Executive summary: Discoveries from the Arabian Peninsula supporting the existence of a place called Nahom (see 1 Nephi 16:34) face recent criticism for only showing that the NHM tribal name existed in Yemen around 700 BC, not a place with that name. Some argue that Yemeni tribal names don’t correspond with place names and thus, it makes no sense to think that anyone could have encountered “the place which was called Nahom.” Contrary to such claims, there are multiple examples from antiquity of Yemeni tribal names being associated with places. There is also a recognition by some scholars of Yemen that tribal names can be equated with places. The archaeological evidence of the NHM/Nihm tribal name on ancient altars in Yemen makes it entirely plausible that a place called NHM did actually exist in Nephi’s day in a place consistent with the Book of Mormon record.

A New Tactic for Downplaying Nahom

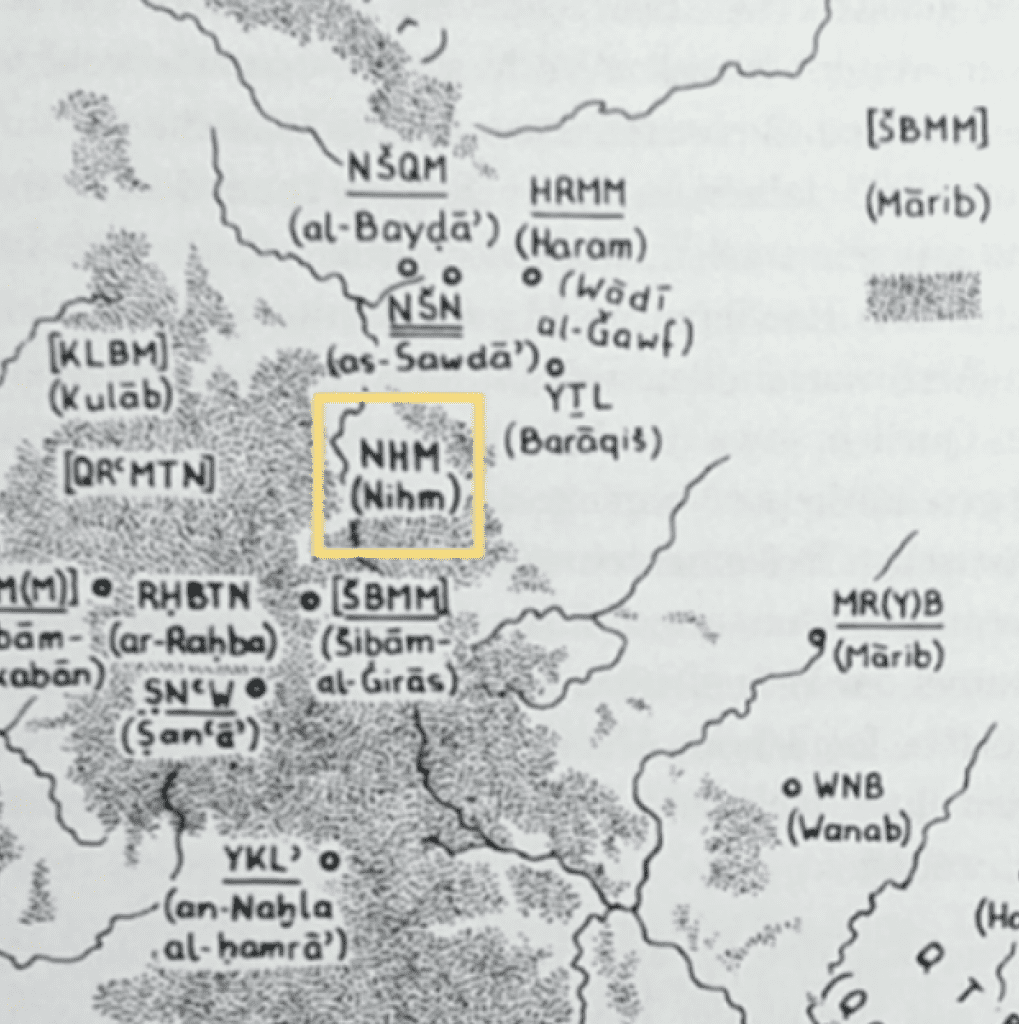

For students of the Book of Mormon, the composite evidence coming from the Arabian Peninsula has greatly strengthened understanding of Lehi’s Trail and also the case for the antiquity and authenticity of the text, at least for the first part of the Book of Mormon, 1 Nephi. While this evidence involves many details such as the candidates for the River Laman, the place Shazer, and the place Bountiful, the epicenter of evidence that plausibly links the other sites of Lehi’s Trail together is the “the place which was called Nahom” (1 Nephi 16:34). Not only is there a place called “Nehem” or “Nehmm” on some old maps of Arabia that correspond to the location of the modern and ancient Nihm tribe (whose name, when I heard it pronounced by a man from Yemen familiar with the tribe, to my ears sounded very close to “Nehem”), but there is recently discovered hard archaeological evidence for the existence of that tribe and their name in roughly the same area extending back to before Nephi’s day based on three inscriptions on altars that were donated by a prominent member of that tribe to a temple at Marib, about 75 miles east of current Nihm lands, dating to the 7th or 8th century B.C. See, for example, Warren P. Aston, “A History of NaHoM,” BYU Studies Quarterly, 51, no. 2 (2012): 79-98 and Warren P. Aston, “Newly Found Altars from Nahom,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 10, no. 2 (2001): 56-61, 71. This is all remarkable news, for it’s not just evidence that a random NHM name existed somewhere in the world, but that there was a place that could be called “Nahom” in just the right location to fit several details of the Book of Mormon. It is a place that can be reached by traveling in the direction given by the Book of Mormon from an amazing candidate for the the River Laman, and can then be the starting point for the nearly eastward journey that Nephi describes after their time at Nahom. The Nehem/Nihm region as a candidate for Nahom is precisely situated to make it possible to not just survive an eastward turn, but to actually reach either one of two strong candidates for the place Bountiful in southern Oman.

