly.

To be continued.

There ARE things that IMHO opinion really can take away people's agency, such as:

— Brain injuries and disabilities that take away the cognitive substrate of free and independent choices. Simple example: Tourette's syndrome.

— Advertising that undermines our conscious, free-willed decision-making. To the extent that such advertising leads us to make "choices" by getting our basest instincts to kick in, then it's taking away our agency.

But can additional information take away our agency? Can additional truthful information ever transform what was a free choice into an unfree choice? It's really hard for me to see how.

It might make sense that, when it comes to belief in the BoM, God wants the choice to be difficult. But that really has nothing to do with the question of agency.

This might seem a subtle distinction –and not worth going into at such length — were it not for the supreme importance of agency in Mormon thought.

I love the book of mormon but not for its literary beauty. It has its moments for sure but it wasn't written by poets or great story tellers. It was written largely by military leaders and refugee colonizers. Why would we expect their style to compare to Shakespeare or Isaiah etc. If a theological history was compiled and edited by your local wards mustachioed Vietnam vet Boy Scout leader what would it look like? Mormon was an awesome guy with incredible faith and Christ-like love despite the things he went through but why should we expect him to be a literary genius or to be able to capture extreme depth in the characters he writes about?

The Book of Mormon is awesome because it contains first hand eye witness accounts of the ministry of Christ, it shows us how to draw near to God, it teaches the pure doctrine of Jesus Christ and it documents the struggles of a people to follow God despite their pride, arrogance and unbelief. It is full of the practical knowledge needed to be a true disciple of Christ, that is why it matters. I understand that some people really like complex poetry and that's cool if that is your thing. It isn't a requirement of discipleship though.

"it teaches the pure doctrine of Jesus Christ…practical knowledge needed to be a true disciple of Christ"

How can the BoM contain pure doctrine when it teaches unchangeable doctrine, one eternal God, no degrees of glory, no temple marriages, no temple ceremonies, no baptism for the dead, no pre-existence of man, no eternal progression or polygamy the way D&C does?

I may be wrong but it seems to me the BoM teaches very little to none of the saving ordinances of the LDS church.

Just to piggyback onto Orbiting Kolob's points above, how do apologists think that chiasmus got into the Bible in the first place? Was there some sort of systematic training program for aspiring Bible writers that told them what chiasmus is and that they need to use it? Or did the writers study earlier scripture and imitate its style? I submit that the latter is more likely, and if they could do it, so could Joseph Smith.

Regarding the Reynolds paper in the Scottish Journal of Theology, the unity and consistency of Christian theology as presented in the Book of Mormon is actually a strike against historical authenticity. Contrast it with the Bible, which presents occasional doctrinal inconsistencies reflecting different views of different authors. And lest someone claim that the consistency is due to redaction by Mormon, let me point out that the Bible has also been redacted, but it's impossible to remove all the inconsistencies.

flying fig, mkprr said "pure doctrine", not "all doctrine".

Jerome said "Or did the writers study earlier scripture and imitate its style? I submit that the latter is more likely, and if they could do it, so could Joseph Smith."

I think that's a valid point. Joseph Smith could have studied forms of poetry in the Bible and attempted to duplicate them if he was thoughtful and intentional enough about it. What I think is significant however, is that these forms of poetry in the BoM, along with other hints to its authenticity, like Nahom, or old world Bountiful, weren't pointed out by Joseph Smith or leaked by his contemporaries. They weren't noticed by anyone until long afterwards.

If Joseph Smith is a fraud, and he was clever and diligent enough to study up on little understood ancient forms of poetry, and to find obscure place names and descriptions of geographic anomalies to add into his book, it would have benefited him to point this stuff out or to have others point it out for him. The fact that he didn't when he would have greatly benefited from it strongly supports a hypothesis that he didn't know it was there.

I don't know what the odds are of these things being random accidents in a fraudulent text, but it doesn't seem like the odds would be very high.

