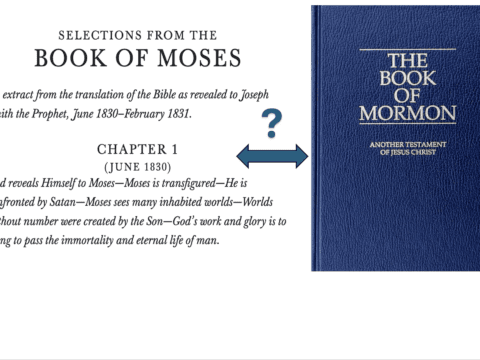

As I’ll explain in more detail in the near future, an important verse in considering possible connections between the ancient brass plates and the Book of Moses is found in Moses 7:26, which refers to a vision of Enoch:

26 And he beheld Satan; and he had a great chain in his hand, and it veiled the whole face of the earth with darkness; and he looked up and laughed, and his angels rejoiced.

Tonight as I was writing about this verse, I was curious about the imagery. How could a chain veil the earth? Chains aren’t especially opaque. Fortunately, Hebrew is. So I used my Blue Letter Bible app to search for “veil” and “chain” in the Old Testament. The first hits I found for both gave me these words:

- Candidate for “chain”: Strong’s H7242 (רָבִיד), rabiyd, a neck chain or collar according to Gesenius’s Lexicon, used in Genesis 41:42 (Pharaoh gives Joseph “a gold chain about his neck”) and Ezekiel 16:11 (“I decked thee also with ornaments, and I put … a chain on thy neck”).

- Candidate for “veil”/”vail”: Strong’s H7289 (רָדִיד), radiyd, a “veil” in Song of Songs 5:7 and “vails” in Isaiah 3:23, a word which means something spread, a wide wrapper or large veil, or, in Gesenius’s Lexicon, “a wide and thin female garment, a cloak.”

Bring me down to earth on the problems with these proposals, please, but for now, I quite like these possibilities. If these words were actually used in a Hebrew document (say, on the brass plates–more on that later), then Satan’s chain, a rabiyd, wouldn’t necessarily be something that looks frightening, but is something ornamental and attractive, the kind we might gladly receive and wear around our necks with pride, only to realize too late that, like the golden handcuffs we speak of in the business world, it limits our freedom. Satan’s pretty chains are chains of slavery. They connect us to his crushing yoke and lead us captive into bitter servitude. And we like fools are happy to clasp them around out necks. “Wow, thanks, it’s so shiny!”

Second, the veil as some form of radiyd would seem appropriate, for it would be a cloak, spread out widely over the earth. And what a nice word play with rabiyd. Four letters, three of which are identical, and the “b” and “d” sounds aren’t that distant phonetically. To me, it sounds like a winner as far as Hebraic word plays go. But I really don’t know, so I welcome your feedback. Of course, the Book of Moses has “veiled” as a verb, not a noun, but perhaps “veiled” could be translation of a construction literally meaning something like “to act as a veil.” Let me know if that is a problem.

If this could be a legitimate albeit speculative word play in Hebrew that someone has already noticed and written about, either regarding Moses 7:26 or some extant Hebrew text, I would appreciate a reference to cite. I’m working on an article where it might be helpful to cite such a reference. In any case, I think that Moses 7:26, word play or not, has some significance for the Book of Mormon that I hope to discuss more fully as part of an article I’m working on. If the word play is plausible, it would add a little more intrigue to the beauty of the LDS scriptures.

If you could make your rabiyd into the headband that would suspend a veil over the face, instead of a necklace, then you might perhaps turn this verse into an image of Satan marrying the Earth, and adorning her with a veil of darkness. I'm not sure there are really any marriage customs where the groom veils the bride, but maybe Satan's deception is firmly established as a kind of veiling, and it's enough to just associate that with a bridal veil.

Moses 7 seems to be mainly about the taking up of the holy city of Zion into heaven, while the rest of the earth falls into Satan's power. Bridal imagery here would therefore be a sort of perverse echo of Revelation 21, in which the New Jerusalem descends from heaven adorned as a bride.

If Mormons are edified by any of this hypothetical reconstruction of original Hebrew wordplay or imagery, then great. I don't think it works well as apologetic, because when one allows oneself this much freedom to speculate about hypothetical Hebrew originals, it's just not surprising that one can come up with a certain number of plausible cases. A jingle of rabiyd and radiyd may be better than a great chain that veils, but it's not a jackpot of profound meaning that makes the reconstruction compelling.