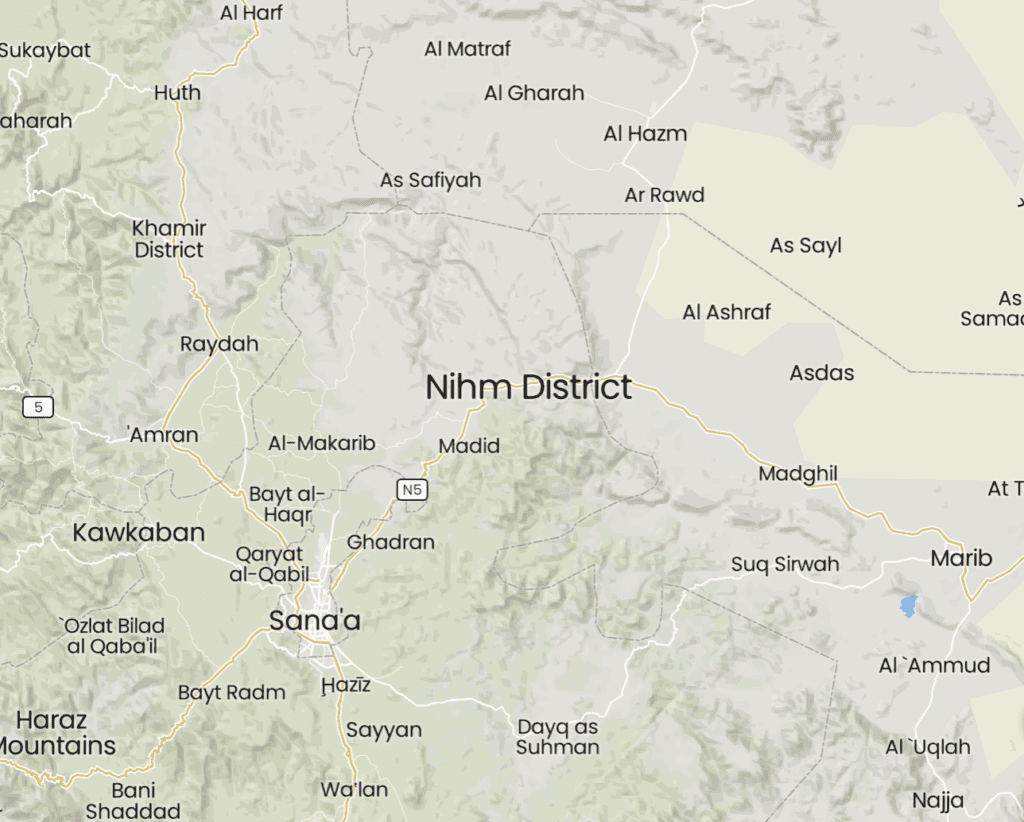

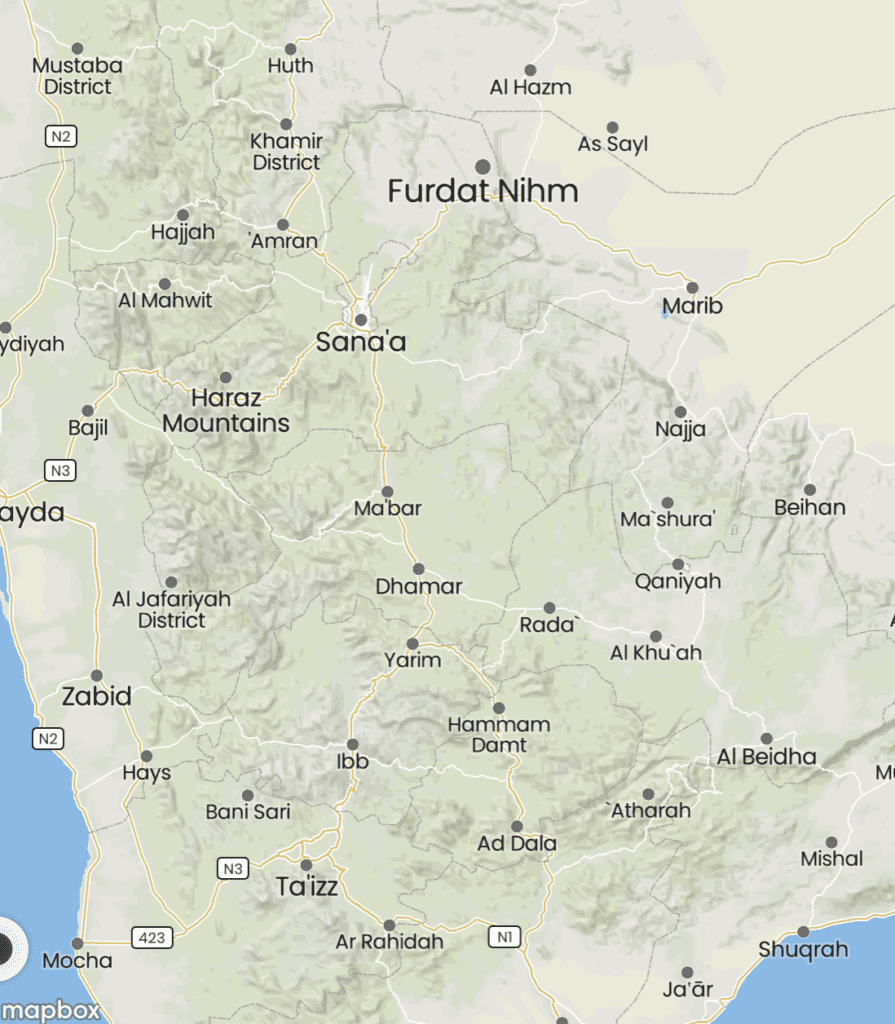

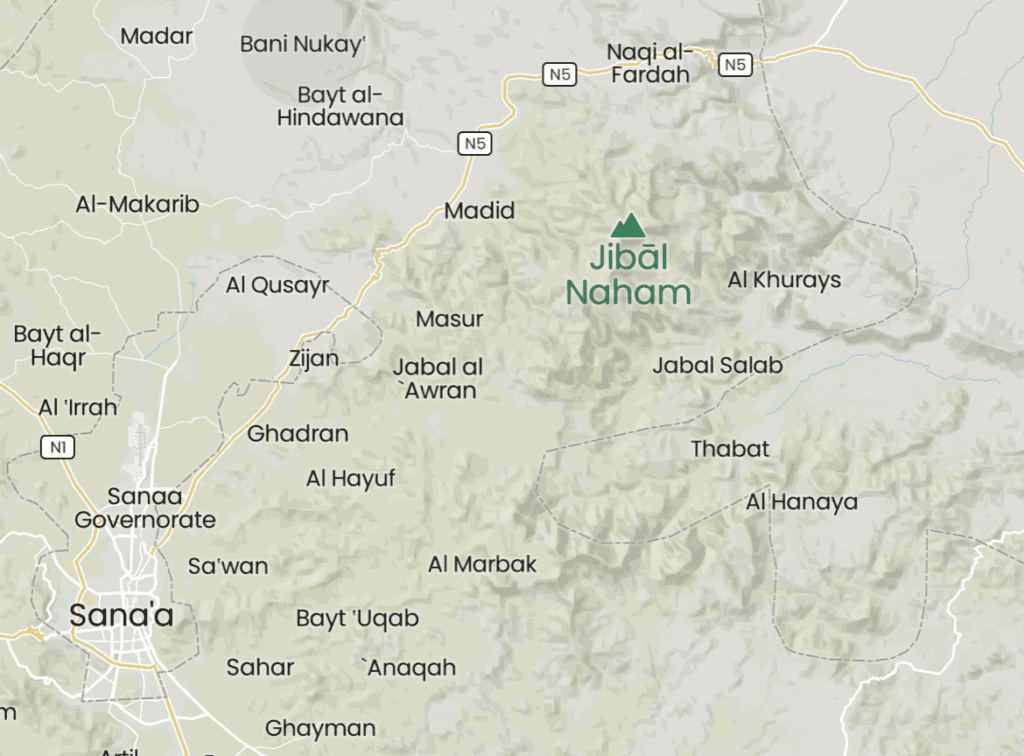

The modern Nihm tribe is located west of Marib and north of Sana’a. As you can see at Mapcarta.com, the tribal name is also used to describe places including the District of Nihm and Furdat Nihm (the village of Nihm). There is also a mountain known as Jibal (Jabal) Naham/Nihm. MapCarta also shows “Naham” as a “a tribal area in Yemen” in roughly the same region as the District of Nihm, where “Naham” is probably just another transliteration of Nihm, perhaps capturing one particular dialect. Naham is said to also be known as Belad/Bilad Nehm (the land of Nehm), Bilad Nahm, Nahm, Nehm, and Nihm, etc.

Of course, modern maps don’t necessarily tell us that the NHM name was in Yemen in 600 B.C., which is why it’s so fascinating that we now have archaeological evidence showing that a prominent man from the NHM tribe was in the region around the 7th century B.C. Many other inscriptions confirm the existence of NHM in the region over the centuries. The persistence of that name in a small part of the world across so many centuries is fascinating. Even if Joseph Smith had been so lucky as to see Nehem on a map and managed to pick that obscure, minor spot to somehow add “local color” and “evidence” to his tale — evidence that he would never use and nobody would even notice until about 150 years later — it would have been unlikely that the obscure name he plucked off a modern map would be so fortunate as to come with later archaeological evidence that it was there and in use in 600 B.C., not just the right name, but a place whose significance would be magnified by surprising finds that would give remarkable plausibility to the “impossible” places of the River Laman to the north and Bountiful directly to the east.

For critics, however, “proof” of the insignificance of Nahom is easy to propose, but must also bear some scrutiny before one blindly accepts it. Silly efforts to negate the import of Nahom by finding related names for, say, a tidal creek in Tanzania or a twentieth-century kibbutz in Israel are simply irrelevant (see my report, “Noham, that’s not history“). Theories that Joseph got all he needed to fabricate the story of Lehi’s Trail by looking at some rare European maps of Arabia fail in numerous ways (see my article, “Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dream Map: Part 2 of 2” in Interpreter, as well as Part 1, where I examine other objections as well). Ill-informed claims that there is no evidence for the name NHM in Lehi’s day or that the Book of Mormon name “Nahom” can have no relation to the South Arabic NHM are easily refuted and should have no impact on people familiar with the most rudimentary aspects of the Arabian Peninsula evidence — see, for example, Neal Rappleye and Stephen O. Smoot, “Book of Mormon Minimalists and the NHM Inscriptions: A Response to Dan Vogel,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 8 (2014): 157-185.

However, a seemingly more plausible approach for dowplaying Nahom involves noting what the evidence doesn’t establish. So while we we have evidence of a Nahom-like tribal name around 700 BC plausibly near the Nehem on several maps and near modern Nihm tribal lands (the construction of the temple at Marib was a very big deal by a very powerful and wealthy tribe, making it quite plausible that luminaries from other tribes in the region would want to be involved), all that really tells us, supposedly, is that the tribal name was in the area, not a place called Nahom. It’s just a tribal name, not a place name, and so believers in the Book of Mormon have nothing of interest in the archaeological finds. Nothing to see, folks, let’s move along. As one commenter put it in responding to my post, “What to Make of ‘Plagiarism’ of the Bible in a Purportedly Ancient Text? A Jewish Scholar Offers a Thoughtful Perspective“:

The altar does NOT have Nehem written on it. Objectively false. An altar was found. And it has ancient writings believed to resemble the English sounds N H M. But this refers to a family/tribe, not a physical place.

This is a rather weak argument. The inscriptions are in a well-understood script that clearly should be transliterated as NHM, even though the H would be pronounced differently than our H. It’s not something that somebody somehow “believes” might “resemble” the sounds N H M. There is no question that the NHM on the altar refers to a tribal name that today is often written as Nihm, but at various times has been written as Nehem, Nehhm, etc., and could be related to Nahom in the Book of Mormon. Sure, the altar does not have “Nehem” in the Roman alphabet written on it, but it’s clutching at straws to say it doesn’t have Nehem (or Nihm) on it. The NHM word, written without vowels, can be expressed as Nihm or even Nehem, as we see on some old maps.