Likewise the general assumption by JS and his contemporaries that the Book of Mormon people covered the entire hemisphere when in fact the text itself consistently and very strictly supports a limited geography supports the hypothesis that Joseph Smith and his contemporaries really didn't know enough about the Book of Mormon to have authored it.

Apparently there's some disagreement about whether and how much chiasmus occurs deliberately in the Old Testament. I can't say who's right or wrong about that, but the existence of the controversy suggests that it isn't glaringly obvious. In contrast, the presence of chiasmus in the New Testament is better established. If so, I have to wonder again how much more likely it would be for Nephites to include chiasmus, given that their only access to it in tradition would be the Old Testament, than it would be for Joseph Smith to use it, given his access to the New Testament.

My point here is that apologists focus on the improbability of Joseph Smith using chiasmus without really considering the improbability of the alternative explanations. They just assume that Nephites would be likely to use it, but that shouldn't be taken for granted. However unlikely it may be that JS would use chiasmus, it doesn't seem all that less probable than the alternatives. Besides, there's chiasmus in the Doctrine and Covenants.

mkprr (and many other otherwise smart people here) completely misunderstand — or refuse to acknowledge — the natural ease with which people acquire and use language, whether at the level of basic grammar and vocabulary or the level of complex rhetorical forms and strategies.

For those of us who argue that Joseph Smith wrote the BoM, there's absolutely no need to show that he was "clever and diligent enough to study up on little understood ancient forms of poetry" like chiasmus. He would naturally have produced chiasmus simply by imitating the KJV. There's no more need for him to have studied up on chiasmus than for him to have studied up on the use of nouns and verbs and prepositional phrases.

Does anyone out there seriously think that JS would have had to formally study ancient rhetoric in order to use the device known as anaphora in order to repeat the phrase And it came to pass? Did my father have to study formal rhetoric in order to look out the window at a downpour and, using the rhetorical technique known as litotes, announce that It's a bit damp outside? Isn't it more likely that he just heard someone else use that technique and then unconsciously started using it himself?

The entire chiasmus argument is laughable. It's stunningly ignorant. It makes those who expound it look like utter fools. Seriously. Run the basic argument past any non-LDS linguist and see for yourself. This kind of apologetics makes otherwise very intelligent people look very foolish.

And FWIW, I find this statement to be very misleading: Likewise the general assumption by JS and his contemporaries that the Book of Mormon people covered the entire hemisphere when in fact the text itself consistently and very strictly supports a limited geography supports the hypothesis that Joseph Smith and his contemporaries really didn't know enough about the Book of Mormon to have authored it.

What's misleading here is the implication that belief in a hemispheric geography was somehow limited to "Joseph Smith and his contemporaries." In fact it was assumed by the Church leadership right up to the end of the 20th century and into the 21st, when the phrase "…the ancestors of the Native Americans" was (quite sensibly) revised to "…among the ancestors of the Native Americans." What we really have here is the inability of the leaders, in spite of their supposed prophetic status, to read their very own scriptures correctly — at least until DNA studies revealed to these prophets a basic genetic truth that God, apparently, could not.

This is not a minor point. Think of how many tens of thousands (hundreds of thousands?) of Native Americans and Pacific Islanders were assured, over the course of nearly two centuries, with complete prophetic authority, that they were literally descendants of the Jews. Oops! Pretty big mistake! Tell me, are there are any plans to discuss this mistake with all of those thousands of recently de-Judaized believers? Any plans to, you know, apologize for the mistake? Does the Church feel no compunction at all for convincing thousands of people of such fundamental falsehoods about their collective history and racial identity?

It seems more than a little disingenuous to dismiss all this as a matter of a mistaken assumption on the part only of "JS and his contemporaries." But I suppose if I'd made such a boneheaded mistake I too would want to downplay it.

Anyway, to those of us outside, it's all just incredibly ludicrous. Whether it's the abandonment of polygamy, the demise of the black priesthood exclusion, or the repudiation of the hemispheric geography, we outsiders find it sadly funny to see a purported "prophet, seer, and revelator," whom we are told cannot "lead the people astray," again and again do just that: leading the people astray, at least until the prophets are corrected by the secular world.