The theory that Moses 7:26 had a more coherent Hebrew original is also somewhat problematic, it seems to me. Whatever an original Hebrew might have been, bridal image or jingling wordplay, the English text is just awkward. If the Hebrew original was better, the translation failed to capture it. As I understand it, the Book of Moses is supposed to have been revealed to Joseph Smith by God, or miraculously translated by the power of God. So how well does it really fit with Mormon doctrine, to suggest that Moses 7:26 is a bad translation?

I have always thought it interesting that a study of holy writ has something for everyone. It gives satisfaction to those simply seeking for hope and peace, yet also gives those searching for deeper meaning something more to do.

I don't think Jeff was looking for – or claims to have found – some earth-shattering evidence for LDS belief or interpretation. It seems he is just trying to appreciate some of the subtleties of scripture that are not readily apparent, but that enhance the experience and understanding one might (and often does) get with more in-depth searching.

James, I suggest the following because of your interest and work in the hard sciences. This particular matter aside, no hard evidence from the BofM that you have encountered works well as an apologetic for you. Your soft judgments on these topics are rather uninteresting at this point. What would be interesting is for you to engage substantial hard evidence of your choosing, write an article for a receptive Mormon journal arguing for a naturalistic view, against the apologetic. Then the debate could be engaged academically. Cheers.

@ anonymous:

I'm sorry if my comments are uninteresting. I'm just curious about how Mormons think about things. It surprises me that intelligent people can really believe some of the things Mormons believe, but evidently some intelligent people can and do, so I'm curious about how. Several times I've gotten answers here that did help me see how an intelligent person could take the Mormon viewpoint. When this has happened, I've acknowledged it.

I don't know what substantial hard evidence for the Book of Mormon I could choose to engage, since as far as I know, there is none. "Substantial hard evidence", to me, would be something like the ruins of Zarahemla. Arguments which only purport to show that if Joseph Smith were a fraud, then he would have to have been an awfully darn good fraud, do not count for me as substantial hard evidence for the Book of Mormon.

@bearyb:

Reading again my sentence "If Mormons are edified by any of this …, then great," I admit it sounds a bit snarky. But I really didn't mean it that way. If people get something out of this, then that is great. I recently argued here that God could in principle send meaningful revelations in snowfall, or in redacted compilations of ancient myth. However the Book of Moses really came about, if you can find meaning in it, then you've found meaning.

I also really am curious, though, about how the kind of in-depth searching that Jeff has done in this post really jives with the Mormon theory of revelation. Biblical scholars often clarify strange passages by improving on poor translations from the original versions. When this happens, the original versions are usually available, at least with fairly high confidence. Occasionally there is speculation on what an unavailable original version might have been.

For example, I've heard such a speculation about Jesus's famous statement that it is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich person to enter the Kingdom of Heaven. The speculation was that there might have been either wordplay in what Jesus actually said, or confusion about translating it into Greek, because in Aramaic the word for 'camel' sounds a lot like the word for 'rope'. What Jesus actually said might therefore (says this speculation) not really have been quite as absurdly extreme as the version we have.

Even in that case, there actually is an ancient Aramaic version of the New Testament; and many Christians would accept that Jesus's spoken words could have been imperfectly preserved in the Greek texts, because minor discrepancies among the oldest manuscripts have long been known. No translation into English has ever been considered inspired, and so improving the English text with the help of original versions is perfectly in order. Given the different Mormon teaching about how the English text of the Mormon scriptures was produced, it's just honestly unclear to me how Mormons really think about the kind of point that Jeff has made in this post.

"As I understand it, the Book of Moses is supposed to have been revealed to Joseph Smith by God, or miraculously translated by the power of God. So how well does it really fit with Mormon doctrine, to suggest that Moses 7:26 is a bad translation?"

James, you may be overstating the extent to which Mormons believe that the Book of Moses is a revealed translation, or you may be conflating the Book of Mormon translation with the Book of Moses translation.

Mormons believe that the Book of Mormon translation was revealed, and I think it's safe to say that most Mormons would accept Joseph Smith's statement that the Book of Mormon is the "most correct book on earth." But even then, we don't believe in inerrency. The Book of Mormon itself claims that it is not perfect. I suppose you could draw a distinction between the text and the translation and argue that even if the text itself is not perfect, the translation was perfect, as it was inspired/revealed, but I think even the most conservative Mormon would accept the possibility of translation errors in the Book of Mormon.