A similar argument has been made by others with more substance. In fact, we have one apparently Latter-day Saint scholar of unknown identity, known merely as “RT,” stating in an article for Faith Promoting Rumor that tribal names did not get used anciently as place names in Yemen, and that Nephi’s calling Nahom a “place” is simply wrong and confused. While RT must admit that the Nihm name today appears to describe both a region and a tribe, and that forms of that name literally appear on multiple maps, he argues that we can’t project (or rather, “retroject”) this modern feature of Nehem/Nihm back into Lehi’s day. To his credit, he fortifies the argument by citing personal correspondence with a noted scholar familiar with Yemen who is quoted as saying that tribal names simply were not used as place names. The resulting argument sounds rather impressive:

Nahom is inaccurately portrayed as a place rather than a tribal people. We mentioned at the beginning of this study that a critical assumption made by BoM researchers about Nahom is that it represents a designation for the territory possessed by the tribe Nihm, which is why the narrative speaks of Nahom as a place rather than a people. As explained by [Kent] Brown, “Naturally, a person reasonably assumes that, if the majority of the NHM tribe dwelt in a certain area, they would have had a ‘place’ for themselves that bore their tribal name. And outsiders would have known it.” [citing Brown’s “On Nahom”] So on this understanding, there were actually two closely interrelated usages of the root NHM as an appellative in ancient south Arabian culture, one used to denominate the tribal group itself (the people Nihm) and another to refer to its territory (the Nihm region), a conclusion that finds support in the modern use of the term Nihm to designate a tribe as well as a geographical district in present day Yemen. However, it is doubtful that this later use of tribal names to refer to geographical entities can be retrojected onto much earlier periods and careful examination of South Arabian inscriptions indicates that the names of tribes were essentially social-political in orientation. Christian Robin, one of the world’s foremost experts on the tribal history of ancient South Arabia, explains that the tribal names “are not toponyms nor ancestor names. But they were used as eponyms when the genealogies were elaborated in late Antiquity and early Islam… The tribes in the south are strictly connected with a territory. But, in general, there is no confusion. The inscriptions distinguish always between Ḥimyar [a south Arabian tribe] and ‘the Land of Ḥimyar’.” [citing personal communication with Dr. Robin, 2015] Accordingly, within an ancient south Arabian context, it does not make sense to speak of Nihm as though it were a regular place name.

Source: RT, “Nahom and Lehi’s Journey through Arabia: A Historical Perspective, Part 2,” Faith Promoting Rumor (a blog at Patheos.com), Oct. 6, 2015, tinyurl.com/RT388912.

This seems compelling until you realize that Robin’s argument, as conveyed by RT, is that ancient inscriptions don’t treat the tribal name as a place name by itself, but tend to associate the intended physical place with additional language coupled with the tribal name as in “the land of Nihm” instead of just treating the name Nihm as a stand-alone place name like Disney World that needs no further geographical indicators. But does that tendency really support RT’s claim that it would make no sense for Nephi or any other visitor to what may have been formally known as “the land of Nihm” (or a kingdom, region, village, mountain, valley, etc., of Nihm) to later say that they had stayed in the “place that was called Nahom”? What Nephi wrote can be completely consistent with Nihm being a tribal name that was also associated with a physical place, wherein additional verbiage was needed to distinguish the tribe from the place. In this case, such additional language is evident in “the place that was called Nahom.”

But there’s still a problem with Robin’s argument that needs some attention.

Robin’s Nuanced Distinction Between Tribal Names and Place Names

While we don’t have access to what Robin told RT, but we do have access to what Robin has published, and there we learn of a potentially relevant example that further undermines RT’s stance.

Christian Robin is a co-author of a chapter in a beautiful and information-packed book on Yemen that I’m proud to own: Yemen: 3000 Years of Art and Civilisation in Arabia Felix, edited by Werner Daum (Innsbruck: Pinguin and Frankfurt am Main: Umschau Verlag, 1987). The chapter is “Towns and Temples — The Emergence of South Arabian Civilization” by Remy Audouin, Jean-Francois Berton, and Christian Robin, pp. 63-77. (The text alone of this chapter is available online, archived from Yemenweb.com.) On page 63, Robin refers to the ancient name Ma’in, which, according to an ancient South Arabian inscription in Yemen, is a tribal name that also looks like it was treated as a place:

But trade seems to have grown significantly only between the 8th and the 6th centuries B.C. The South Arabian inscriptions only rarely mention this trade, and even when they do, it is in parenthesis. An inscription (about 4th/3rd century B.C.) on a straight section of the city wall of Baraqish runs like this:

Ammisadiq … and Sa’id …, leaders of caravans, and the Minean caravans who had set off in order to trade with them in Egypt, Syria and beyond the river…, at the time when ‘Athtar dhu-Qabd, Wadd and Nakrah protected them and their property and warned them of the attacks which Saba’ and Khawlan had planned against their persons, their property and their animals, when they were on their way between Ma’in and Rajma (= Nagran), and of the war which was raging between north and south…. [emphasis mine]

Ma’in in this passage looks like it is a place, as is Rajma (= Najran on modern maps). An ancient inscription on a city wall spoke of people traveling between Ma’in and Rajma. The authors of this chapter speak of Ma’in several times as if it were a specific place in ancient times. It’s still a place, a city, today. Regarding Main/Ma’in as a place, see “Kingdom of Awsan” at Wikipedia and see Wikipedia‘s article on the Minaeans, which refers to the region that would become known as Ma’in (a place). But Ma’in is also a tribe, a well-known point made explicit on p. 63 shortly after the passage cited above, when the authors speak of “the small caravanning tribe of Ma’in.” Robin and his co-authors appear to be speaking of Ma’in as both a place and a tribe. Doesn’t that directly contradict RT’s argument? Puzzled, I reached out to Robin myself via Academia.edu, who kindly answered my inquiry about Ma’in apparently being a place as well as a tribe. He explained that, “In [the phrase] ‘between Main and Rajma,’ the first is attested only as tribe name; the second is apparently a town name” (personal correspondence, 2016).

So apparently, though the translation of the inscription makes it sound like Ma’in is a place, a more nuanced understanding is that Ma’in is a tribe name only. Thus, in speaking of going to or from Ma’in, what is meant is the place of the tribe Ma’in, not just Ma’in. A more nuanced translation, then, might speak of the place of the Ma’in tribe or perhaps “the place that is called after the name of the Ma’in tribe.” Confusing Ma’in for an actual place name was apparently a rookie mistake I made, the kind of mistake that a newcomer to the nuanced inscriptions of Yemeni tribes can easily make, and, I might add, the kind of mistake that the ancient newcomer Nephi could have made as well. Or perhaps he just wasn’t interested in taking up more space on the small plates for a fully nuanced description of “the place that is called the land of Nahom” or “the place of the tribe called Nahom,” but perhaps his newbie shortcut of “place that was called Nahom” was, frankly, nuanced enough. This was not as sloppy as talking about going between Ma’in and Rajma/Najran, as we see in one inscription and its translation, but it may not be completely satisfying for those who demand high precision in their ancient texts.

Robin’s 1987 chapter that quotes the Baraqish wall inscription does not give a footnote with details of the inscription, but with a little searching I found it on an excellent resource for South Arabian inscriptions, the Corpus of South Arabian Inscriptions (CSAI), part of DASI (Digital Archive for the Study of Pre-Islamic Arabian Inscriptions), a project directed by Alessandra Avanzini of the University of Pisa. At CSAI, you can find the Baraqish wall inscription listed as “M 247 RES 3022; B-M 257.” It is in the Central Minaic dialect of Ancient South Arabian. You can see the inscription, its transliteration, and two translations. The translation from CSAI for verse 2 speaks of “the hostilities which Saba’ and Hwln brought against them and their goods and their camels, on the route between Ma’in and Rgmtm….” A translation by Walter Mueller speaks of the “Karawanenstrasse zwischen Ma’in und Rgmtm” (“the caravan trail between Ma’in and Rgmtm”). The transliteration includes the phrase “byn M’n w-Rgmtm” which I think means “going from/between Ma’in and Rgmtm” based on the meaning of byn. The link is to Joel A. A. Ajayi, A Biblical Theology of Gerassapience (New York: Peter Lang, 2010), p. 59.

Incidentally, Baraqish, the site of the inscription mentioning Ma’in as if it were a place, is in the Wadi Jawf and is associated with the modern Nihm tribe, as Neal Rappleye observes in his excellent article, “An Ishmael Buried Near Nahom,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 48 (2021): 33-48.

Dr. Robin, in his kind response to me, also added a valuable clarification regarding the alleged impossibility of tribal names also being place names:

Normally the categories “territory” (country) and “population” (tribe) are distinguished. But, in Yemen (and perhaps in Eastern and Northern Arabia) on the borders of the desert, there are some instances of proper names used as a tribe name and also a town name (like Sirwah and Najran). [personal correspondence via Academia.edu, 2016, emphasis mine]

In this process, then, we have learned that scholars of Yemen like Christian Robin can casually translate an ancient inscription in a way that seems to treat a tribal name as a place name, and that in spite of saying tribal names aren’t place names, recognize that there are cases when they are, as with the places Sirwah and Najran, both not far from the place/land/region of Nihm. So Nihm/Nahom/Nehem/NHM as an actual place name is not actually ruled out, though Robin in his note to me went on to say that he felt it would be “unlikely” for Nihm to be a pre-Islamic place name, for anciently it was just a tribal name. A tribe, of course, that is associated with a particular place. For a traveler coming to the place or the land of the tribe of Nihm/Nehem, referring to it as “the place that was called Nahom” seems undeserving of objection. Let’s give Nephi a break on this one.