The case for inerrency in the Book of Moses is even weaker. It was not a separate revelation, but was a part of Joseph Smith's biblical revision, which he referred to as a "translation." Joseph Smith did not, to my knowledge, ever make any claim that his biblical revision was "the most correct," such as he did with the Book of Mormon. And the majority of the biblical revision (called the Joseph Smith Translation, or JST by the LDS church) is not even accepted as canonized scripture by the church. It is treated as a helpful study aid, but not a replacement for the KJV. The Book of Moses has been canonized, but the fact that it was canonized and the rest of the translation was not is really more the result of historical accident than a conscious decision that the Book of Moses is somehow more reliable than the rest of the JST.

So in short, Mormons don't claim the sort of inerrency for the Book of Moses that your comments seem to assume. The closest Mormons come to inerrency is the belief that the Book of Mormon translation was inspired by God, but even then, we don't claim that that makes it without error.

I'm also not sure that Jeff is arguing that these verses are a "bad translation" as much as they are a more literal translation. Every translator has to choose between on the one hand sticking closer to the source language, which will yield a more literal translation, but will obscure poetry, rhyme, meter, etc., and some of the idiomatic meanings that are apparent in the source langauge, and on the other hand trying to translating some of the elements of rhyme, meter, idioms, etc. into the target language, which will require a much looser, less literal translation. I think the point that Jeff is making here is not that these verses are a bad translation, but that they are a much more literal translation, which obscures the hypothetical Hebrew wordplay unless you know how to back into it by hypothesizing what the Hebrew source words are.

To answer your question about how Mormons think about that kind of point, personally, as somebody who is an active, believing member of the LDS church, I regard the kind of point like that made in the OP as sort of mildly interesting, but far to speculative to really prove anything. I certainly wouldn't base my decision to accept the claims of the church on it. But if somebody finds meaning in it, I won't begrudge them that. I actually thought your comment that it was not a very convincing apologetic, but potentially useful as devotional material was pretty well-stated. But then I don't find much use for apologetics, personally, so I may be a biased source.

So in short, Mormons don't claim the sort of inerrency for the Book of Moses that your comments seem to assume.

A lot of Mormons would disagree with you about that. Can you give us an example of an error in the Book of Moses?

Ah: thanks very much for the clarification. I had indeed been assuming that the Book of Moses was considered to be revealed like the Book of Mormon, perhaps even under 'tight control'. If this isn't actually part of Mormon belief, then Jeff's kind of hypothetical expansion of the canonized text is clearly not such a problem.

And, once we are not talking about divine translation, then 'bad translation' might indeed just mean ordinary human translation, which makes compromises. Conceivably the original was just awfully tricky to put into English, and Smith went for a literal rendering. Suggestions about a hypothetical original text for the Book of Moses are still more speculative than analogous suggestions about original Bible texts, but Jeff's just making a suggestion.

And from the general tone of his post, I think it probably is directed more towards Mormons than to non-Mormons. Jeff likes to use putative Hebraisms in the English texts of Mormon scripture as apologetic evidence, but in this case he seems to be offering the same kind of thinking just as food for Mormon thought — kind of like a restaurant owner serving their own family the same food that's on the menu for guests. To use the crude business buzzword, Jeff is "dogfooding".

I think this is an important part of what a good apologist should be doing, even though it isn't apologetics per se, because it would be bad if apologetic arguments became entirely separate from the thinking of already committed believers. Suppose some religious apologist comes up with an absolute humdinger of an apologetic argument, which somehow reels in converts like crazy, but which is just utterly foreign to the whole mental and spiritual culture of the religion as it is actually practiced. That argument would really be at best a bait-and-switch, which is a pretty dishonest tree to be growing the fruit of true faith. To make sure this doesn't happen, it probably helps to keep doing things like this post of Jeff's, to maintain contact between the apologetic front lines and the home front.

Suppose some religious apologist comes up with an absolute humdinger of an apologetic argument, which somehow reels in converts like crazy, but which is just utterly foreign to the whole mental and spiritual culture of the religion as it is actually practiced.

Happens all the time. My wife was drummed out of her relief society teaching calling for saying that not everything that comes out of the church authorities' mouths is revelation, but that's a favorite apologetic argument.