A Key to Understanding the Connection Between Yemeni Tribal Names and the Names of their Territory

A simpler way of dealing with the argument that a tribal name like NHM cannot be a place name is to consider how other scholars look at the relationship between tribal names and place names. While Robin as cited above already hinted at a link between tribal names and place names when he said, “The tribes in the south are strictly connected with a territory,” we get another perspective in a work on northern Yemen. Barak A. Salmoni, Bryce Loidolt, and Madeleine Wells in Regime and Periphery in Northern Yemen: The Huthi Phenomenon (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corp., 2010), p. 47:

A second characteristic relatively unique to Yemeni tribalism is the strong identification of tribe with place. Unlike tribes in parts of Africa or other areas in the Middle East, north Yemeni tribes do not have a tradition of transhumance, nor is a Bedouin nomadism a social value in tribal collective memories. As sedentary agriculturalists, therefore, Yemeni qaba’il [tribes] exhibit a particularly strong attachment to and identification with “their” territories. This identification is illustrated by the Yemeni highlands proverb, “izz al-qabili biladah — the pride/prestige of a qabila [tribe] is [in] his land” and informs the local geographic imagination. Place names and tribe names become nearly identical, such that even people of unrelated families living in an area are often assimilated to the same tribe over a few generations and named in terms of the preexisting local place name or the demographically dominant grouping in the area. [emphasis added]

Granted, this does not necessarily apply to ancient Yemen, but it raises a presumption that seems consistent with some information already presented regarding ancient Yemen which should be considered as we review some additional examples.

Turning again to the chapter “Towns and Temples — The Emergence of South Arabian Civilization” by Remy Audouin, Jean-Francois Berton, and Christian Robin in Yemen: 3000 Years of Art and Civilisation in Arabia Felix, we have another ancient example to consider:

Two degrees of dependence can be observed: some tribes were vassals of the Sabeans, almost in a state of slavery. Tribes in that situation would lose their political independence along with their religious freedom. This state of affairs would be symbolised by the destruction of their royal palace and the dismantling of their main secular and religious inscriptions. Others were only subjected to a protective rule: a tribe in that situation retained its own institutions and pantheon. At its head the tribe had its ruler, who represented his people, and who was given the title of “King”. In spite of retaining its own pantheon the tribe acknowledged Sabean rule, in particular by worshipping the Sabean main deity Almaqah. In Karib II’s list of such tribes he simply mentions their names and those of their kings; the names of their deities are not included. Such tribes, too, had to pay tribute, which might be in the form of cattle, or sometimes, perhaps partly, be paid through the erection of a public building. Thus the king of Kaminahu (present day Kamna) in Nashq (now al-Bayda) built two towers of the city wall “for Almaqah, the kings of Marib and Saba”. (p.

There is a king of Kaminahu, as if it were a kingdom, but Kaminahu is also a tribe, as is again mentioned on p. 76, followed by a reference to “several principalities or kingdoms” that had existed anciently, “e.g., Haram or Kaminahu.” So Kamimahu is the name of a tribe and a kingdom, and a kingdom, of course, tends to have a physical domain. It would seem that the authors, Robin included, see Kaminahu as more than just a tribal name alone, but a name that might very well be viewed to newcomers, at least, as a place that was called Kaminahu.

Wikipedia’s article “Kaminahu” also sees Kaminahu as an ancient place:

Kaminahu (Arabic: مملكة كمنه; Old South Arabic: 𐩫𐩣𐩬𐩠𐩥 kmnhw; modern Kamna) is the name of an ancient South Arabian city in the northern al-Jawf region of present day Yemen, 107 km north-east of Sana’a at about 1100 meters above sea level.

In early times Kaminahu like other towns in al-Jawf such as Ḥaram and Nashan, was an independent city state.

But perhaps we can’t trust Wikipedia on this matter. We need a more nuanced approached from those who can tell when something that looks like a place name really isn’t. What do scholars familiar with ancient inscriptions from Yemen say of Kaminahu? Let’s turn again to CSAI for some insight. On the CSAI page for the site Kamna, we read:

This site is located in the middle valley of the Jawf, 107 km north-west of Maʾrib, 9 km west of al-Ḥazm, on the left bank of wādī Madhāb, north-east of as-Sawdāʾ, ancient Nashshān.

Toponymy

The name Kaminahū (Kmnhw) used to indicate at the same time a tribe, its territory and probably also its ancient capital-city, today called Kamna. For the identification of the ancient toponym: Halévy 1873: 602-603; D. H. von Müller (1880: 1004-1005); Robin 1992: 155….Chronology

The occupation of the site is dated to the 8th century BC at the latest (Kamna 1, Kamna 13+14). If we consider that the basis of the rampart lies on anthropogenic accumulation layers, and that the rampart dates back to the 7th century BC, the site foundation may precede the 8th century BC.

Kmnhw was the seat of an autonomous and independent political entity in the 8th-6th centuries BC, and at the end of the 1st millennium BC. The Madhābian language was spoken. The tribe had its own pantheon. In the 8th century BC, Kmnhw appeared as one of the most important political entities in the Jawf valley together with Nashshān, upon which it eventually imposed itself until, supported by the Sabaean ally, Nashshān finally stated its domination by force upon Kmnhw.

Kmnhw became an ally of the Sabaean mukarrib Krbʾl Wtr bn Ḏmrʿly. This alliance quickly took the appearance of a vassalage relationship under which Kmnhw paid tribute to the Sabaean kings (CIH 377).

With the decline, and then the disappearance of the kingdom of Maʿīn, Kmnhw flourished once again in the 2nd-1st century BC.

Here we have a prominent tribe that is quite close to region of the Nihm tribe, west of Marib and north of Sana’a in the Wadi Jawf region, in existence in Nephi’s day. Its name was “used to indicate at the same time a tribe, its territory and probably also its ancient capital-city, today called Kamna.” If that could happen for the name of the tribe Kaminahu, why not for the name of what may have been a near neighbor then, the Nihm tribe? Surely this evidence should alleviate any hyper-sensitive concerns about “retrojecting” modern practices in Yemen back to Nephi’s day. The NHM tribal name, whether written as Nehem, Nehhm, or Nihm, can refer to a place and a tribe in modern times, and there’s no reason to think that this could not happen in Yemen, or at least in in Wadi Jawf in northern Yemen, when Nephi came to the place called NHM, appropriately transliterated into the more Hebrew-like Nahom, possibly packed with a Hebrew word play related to the meaning of mourning or murmuring that nicely fits the context of 1 Nephi 16:14. No retrojection there, but that won’t stop the unnecessary rejection of the evidence Nahom brings.

There are other tribes we could consider, such as the tribe of Haram whose name, per Wikipedia’s article on Haram (Yemen) is also given to “an ancient city in the north of al-Jawf in modern-day Yemen, at about 1100 metres above sea level. It is bordered by the Yemen Highlands to the north, in the west by the ancient Kaminahu (present day Kamna), in the east by the ancient Qarnāwu (modern Ma’īn) and in the south by the Ghayl.” This is also in the region of Nahom, and joins its neighbors Kamainahu and Ma’in in having names that either clearly were or appear to have been used as place names. On the CSAI list of site, Haram is listed as “Hrm” on a page stating that “The site of Kharibat Hamdān or Kharibat ʾl ʿAlī is the current name of the ancient Haram. Haram in antiquity indicated the name of the site as well as the name of the tribe who resided there, together with the surrounding territory. The site still bore the name of Madīnat Haram in the 1940s.”

We could also mention the very large region of the Hadhramaut, with a name that describes both a tribe and the land, or Haram, which is an ancient city and a tribe (also mentioned above). And there is more to say about the Himyar people, whose name is used to refer to a tribe, the territory of the tribe, and a kingdom, as we read in Yosef Yuval Tobi, “Ḥimyar, kingdom of,” Oxford Classical Dictionary, Aug. 22, 2017:

The Rise of the Kingdom of Ḥimyar, c. 110 BCE–4th Century CE

According to Yemeni genealogical writings, the kingdom of Ḥimyar is named after its founding father, Ḥimyar the son of Saba.’ The name, however, is also widely used to represent a tribe by that name, or a confederation (shaʻb) of ancient South Arabian tribes. The territory of this tribe has also come to be known by the eponym of Ḥimyar, whose center was in the mountainous district of Yāfiʻ, in the southeast of Yemen, near Abyan, the delta of wādi Banā’, whose waters empty into the Indian Ocean, near the port city of Shuqrah (Map 1).

Likewise, in Glen W. Bowersock’s excellent “The Rise and Fall of a Jewish Kingdom in Arabia,” Institute for Advanced Study, 2011, we see the tribal name Himyar used to indicate a territory and a kingdom, not just the tribe.

I should also mention that the scholars at CSAI use “Nihm” as a geographical region when categorizing the location of inscriptions in their database. You can see several sites listed under the region “Nihm” on, for example, a page listing sites beginning with “b” at CSAI. But I believe this listing is refers to modern geographical regions, not the ancient sites. Several of the ancient sites listed on the CSAI website have already been mentioned above, and there may be more since I’ve only examined a handful. One that I did not mention above relates again to Ma’in, whose CSAI site page shows that the tribal name Ma’in is also a geographical site, with the text speaking of Ma’in as a geographical place and city. I’ve only looked at a handful of the sites at CSAI, so there may be others of interest.

But let’s now look at how other modern scholars view NHM with some help from Neal Rappleye.

Further Insights from Neal Rappleye

As I was preparing this post, I was delighted to watch an excellent presentation, at the 2022 FAIR Conference,”Ishmael and Nahom in Ancient Inscriptions” by Neal Rappleye, Aug. 3, 2022. I noted that several of his slides quoted scholars discussing the ancient NHM name in a way that recognized that there was a place associated with that name. For example, in St. John Simpson, ed., Queen of Sheba: Treasures from Ancient Yemen (London: British Museum, 2002), 166-167, we read this basic statement of the NHM name on the altars from Marib:

The dedicant Bi’athtar, who comes from the Nihm region, west of Marib, dedicated the female person Fari’at to the god Almaqah, presumably to serve in the temple employment. [emphasis added]

There was a Nihm region, not just a Nihm tribe, and it was in the area, west of Marib. That’s not very significant, perhaps, but this is a reminder to the “NHM minimalists” who want to see NHM as just three letters on an alter, forgetting that it tells us something about a name associated with a tribe and their region or land.

Rappleye also cites a German scholar, Hermann von Wissmann, Zur Geschichte und Landeskunde von Alt-Südarabien, Sammlung Eduard Glaser III (Vienna: Der Öserreichischen Akadaemie der Wissenchaften, 1964), with two passages that you can readily see on Google Books:

[D]ie Grabinschrift CIH 969, mag auch ins südliche Nihm zu stellen sein, da die Weinrankenverzierung eher aus einem Hochland stammt. (p. 97)

CIH 969 stammt wohl aus dem Land Nihm, dem südlichen Nihm. Es ist Grabinschrift und Beginnt: Bildnis des MTWB aus Nihm (NHMYN).” (p. 307)

In the first passage, von Wissmann speaks of the site of a particular inscription likely being “in southern Nihm,” as if Nihm were a place. In the second passage, he again speaks of “southern Nihm” but also mentions “the land Nihm.” Again, he indicates that the name Nihm can refer to a physical place. This is in the context of ancient inscriptions and their locations.

Rappleye also shows a map of apparently ancient locations in Yemen from Peter Stein, Die altsüdarabischen Minuskelinschriften auf Holzstäbchen aus der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek in München, 2 vols. (Tübingen and Berlin: Ernst Wasmuth Verlag, 2010), 1:23, fig. 1, which has a place labeled as NHM (Nihm):

At the end of his presentation, Neal answered a question from me, sent by text, about the issue of NHM just being a tribal name. He indicated that he has been looking at the issue and has found a variety of sources that shed more light on the question, and will be preparing something in the future. I look forward to his paper!

Conclusion

Finding a candidate for the place Nahom on an 18th century map was interesting, raising the possibility of evidence related to the place Nahom in the Book of Mormon. This became much more interesting in the 1990s when a German archaeological team unearthed three beautiful altars at a temple in Marib that were donated by a prominent member of the NHM (Nihm) tribe, confirming that the NHM name was in the area around 700 BC. Coupled with the growing evidence supporting the plausibility of other once “ridiculous” details in the story of Lehi’s Trail, we now have complex of evidences from the Arabian Peninsula that make it implausible that Joseph Smith or his US-based technical advisory team could have concocted the details given for Lehi’s Trail based on information available to them or almost anyone at the time.

Whoever provided the details related to the River Laman, the place Bountiful, and the place that unspecified others (perhaps fellow Israelites from the Northern Kingdom dwelling in the Land of Nihm?) told them was called Nahom must have had knowledge of these locations based on actual on-site experience in the Arabian Peninsula. Whether it was most likely Nephi or, say, Sidney Rigdon or one of Joseph’s adventuresome neighbors, is left for readers of the Book of Mormon to ponder. Or maybe Joseph was just incredibly lucky, making very wise and improbable guesses with the help of rare maps that he likely never came close to. While there is still much to learn, there is already much to appreciate and no reason to assume that unfair “retrojection” is involved in seeing “the place that was called Nahom” as a plausible place related to real names and locations in ancient Yemen.

Neal Rappleye, Stephen Smooth, Jeff Lindsay, et. al, are like little childen staring up at the clouds convincing each other they see the coulds form the same shapes and then self-declaring these shapes as “complex evidence” of some invisible hand modling their imagined forms. Their non-doctrinal beliefs do nothing but mock and ridicule our Church, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. As Latter-day Saints all we can do is inform the world they do not represent our Church. Such Bible code style (which curoiusly also relies on missing vowels and vowel morphing) connection fabrication is not something our Church encourages or considers faith promoting. Quite the opposite.

Andrew is a student of the area in quesiton, fluent arabic speaker, and actually visited many of the sites in quesiton as a Latter-day Saint. Andrew offered patient, mature, and extremly rational retorts to Neal Rappleye, Stephen Smooth, and Jeff. Incapable of rejoinding, all Jeff can do is censor Andrew.

“All Jeff can do is censor Andrew.”

Stephen, I have not received any notifications of comments from Andrew. You have posted some things quoting him without any censorship. Perhaps there’s a problem with what he enters as far as the Askimet spam-blocker goes, but I’m not rejecting anything from Andrew.

It seems you are claiming to be a member of the Church. Is that correct? Why so uptight about the existence of evidence from the Arabian Peninsula for the plausibility of Lehi’s Trail? How does believe in the historicity of the Book of Mormon “mock and ridicule our Church”?

You see, there you go again. As for your yet another strawman, no one claimed believe in the historicity of the Book of Mormon is ridicule. But sense you bring it up, the Church does not claim the BoM is to be use as a historical document. In fact, the BoM claims it is related to Spiritual matters.

Jeff, why are so uptight with members who have the integrity and refuse to bow down to you but rather follow the Spirit? That is not a strawman, for you have have equated of your connection fabrication as evidence and those who have the integrity to standup to such nonsense as uptight?

Stephan, this is why I’m not convinced you are a member of the Church who has been studying the Book of Mormon and paying attention to what the Church teaches. The Church absolutely affirms the authenticity of the Book of Mormon as an ancient sacred record written by genuine ancient prophets of God. If you go to the Church’s website and search for “Book of Mormon authenticity” or “historical authenticity of the Book of Mormon,” you will find page after page showing that the Church is serious about the ancient origins of the text.

One of those pages in the top ten results for both searches is the Gospel Topics essay, “Book of Mormon and DNA Studies.” It begins with this:

It then goes on to explain why the DNA evidence does not disprove the historic authenticity of the record.

This essay does, however, correctly point out that “the primary purpose of the Book of Mormon is more spiritual than historical.” It was not written to serve as a detailed historical guide to the Nephite people, but was written to help us in our day as a tool to testify of and bring us to Christ, using excerpts and summaries of writings from historical people and descriptions of historical events, such as the visit of Christ to the Americas after His resurrection, to serve its spiritual ends. But the spiritual purposes of the book do not mean that we do not adamantly insist that the book is authentic, ancient, and historical. There was a Lehi and a Nephi, they did travel through Arabia, and the places they describe are real, even if we don’t know where they were.

The Church continues to emphasize the Book of Mormon as sacred scripture. In its online introduction to the Book of Mormon, it declares: “The Book of Mormon is a volume of holy scripture comparable to the Bible. It is a record of God’s dealings with ancient inhabitants of the Americas and contains the fulness of the everlasting gospel.” It then cites the testimony of multiple witnesses confirming that it was translated from genuine ancient gold plates through the power of God. This is not inspired fiction. The Church affirms that it is rooted in reality, with tangible ancient gold plates containing real engravings in a real language about real people and events written by real prophets — at least one of whom is now a real resurrected being, the Angel Moroni, seen by multiple witnesses. Don’t overlook just how serious the Church and its faithful members are about the reality of the Book of Mormon.

There you go again with your strawmen. I never said the things you are implying I said. But of course you know that, goes to your usual lack of integrity.

The ultimate anti-Mormon Jeff Lindsay. If our prophet Russell M. Nelson wanted to direct my Stake President to ex-communicate me the way you ex-communicate me, he would. Your virulent disagreement with President Nelson’s decision not excommunicate those who call you out for connection fabrication is the ultimate anti-Mormon position. Because I am a member of the Church, I know you know there is no requirement to accept your Nahom theories to be a member no matter how much spirit of contention spurs in you.

Bullies like Jeff name called me “uptight” when I questioned “principal ancestors” and then with the passage of time my supposed uptightness was suddenly insightful.

A lot of faithful people, myself included, recognized the need to update the assumptions behind Bruce R. McConkie’s statement that the Book of Mormon described the principal ancestors of all Native Americans. So asking questions and pointing out errant assumptions is a positive thing in general, and it seems that you feel that’s what you are doing here. OK, well, thanks for that, but can you help me understand why you feel I am an anti-Mormon in pointing out evidence that is consistent with the authenticity of the Book of Mormon?

“can you help me understand why you feel I am an anti-Mormon in pointing out evidence that is consistent with the authenticity of the Book of Mormon?”

I don’t. I know you are anti-Mormon according to your usage the word. Your agenda of bashing the prophet for not excommunicating Latter-day Saints like me and of hating on us makes you anti-Mormon.