I'm just curious about how Mormons think about things. It surprises me that intelligent people can really believe some of the things Mormons believe, but evidently some intelligent people can and do, so I'm curious about how.

Let's start with the Book of Mormon. Joseph Smith referred to it as "the keystone of our religion." That means that without it, the LDS Church would not exist. It is the most tangible evidence we have of Joseph's prophetic calling.

So how could an "intelligent" person ever believe in such a thing? The answer lies not in "hard evidence," but in experimenting on the word. How or why does anyone believe in the Bible? Same way, hopefully. The correct process is explained in great detail in Alma 32, with other examples found througout the book, and with a clear challenge to engage in the process in Moroni 10.

A "testimony" based on any other thing besides the result of such an experiment is shaky at best. Unless and until a person has tried it they have no grounds upon which to base any criticism of such belief as can result – similar to so many other things in life that, until experienced, may not be understood.

So, if anyone wants to destroy the Church, they will first have to destroy the Book of Mormon.

Though not the basis of my belief in the BoM, it seems to me that evidences supporting it grow stronger, while arguments against it are sorely lacking.

What surprises me is that so many intelligent people do not recognize or acknowledge the inner longing of their soul to know of such things, or indeed, that they can be known. It seems much easier to distract ourselves with other, more apparently pressing temporal considerations while ignoring the weightier matters of eternal things. After all, the spiritual consequences of decisions do not seem immediate or tangible, especially for those not accustomed to recognizing them.

As an example at the other extreme, consider Christ's response when the woman touched the hem of His robe in the crowd. What did He say, and what could He have possibly meant by it?

Bearyb,

This test you use to determine the truthfulness of the BoM, it can be applied to any religious text or even any self-help book. It is not a test that can be relied upon to determine which church to join. I can read Mere Christianity and put into practice C. S. Lewis's beliefs about the Christian life. If I receive fruit from this, does that therefore mean that the Trinitarian doctrine, which Lewis expounds upon so eloquently in Mere Christianity, is true? Or if I read the Koran, and put into practice those admonitions, and receive blessings in my life, does that mean I should convert to Islam?

And what do you do after you read the Book of Mormon and gain a testimony that God is unchangeable from all eternity and to all eternity (Moroni 8:18), and join the church, but then find out that, as Smith preached in 1844, "we have imagined and supposed that God was God from all eternity," but that Smith refuted this idea and preached that God was not unchangeable, but he was once a man. What do you do then?

Perhaps the past eternity — æternitas a parte ante — is anchored to terrestrial or human time. Who knows.

It may be that many people ignore their souls' longings. But I wouldn't say that everyone who is not convinced by the Book of Mormon must be doing that. Billions of human beings are religious. Less than 1% of these are Mormon.

Anonymous,

So you are saying that "eternity" does not mean eternal?

Everything Before Us:

Sorry to jump in between you and Bearyb, but to me, if there is a conflict between canonized scripture and uncanonized preaching, it seems to me almost a no-brainer that scripture trumps preaching. But maybe that's a cop-out. It's clear that many Mormons give precedence to the later sermons of Joseph Smith over passages like the one you cite from Mormon, and there are all kinds of ways to reconcile that if that's what you want to do. Anonymous hints at one of them.

For me, personally, I think we have to recognize that on the more speculative things such as the nature of God, even canonized scripture does not speak with one voice. The only things on which scripture is arguably pretty well united are the message of the gospel, that Christ came to do the will of the Father, and will draw all men to him on conditions of repentance, and will give the Holy Ghost to those that come to him and are baptized. Those are the things that I'm certain of, and quite honestly, that's more than enough to keep me occupied. On everything else–including things like whether in some far distant time–so long ago so as to be characterized as before "eternity"–God was changing or unchanging, I can live with uncertainty.

Toni, which version? 🙂 It was revised multiple times, and lots of mistakes were corrected, which it could not have been if it was inerrent ab initio. Seriously, here's a good, but very general overview of the textual history of the Book of Moses. https://www.lds.org/ensign/1986/01/how-we-got-the-book-of-moses?lang=eng

Maybe you're saying that it wasn't inerrent in the first draft, but it became inerrent by the time it got to the last draft? That seems like an odd argument to make. Maybe there are some Mormons who claim that the Book of Moses in inerrent. I've never met one.