Please quit throwing a single individual (Bruce R, McConkie) under the bus for a widespread belief that pre-dated him and he only codified and articulated. To help you understand, from Ether to Moroni there was a widespread believe in a global flood, not just Moroni. Such widespread believes are exactly why the Church focuses on spiritual aspects of the Book of Mormon and not its historicity. Does your rejection of the global flood make you anti-Mormon? I suppose it depends if we are using the word consistently and not just when you have an agenda. Could a person accusing fellow Latter-day Saints of being anti-Mormon because they openly question seashells on mountain tops as “evidence” of a global flood and openly criticize the leadership for not excommunicating those people be consider anti-Mormon? If you are using the word consistently, yes.

Stephan, after multiple insults, if you are now also accusing me of hate and bullying for disagreeing with you, then I’m afraid you need to focus your efforts elsewhere and get your own blog where you can express your opposition.

If any of you seriously think that the evidence from the Arabian Peninsula is contrary to the Church’s views of the Book of Mormon, you may wish to consider the Church’s own Book of Mormon Student Manual and its treatment of 1 Nephi 16. There you will note two interesting sections. First this passage on Nahom and the archaeological evidence that such a place existed anciently in the Arabian Peninsula (though much more could have been said about its location and the plausibility of the general routes to and from Nahom):

And then there is this passage on Bountiful, which draws upon the work of Warren Aston and does includes its eastward location from Nahom:

The Student Manual then displays a map showing Lehi’s Trail, showing a path very similar to the route proposed by Warren Aston. That map is also reproduced on page 410 of the manual in the Appendix. The map comes is adapted from the map provided in Daniel H. Ludlow, ed., Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 5 vols. (1992), 1:144.

So if someone claims that the leaders of the Church reject the work of Aston and others in identifying specific candidates for the places mentioned in the Book of Mormon, or that such work undermines the Church and is contrary to its positions, I would suggest that there is no reason to take that person seriously.

“if someone claims that the leaders of the Church reject the work of Aston “

Obviously, no one has said that, as Jeff knows. As Jeff knows, what they have said is Aston’s unofficial opinions are no more official than what Jeff calls McConkie’s opinion printed not in a student manual but in official canon. Or the official historicity opinions, though rejected by Jeff, of Ether thru Moroni regarding a global flood. Promoting unofficial opinions as if they were doctrine undermines the Church. Criticizing the prophet for not excommunicating those who disagree with Jeff is anti-Mormon.

So by Jeff’s own standard, Jeff should not be taken seriously. Just a fact. Jeff’s inconsistent and contradictory reasoning grows with every passing year and he can no longer standard up to scrutiny and he rejects genuine dialogue by censoring and blocking.

What? I’ve never said that Aston’s positions are official positions of the Church, or that disagreeing makes one an unworthy member. In pointing out the bad logic and questionable claims of a troll or even a believer who disagrees with Aston on the basis of questionable positions, I’m critiquing the argument of an individual, not their membership status or faith in God.

While the Church boldly affirms the reality and antiquity of the Book of Mormon, the details of the relationship between archaeology and the Book of Mormon is generally not a matter that the Church takes any positions on, even though the Church’s own Book of Mormon Student Manual cites Aston’s work favorably.

Latter-day Saints are free to propose other routes for Lehi’s trail or other question whether any proposed candidates for the places there adequately match the text. But the arguments Stephan and others have raised against a connection between Nahom and Nehem on Arabian maps and the tribal lands of the ancient Nihm tribe are not intellectually sound, IMO. Those connections remain worthy of consideration and may well be taken as potential evidence for the plausibility of the Book of Mormon, especially in light of Nahom’s relationship to the excellent candidates that have been discovered for Bountiful, Shazer, and the River Laman and Valley of Lemuel. The fit of the Arabian data to the details in the Book of Mormon should be worthy of deep contemplation, not reflexive rejection.

What? Stephan never claimed to make an intellectually sound argument against Nahom Connection. He suggested the connection itself was not intellectually sound.

Those who find the connection intellectually sound are not only in a super, super minority, but belong to a school of Kabalistic Mormon thought demanding predetermined conclusions blinding them to a rational discussing regarding connection making. A fact seen in your constant vacillation of position. You just switched again from “evidence” back to “may well be taken as potential evidence for the plausibility’“. May-well-be-taken, potential, plausible … back to words of massive subjective doubt. Those words do not imply “worthy of consideration” in the slightest, in fact, just the opposite. In a world where there is only 24 hours in a day, those words suggest a broken clock where the effort to figure out the two times it is right is far greater than the value extracted in knowing. Unless the individual figuring it out has some escalating investment in desperate need of validation.

Fact is Jeff, you bashed the prophet for not ex-communicating Stephan, merely because Stephan disagreed with you. The comment this is one is in reply to is more of a weasel than it is a way of asking for forgiveness.

Andrew replies:

Getting back to the meat of the discussion. I’d love to hear more about this argument that the Nephites didn’t travel along the coast. How is that reconciled with the text which specifically says they did?

“And we did go forth again in the wilderness, following the same direction, keeping in the most fertile parts of the wilderness, which were in the borders near the Red Sea.”

How does that description fit with travelling 140 or so miles inland on the complete opposite side of a mountain range?

Either way I’m still not sure how this solves the problems I pointed out. Nehem still is in the mountains. BOM doesn’t describe them moving across the mountains. Why would they enter Nehem at all? If they were traveling along the famous incense trail, that would have been east of Nehem, so they would have had to go west over the mountains to get to Nehem. And again, the burial sites referenced with the inscriptions aren’t in Nehem.

The video makes some very specific claims. I’m just going to quote the narrator directly.

“…a team of German archaeologists found an ancient altar in southwestern Arabia with the name of a local tribal region inscribed on its side. That name, Nehem.”

This isn’t true. Objectively false. An altar was found. And it has ancient writings believed to resemble the English sounds N H M. But this refers to a family/tribe, not a physical place. And it’s not known that this tribal name matches with the Nehem place name. In the video a whole bunch of liberties are being taken to correlate data for which no relationship has actually been established.

“This altar, which dates back to about 800 BC”

This is in dispute, a dubious claim. But video presents it as factual.

“And its [the altar] location is exactly where you’d expect it to be…” (And at this point the map in background shows line going to Nahom.)

No, it’s not exactly where you’d expect it to be.

For starters, the altar, which is what the narrator is specifically talking about, IS NOT IN NEHEM!!! The altar is at a burial site which is not in Nehem. The video is straight up lying. And as I’ve also pointed out, “where you’d expect it to be” is also in dispute re the text of BOM. BOM says they were at the coast, not 140 miles inland.

“Additionally, Nehem was one of the largest burial areas in ancient Arabia, making it a natural location for Ishmael’s burial”

As stated, no it wasn’t. Nehem had nothing to do with the burial sites referenced and was not itself a “burial area.”

What do burial sites have to do with the Book of Mormon anyway? Oh, because Ishmael is buried in Nahom? So you’re saying Nehem is a special location in Yemen where everybody gets buried? Everybody comes from afar to bury in this special site? So, duh, it’s a “natural location.” Let’s put Ishmael here. How cool, we found a burial site, a specific graveyard, called Nahom, the only one for hundreds of miles around, and gee golly, the BOM says Ishmael was buried in Nahom. How cool is that? Correlation after correlation after correlation. Even if Joseph Smith had seen the name Nehem on a map somewhere, I mean, there is no way he could have known it also happened to be a special sacred burial site, the only one in southwest Arabia!

Except, A&D$FG!!, Nehem is not a burial site. And therefore this “correlation” makes no sense whatsoever. If Ishmael was buried in the Nehem area of Yemen, it could have been anywhere. Under a pile of rocks on a random spot on one of the hundreds of mountains. Plus, the burial sites referenced, there are sites just like them all over the whole country. There is absolutely nothing “unique” about the Marib or Nehem regions in terms of burying people. This is completely false. You can’t make the claim that this is a special “natural location” when an equivalently “natural location” exists literally everywhere!

Stephan quotes Andrew: “The fact still is that the NHM on that stone doesn’t match with the Nehem characters in arabic.”

NHM in any South Arabic inscription will not match any characters in Arabic because it’s an entirely different alphabet. Are you trying to say that that Arabic pronunciation of the Nihm tribe could not be pronounced as NHM with some added vowels? I think that’s going to be a losing argument. Nehem is a transliteration that is literally on maps and a plausible way of rendering at least one Arabic dialect’s pronunciation of Nihm.

What exactly is your point about modern businesses in Saudi Arabia or Qatar bearing the Al-Naham name? Whether or not the names come via the proprietor’s descent from the ancient Nihm tribe, the fact is that NHM place names in both modern and ancient Arabia are rare. It’s quite cool that the location of an ancient tribe bearing that name is nicely located in a way remarkably consistent with the Book of Mormon, being generally south-southeast of Wadi Tayyib al Ism, where we have a beautiful candidate for the long-mocked River Laman, and nearly due west of another long-mocked implausible place, Bountiful, just as the text indicates.