You must not know many Mormons. I would bet that if you polled a general population of card carrying Mormons and asked them if there are errors in the Book of Moses, the majority would consider you a blasphemer, and a large percentage (I would say close to 90%) would say there are no errors.

I took 4 years of seminary and 4 years of religion classes at two different church schools, and though we discussed the contents of Moses in great detail, I was never taught that it was a lesser scripture, nor were any errors ever discussed.

It sounds like you are taking the church's new stance about The Pearl of Great Price (specifically the Book of Abraham) that it doesn't matter how it came to be, it's the doctrine it conveys that's most important.

None of what you said establishes that inerrancy is a doctrine of the church.

None of what you said establishes that inerrancy is a doctrine of the church.

Well, ebu, "eternity" can mean the whole duration of the world — in other words, it can be limited. The semantics is very hard to be sure of. The matter appears to be inconclusive.

"from all eternity to all eternity" seems to be quite direct and clear. It at least tell us what Joseph Smith thought of the nature of God in 1829. The fact that he then uses the same language to refute the idea of an eternal God is quite telling.

I hope you realize that the matter only appears to be inconclusive to you, who so desperately needs Joseph Smith's later additions to Christian theology to seamlessly attach themselves to Christian theology. No other Christian has this same problem. Because Christians have always consistently believed in the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, the ETERNAL God.

Moroni 10 contains the famous challenge to pray for personal divine assurance that the Book of Mormon is true. The whole idea has bothered me since I heard about it, and I think maybe now I can articulate why.

You have to make your prayer "with real intent". To me this means that you're prepared, in principle, to be convinced — otherwise, I would say, you're just pretending to pray for guidance, but not really asking. But if you're praying for the truth of the Book of Mormon to be manifested to you, being seriously prepared to conclude that it is so manifested, then it seems to me that you must already have decided that all that stands between you, and firm commitment to Mormonism, is experiencing a certain feeling. To me, even before you either get or don't get that feeling, deciding to let a feeling make that big decision for you means you're already in a pretty peculiar state of mind.

Suppose a person decides to marry the next green-eyed stranger they meet. I won't be surprised if this person then immediately falls head-over-heels in love with that next green-eyed stranger, because the only reason anyone decides to marry the next green-eyed stranger is that they are desperate to marry someone, as soon as possible; and people in that state of mind are prone to falling in love on the first excuse.

It seems to me that if you are seriously prepared to commit your life to a cause, if you only get a certain feeling, then you must really be longing to throw yourself at a cause. Given that, it seems to me that Moroni's promise is a self-fuliflling prophecy.

Nice observations James Anglin in your initial comment. I suspect you are correct in your original assumption that most Mormons would see the Book of Moses as revealed in much the same way The Book of Mormon is. I do, for one.

Your take on Moroni 10 is interesting, and I can understand why that would be disconcerting. I didn't experience it that way so I view it differently, to me "real intent" simply means with an honest heart, with real integrity in confronting one's assumptions and limitations.

I could definitely see the case you lay out occurring for some people, but I would imagine such a shaky foundation built more on desperation than an honest heart would eventually crumble. Like your hypothetical desperate love-seeker, the relationship would likely be shallow and full of dependencies rather than strength, which would crumble if the person did not mature in their love and approach to love.

The Book of Mormon does not tell us to ask God if it IS true. It tells us to ask God if it is NOT true. It expects skepticism from the start.

EBU,

First of all, it is not just a "test I use to determine the truthfulness of the BoM," it is the method contained in the book itself. I didn't invent it, nor can I judge how well anyone follows it. It is what it is.

Secondly, neither the LDS Church nor the BoM claim to have a corner on all truth. In fact, the D&C says quite clearly that if we receive a blessing, it is by obedience to the law upon which it is predicated. Obviously this does not only pertain to members of the Church. You don't have to be a Mormon to reap the benefits of obeying the Lord's law of health (the Word of Wisdom), or the benefits of obeying the Ten Commandments, or even those of the Golden Rule. There are many people of faith – and many people who aren't religious at all – who benefit by being generous with their material things.

You don't even have to be a Mormon to feel spiritual promptings! I don't think Joseph Smith was a member of any church when he received his First Vision…

As far as God being unchangeable from all eternity to all eternity, yes it says that. But it cannot mean unchangeable in every way. If you'll recall, just over 2000 years ago God the Son underwent a very drastic change. He was born on the earth into a body, within which He grew "from grace to grace." then He died, was resurrected, and continues to live as a resurrected, glorified being. What a change! So "unchangeable" must mean something else.