As for borders and mountains, have you read the works of Aston or Potter on the issue of the possible routes and the significance of “borders”? Have you read the recent paper on the route to Shazer? See https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/nephis-shazer-the-fourth-arabian-pillar-of-the-book-of-mormon/. There you will see that Nephi was very close to the Red Sea at the River Laman, and then as they moved south-southeast toward Shazer, got further way, but then they were close again as the came to the region near Sharma and the candidate for Shazer. As they continued in roughly the same direction, they were at least for a while quite close to the Red Sea. Whether they continued along the shore at that time or soon moved to the other side of the mountains paralleling the Red Sea is a topic of debate right now, but both can count as being near the Red Sea, at least for a while, and certainly near the “borders” of the Red Sea (note that the word “borders” in Arabic can mean “mountains” as well). The issue is which side of the mountains and for how long. While that is a topic for debate, the general direction given can bring one down to Wadi Jawf (with some details left out, obviously). Perhaps they stayed along the coast until nearly into Yemen, or, or example, perhaps they crossed near modern Mecca along what is today Highway 15, which is still often closer to 50 miles, not 150 miles, from Red Sea. We don’t have the details of how or when they moved more eastward away from the coast, but they certainly started near the Red Sea. Even after crossing into the elevated region, seeing that the mountain range follows the Red Sea, staying near that range even when on the east side could count as being near the Red Sea or especially near the borders of the Red Sea. What’s important is that coming generally south-southeast from the River Laman, they could readily arrive at an excellent candidate for Shazer, and then continuing, they could reach Nahom. And turning nearly due east from that point, could reach either Wadi Sayq and Khor Kharfot, or Wadi Darbat and Khor Rori, both viable candidates for Bountiful. Will you tell us that favorably discussing the proposed candidates for Bountiful also somehow mocks the Church?

Early reports of a late date for the altars were wrong, and scholars generally recognize that they are from the 7th to 8th century BC.

The general area of Nihm tribal lands are elevated, but include lower wadis as well as mountains. They are not inaccessible from other populated areas. It’s a climb coming from sea level, but there are ways to get there without scaling cliffs. Again, Highway 15 shows some potential routes.

Yes, the altars were near Marib, about 70 miles east of the proposed region for Nahom, not right in Nihm lands, but clearly FROM a member of the nearby Nihm tribe. That shows that the NHM tribe was in the region in Lehi’s day — not Marib specifically, but in a region that would be influenced by Marib. Non-LDS scholars recognize that the NHM word refers to a Nihmite from the land of Nihm west of Marib, who made a big donation to the temple of three votive altars. It’s the ancient NHM tribal lands that are in the right place, but if NHM lands went as far as Marib in that day, it’s still in the right place because Bountiful was reached by going east of Nahom, passing not far from Marib (or some have proposed through or very near Marib). If the video didn’t give the most accurate nuance on this matter, that’s too bad, but it’s a minor slip.

“BOM says they were at the coast, not 140 miles inland.” It does not say that they were still on the coast when they came to Nahom. That’s your view, but one we need not accept.

“Nehem” as a burial site gained some interest in the early days of excitement about Nahom because a map by the Yemen government shows “Nehem” as an “ancient burial site”, situated roughly within modern Nihm tribal lands. That was published in Aston’s In the Footsteps of Lehi. There are burial sites in many regions, so that alone is not a big deal, granted. But having the Nehem name pegged to an ancient burial site was interesting, that’s all. Best not to make too much of that, though.

Jeff says: “Best not to make too much of that, though.”

That about sums up the topic.

Andrew already responded “a whole bunch of liberties are being taken to correlate data for which no relationship has actually been established.”

Andrew’s apparent conflating of South Arabic script with Arabic seems to be the only concrete thing we have from him, but this may be due to gaps in the second-hand transmission of his thoughts. But asserting that he claims “liberties are being taken” with unspecified data is not a meaningful response — it’s just a verbose way of saying, “No, you’re wrong” without explaining what is wrong and why.

Correction: not a verbose, but succinct way of saying your are wrong.

What you did, Jeff, was verbose. In your verbosity, I missed where you address Andrew’s claim that the altar is not even in the Nehem region. Can you address it more succinctly?

Sorry you missed the reply in my comments of Aug. 7, 2022:

“have you read the works ”

Yes and it was excruciating to watch them torture the data to death trying to make it to talk.

If you are going to criticize those works, I would expect some kind of meaningful explanation about why, something that at least indicates familiarity with the data that you allege was tortured and a rational explanation of which arguments abuse what data.

So let me try to help you focus on the specific claims you are making. I believe you are saying that Nephi’s mention of being by the borders near the Red Sea is an obvious problem for Nahom. If you can at least theoretically consider the proposed path from the River Laman to Shazer proposed by Aston, do you see any obvious problem with that potion of the journey in terms of its relationship to the Red Sea and the south-southeast direction given? Can you agree that at a rough, macroscopic level, extending that general direction could eventually put one in the vicinity of Nahom, even though there may have been a jog or two along the way?

Second, let’s consider the “borders.” After being at Shazer, Nephi reports in 1 Nephi 16:14 that “And it came to pass that we did take our bows and our arrows, and go forth into the wilderness to slay food for our families; and after we had slain food for our families we did return again to our families in the wilderness, to the place of Shazer. And we did go forth again in the wilderness, following the same direction, keeping in the most fertile parts of the wilderness, which were in the borders near the Red Sea.” He may have been traveling along the coast for much of this journey before taking a jog eastward, but if one views the mountains as a divider, boundary, or border running along the Red Sea (not irrational in that part of the world where “borders” in Arabic can mean “mountain”), then that verse could fit even if they were on the east side of the range. We don’t have all the details, but is there anything fundamentally wrong with continuing from Shazer in roughly the same general direction as Aston shows for the trek from the River Laman to Shazer?

“Nephi’s mention of being by the borders near the Red Sea is an obvious problem for Nahom”

Not really. It is a demonstration of Texassharper/Bible code type connection fabrication. The constant careful re-readings and re-interpretations from blowing dust off the text results in making it mean what ever you want it to mean. You can write volumes of verbosity to make borders not mean barrier or how the Church translates it in its arabic edition. Whatever.

“do you see any obvious problem with that potion of the journey in terms of its relationship to the Red Sea and the south-southeast direction given?”

Are you paying attention. Of course we see no problem. That is the point isn’t it? It could be anywhere is the point, even Qatar etc., as Andrew and any others have pointed out. Sigghhh ….

Stephen Smoot (essential stating the same as Jeff’s post here): “Frankly, it is hard for me to escape the conclusion that the only reason why you are claiming “it’s not known that this tribal name matches with the Nehem place name” is because you don’t want it to match. Literally every single authority on this I have encountered, both Mormon and non-Mormon, conclude that the Nihm tribe and the Nehem/Nehhm region noted in later Islamic and post-Islamic sources are one and the same.”

Andrew replies:

Well you’re really going out of your way to be disagreeable and distract from your inability to link the two, aren’t you?

The fact still is that the NHM on that stone doesn’t match with the Nehem characters in arabic. Repeating myself, I’m still failing to understand the significance of this point though, because the burial location isn’t in Nehem to begin with.

Off hand I’m thinking of some people we could consult though. A company in Saudi Arabia called Naham Tech, owned by the Al-Naham family. I wonder if they have any relatives buried in Saudi Arabia? Could take this research in all kinds of new directions. And then there is the Al-Naham restaurant in Doha. You know, come to think of it, that’s pretty interesting. Maybe we’re looking at this all wrong. Nephites didn’t follow the coast along the red sea, they followed the coast along the arabian sea, but to them it looked “red” in the fleeting light! And then they turned eastward into Qatar. Northern end of the peninsula you’ll find some hidden gems with enough wood to build at least one or a couple ships.

I read the exchange above and shake my head in disbelief. The continuing inability of anti-Mormons and cultural Mormons alike – whichever category Stephan and Andrew fall into – to articulate any kind of coherent response against the facts concerning NHM is becoming one of the strongest evidences FOR the position that Jeff Lindsay has presented so comprehensively in his blog.

Neither Stephan nor Andrew have mastered the basic, essential, texts on the subject they comment on, resulting in statements by them that are often silly and childish. When so many established FACTS – firm data about directions, language, geography, history, and common sense (all things not subject to belief or bias) – are argued against by both of these persons their intellectual dishonesty and agenda stand revealed.

Warren Aston

Warren, thanks for dropping by! The responses are puzzling, but are representative of what happens when people have an conclusion that blinds them to even discussing alternative possibilities. This is not just a result of having a strong belief one way or the other — there are many Christians, Muslims, Jews, and atheists that can look at evidence for some aspect of the Book of Mormon such as chiasmus and say, “Hey, that’s really interesting” without having to surrender their core beliefs and still retain their doubts about our faith. But when one is absorbed by a zealous, blind faith not in God but in a zealous cause such as “Mormonism must be wrong,” then genuine intellectual engagement with other views tends to become impossible. All that matters is the holy war of attacking everything in sight, never surrendering an inch. All evidence must be denied by spray painting circles around it followed by adding the graffiti of “Texas sharpshooter strikes again!” across its face.

The mysterious scholar Andrew declares that the NHM inscription on three altars (among many ancient inscriptions mentioning the NHM tribe) does not count as evidence for Nehem/Nihm because those letters don’t match the Arabic name. What on earth is he trying to say? It sounds ike his objection is that the ancient South Arabian script is not the same as modern Arabic. Of course it’s not — but why would you expect any script from 700 B.C. to be in much more modern Arabic, for which the earliest known example is from 512 AD?

Andrew then channels the most misguided response to Nahom that I’ve seen, the notion that finding related NHM names of any kind somehow neutralize the significance of the convergence of multiple issues found in the Arabian Peninsula evidence. He argues that a technology company in Saudi Arabia with the AL-Naham name or a similarly named restaurant in Qatar provide evidence against Nahom in Yemen, something that’s already been treated in one of the first issues raised in the post, citing “Noham, That’s Not History.” At this point it’s clear that the mind behind that argument is not even recognizing the most basic facts associated with Nahom. What we see is an all-out effort to deny the evidence by regurgitating any argument, and, in grand Texas sharpshooter style, declaring victory after hours of online searching when finally finding a modern restaurant bearing the Naham name in Qatar. What’s next, pointing out that another NHM name exists in California, the modern coined name “Anaheim,” and then feeling a sense of triumph for a successful brilliancy, unable to see what a Mickey Mouse argument it is?

Jeff suggests anyone who questions him must be stating “Mormonism must be wrong.” Talk about a zealous cause lacking genuine intellectual engagement.

I am curious Warren. What facts did Stephan or Andrew disagree with? As I read it, they disagree with conclusions not facts. I know you will invent something to pretend we have, because if you don’t you self convict yourself of being intellectually dishonest.

Oh and Warren … you imply accepting your Nahom theories is an 14th article of faith. Care to demonstrate your intellectual honesty and clarify that it is not and the truth is no member is require to accept your theories and any member who doesn’t accept your theories is not a lesser member?

” Can you address it more succinctly?”

I can’t seem to reply to the post I wanted to. But Jeff’s answer indicates he cannot retort succinctly, because Andrew was right. Jeff has to verbosely explain why everything is in exactly the right place because his Texas bullseye is much wider diameter.

NHM/Nahom/Nehem is the silliest argument ever for or against the Book of Mormon. This whole thread of comments and the original post is so much speculation about stuff that isn’t evidence of anything or against anything.

It is like one datapoint. And not a very good one. If there was more to the archeology record here to support the Book of Mormon claims – say carvings in reformed Egyptian that said Nephi was here or something crazy. But it does not. It is a common sounding three letter word that is present in the Bible and Book of Mormon.

There is no speculation about the meaning of NHM on the inscriptions on votive altars at a temple near Marib. It refers to tribe of the donor, the NHM tribe, today often written as Nihm, whose tribal lands have been spelled as Nehem and Nehhm on some old maps. There is also no speculation that tribal names can be used to describe lands and cities or towns associated with the tribe. Verification from archaeological evidence for the presence and prominence of the NHM tribe in the 7th or 8th century BC not far from Marib, whose tribal lands continue to exist in Wadi Jawf today, is more than just a random data point. There is a significant nexus between the ancient location of Nihm tribal lands and places today that still bear forms of the Nihm name with the miraculous candidate for the River Laman and the candidate for the place Shazer to the north and the miraculously good candidates for the place Bountiful nearly due east of Nahom/Nehem in southern Oman, precisely as the text requires. There should not be cool candidates for any of these places if the Book of Mormon were a fraud.

The basic shape of Lehi’s trail, a south-southeast leg coming down into Yemen with an eastward turn toward the coast of Oman, was already being published in a rough form by the Hiltons before the NHM inscriptions were found. This was not a case of finding some random village or tribe name anywhere in Arabia and then forcing a narrative to fit it, Texas sharpshooter style. This is a convergence of details with surprising evidence joining them together and establishing plausibility. A surprising candidate for the River Laman exists, 3 days south of the borders of the Red Sea (by camel) as the text seems to indicate. Follow Nephi’s description of going south-southeast from their encampment on the River Laman for four days and there is an excellent plausible candidate for Shazer. Continuing in that general direction can bring you to Nahom. Then turning due east at Nahom can avoid the Empty Quarter just north of that route and another great dessert to the south, and lead you straight to Wadi Sayq without impossible barriers, and then on to Khor Kharfot (or nearby Khor Rori on Wadi Darbat, George Potter’s viable candidate) as a miraculous candidate for Bountiful with the largest freshwater lagoon in the entire Peninsula, and still essentially uninhabited as Nephi seems to imply, with fruit, water, rare iron ore, cliffs over the ocean, a mountain, and other details fitting the text. It is the ideal location of NHM lands / Nehem / Nahom in or near Wadi Jawf, a little west or northwest of Marib, relative to the long-mocked-but-now-substantiated River Laman candidate and Shazer candidate and Bountiful candidates that make archaeological evidence of the existence of the rare NHM name in Lehi’s day (or slightly before) a fascinating tidbit.

Nahom is not just a random name. It represents a populated area that others called Nahom/Nehem/NHM found by Lehi at the end of a long southward trek from the River Laman and Shazer. It is place from which one can turn nearly due east and safely reach the coast, and there find a highly unexpected treasure with fruit and resources to live and even craft a ship, with some divine guidance. (Potter’s proposal for Wadi Darbat + Khor Rori gets more into the details of how the shipbuilding may have been done and why Khor Rori would be an excellent place to build and test a ship.) There is a great deal of merit top the proposal that a place within ancient NHM tribal lands was what Lehi and his family heard being called the place Nahom. It fits with the River Laman and Shazer evidence. It fits perfectly with the Bountiful evidence. The Nahom name (here perhaps hearing or using a related Hebrew word rather than the Southern Arabic NHM) even provides an appropriate Hebrew wordplay that fits the scene of mourning and murmuring described in 1 Nephi 16:34. All of this speaks to the antiquity and authenticity of Nephi’s record.

Seriously, solid candidates for Bountiful are nearly due east of Nehem/NHM lands, which are roughly south-southeast of the River Laman. These places aren’t supposed to even be possible — a green Bountiful in Arabia? A river (a continually flowing stream, to be more precise in modern lingo)? These were things that critics were mocking just a few years ago, and now we have solid candidates for these impossible places — and now there’s a Nahom candidate that’s in precisely the right place to properly connect these candidates. And you can just dismiss all this as non-evidence?

It doesn’t make the Book of Mormon true. It exists yes – not arguing that there were not people that may have used this word in their historic people and place names. It’s existence doesn’t prove the Book of Mormon is true or historically accurate.

My point is laser focusing on this point is not the evidence you think it is to prove that the story was true. I have read multiple of your posts on this as well as articles you link to and it just isn’t convincing. If this is the best evidence we have to support historicity of Nephi and Lehi’s story then it is pretty shaky.

It doesn’t make the Book of Mormon true. It exists yes – not arguing that there were not people that may have used this word in their historic people and place names. It’s existence doesn’t prove the Book of Mormon is true or historically accurate.

As you say. It is an interesting tidbit. But that is all. A tidbit.

My point is laser focusing on this point is not the evidence you think it is to prove that the story was true. I have read multiple of your posts on this as well as articles you link to and it just isn’t convincing. If this is the best evidence we have to support historicity of Nephi and Lehi’s story then it is pretty shaky.

Brian –

Jeff is honing the art of talking past others. A little surprising, as this is a hallmark of someone a third of his age. Time has not been kind to him.

His position regarding the Nahom Connection (now the greatest film of all time for cultural Mormons such as Jeff and Warren Aston) has radically evolved over the last twenty years, despite no new significant information on the subject in the same time frame. He modifies his conclusion from Nahom is a curiosity, to a plausible connection, to extremely interesting, and now to “implausible that Joseph Smith … could have concocted the details given for Lehi’s Trail.” This instability in his conclusions comes in the context of deteriorating foundations in other old school positions in the subject area of Mormonism.

As Jeff knows, you never said the fact that NHM is inscribed on an altar is speculation. Jeff just deliberately and deceitfully talked past you, falsely claiming you communicated this. The speculation that Nihm is the same Nehem and then this Nehem is Nahom and then therefore the originally Nihm was where the altar is, is obviously speculation. Jeff even verbosely agreed with Andrew that the altar is not in Nehem.

This is just one example of the speculation you are referring to. Jeff even slipped up and admitted there are more candidates for Bountiful. His preferred candidate is his speculation. Oh, and none of the candidates are ancient locations of trans-oceanic vessel building, probably because the Book of Mormons declares the whole thing to be a miracle. Jeff is semantically morphing his preferred reading of the literature/record to make the geography match something meaningful to him and then declaring anyone who finds this whole methodology distasteful as obtuse anti-Mormons.

It is enough that in this thread here, Warren Aston demonstrated his own intellectual dishonesty by his own standard. Warren Aston practically confessed to it.

Considering that Jewish tribes had already been spreading out from the Levant for centuries prior to Lehi’s departure, and the fact that NHM is Shemitic, I believe it is more than likely that Nahom was a family name of the House of Israel. In that case, a land named after a tribe would not be unusual at all since this was common practice in Judea and Samaria.

What a gem to have visit from Dan Vogel!

Is the thread linked below, cultural Mormon Warren Aston ran away defeated. Let see if he runs away again.

https://www.arisefromthedust.com/nahom-nhm-only-a-tribe-not-a-place/#comments

This is not for publication.

I appreciate your confidence in leaving criticisms on the page and for your robust rebuttals. Thanks for all the articles and links that are available on this web site. Do you have an app for mobile phone use? It would be nice if you did. Thanks again.