James,

As I said previously to EBU, I don't believe the LDS Church claims to have exclusive access to all things spiritual, or even all truth. In fact, we are taught in the Church to seek out truth wherever we may find it. We are encouraged to learn about all sorts of things and gain a wide knowledge and understanding.

Of course you do not have to be LDS to be religious. I hope I didn't mislead anyone.

Bearby,

Back in 1885, God the Son underwent another drastic change, too. He became Jehovah. Joseph Smith and others believed and taught that Jehovah was God the Father. Only until the very late 1880's did Mormons start speaking about Jesus as Jehovah. There was so much confusion, and the Q12 got so exhausted receiving letters asking for clarification, that in the early 1900's, they asked James Talmage, who had been developing the Jesus/Jehovah doctrine, to write up a statement. This is now known as the Exposition of 1916. John Taylor even wrote a hymn. Jehovah is the Father. Jesus is Jehovah's son.

As in the heavens they all agree

The record's given there by three,

Jehovah, God the Father's one,

Another His Eternal Son,

The Spirit does with them agree,

The witnesses in heaven are three.

"We believe in God the Father, who is the Great Jehovah and head of all things, and that Christ is the Son of God, co-eternal with the Father." 1841, The Times and Seasons.

"O Thou, who seest and knowest the hearts of all men-Thou eternal, omnipotent, omniscient, and omnipresent Jehovah – God – Thou Elohim, that sittest, as saith the Psalmist, 'enthroned in heaven,' look down upon Thy servant Joseph at this time; and let faith on the name of Thy Son Jesus Christ, to a greater degree than Thy servant ever yet has enjoyed, be conferred upon him." – A prayer penned by Joseph Smith in 1842.

The Kirtland Temple dedicatory prayer in the D&C also is clear evidence that Jehovah is the Father.

EBU,

Setting aside what may or may not have been understood about who was which or what was who, don't you agree that the taking upon Himself a physical body was a major change?

Why do you attempt to distract from the point I made, something that had been prophesied from ancient times and very well documented during His ministry?

Do you agree that this was a change, or not?

Bearby,

Right. I would agree that God is not unchangeable in every way if we are going to say that the Incarnation proves the changeability of God. But the claim isn't that God can't change. It is that God, perhaps while changing in certain ways from time to time to fulfill his purposes, has always been God.

If God was still God even while he was a man learning to become a God, then you are a God right now, even while you are learning to become a God. Of course, you wouldn't make this claim for yourself. Therefore, you cannot make this claim for God. When he was a man, he was not a God. Thus, he has not always been God. And that kind of God simply isn't the God described in the Bible.

If you don't believe the Bible, that is your right, but perhaps it is time for the Mormon missionaries to stop carrying the Bible around with them. It is kind of deceptive to whip out the Bible on the doorstep of an 85-year old Catholic woman and say, "We have the Bible, too!"

Yes…you have the Bible in your possession. And you read it. But you reject some of the essential doctrine found within it.

JKC,

Since inerrancy isn't a doctrine of the church, would you be so kind as to tell me which doctrines taught in the past or present are wrong?

Mormons might not believe in inerrancy, but I think most would believe that everything they have been taught is correct.

Hi EBU,

Care to define doctrine before we go down this path? For example, it was taught that the majority of the American Indians were descended from Lehi's group that came to America. As a teenager, I realized through reading various books that this just did not make sense. Some regarded this as doctrine, others did not.

What do you consider doctrine?

Steve

EBU,

"Of course, you wouldn't make this claim for yourself. Therefore, you cannot make this claim for God."

Interestingly enough, it seems Jesus approved of and reiterated this very claim. Referencing Psalm 82:6, Jesus says in John 10:

"34 Jesus answered them, Is it not written in your law, I said, Ye are gods?

35 If he called them gods, unto whom the word of God came, and the scripture cannot be broken;

36 Say ye of him, whom the Father hath sanctified, and sent into the world, Thou blasphemest; because I said, I am the Son of God?"

Joseph Smith seemed to be getting at this very reconciliation as well in the King Follett Discourse (normally I wouldn't copy and paste such a large block, but I believe it really gets to the heart of this conversation):

"The soul the mind of man, where did it come from? All men say God created it in the beginning. The very idea lessens man in my estimation; I do not believe the doctrine, I know better. Hear it all ye ends of the world, for God has told me so. I will make a man appear a fool before I get through, if you don't believe it. I am going to tell of things more noble–we say that God himself is a self existing God; who told you so? it is correct enough, but how did it get into your heads? Who told you that man did not exist in like manner upon the same principles? …The mind of man is as immortal as God himself. I know that my testimony is true, hence when I talk to these mourners; what have they lost, they are only separated from their bodies for a short season; their spirits existed co-equal with God, and they now exist in a place where they converse together, the same as we do on the earth."

Everything Before Us, It may not have been clear, but my comment was actually a response to Anonymous' comment above that I "must not know many Mormons" (which is completely false) and that in 4 years of seminary and 4 years of religious ed and church colleges he or she was never taught that the Book of Moses was "lesser scripture," so therefore Mormons must believe that is the inerrent word of God.

My point is not that Moses is "lesser scripture" my point is that any scripture, whether you categorize it as "lesser" or "greater" is not inerrent. I'm frankly surprised that some people are finding that a controversial statement. It's stupid to make this a dick measuring contest about church credentials, but I also attended 4 years of seminary, took more than 4 years worth of religion classes at BYU, served a mission, have been active in the church my entire life, and have never heard it taught as a doctrine of the church that scripture is inerrent. In fact, I was taught more than once in BYU religion classes that, if for no other reason, the very nature of human language itself means that inerrency cannot be a fact of latter-day scripture. At least one BYU religion teacher taught that "as far as it is translated correctly" is implied to apply to the Book of Mormon as well, and honestly, if you know even a little bit about the textual history of the Book of Mormon, you realize, it has to apply, if you are going to accept it as scripture. Anonymous' guess that if there were a survey, 90% of respondents would call such a view blasphemous is meaningless speculation, and not very persuasive to me since it is so at odds with

But to answer your question, I don't see how whether doctrines taught by the church are related to the question of scriptural inerrency, because inerrency has to do with scripture, not with church teaching. I think it is pretty uncontroversial that church teaching is subject to normal human error. I'm not interested in giving an exhaustive list, but there are plenty of examples: You've already pointed out the changing views on the Godhead, to which you could also add the lectures on faith version. Other examples include Adam-God, blood atonement, certainly all the justifications for the race-based priesthood ban, if not the ban itself.

I find that discussions about what constitutes doctrine vs. just teachings are rarely productive, and often just leads to a sort of circular reasoning where we say doctrine is only things that can't change, so therefore if it changed, it wasn't doctrine, even if it was presented as such at the time. And I honestly don't see what the point is of drawing the distinction between doctrine and teachings. Are they treated any differently? As far as I can tell, the only reason for such reasoning is to be able to preserve the claim that "doctrine" doesn't change. But why do we even need that claim?Whether you call it doctrine or teachings, it is clear that things taught by the church have changed and sometimes dramatically. Sometimes those changes may be able to be reconciled, but sometimes it's better to just admit that the teachings or doctrine was wrong. That's not a problem unless you have the unrealistic and unscriptural expectation that prophets are never wrong.

Having said that I will say that there is a smaller subset of "doctrine" that Jesus in the Book of Mormon calls "my doctrine," which is limited to the message of the gospel: that Jesus came to do the will of the Father, that he died on the cross and was resurrected, that all of us will be resurrected and judged, and that if we will come to Christ through repentance, faith, and baptism, he will forgive us and cleanse us by the power of the Holy Ghost. If we are talking about those things, I would agree that doctrine does not change. If we are talking about anything else, all bets are off.

Steven, that is a misinterpretation of what Jesus is saying. What you are doing is called "proof-texting."

Jesus is saying, "The scriptures call those who have the word of God (the Jews) 'gods.' So why are you making a big deal when the one who God himself has sanctified and sent into the world is called the 'Son of God.'"

He is not saying that everybody is a God, especially not in light of the fact that the only ones who had the word of God at the time he was speaking were the Jews. Nor is he saying that those who have the word of God are going to become God, and will be worshipped as such by their posterity. He doesn't say this. It is a stretch to make this passage say that. The scripture he is quoting from Psalms has to do with apostasy: "Ye are gods, but you will fall like men." When he quotes it in the New Testament he is not answering questions about the eternal progression of the human race toward Godhood. He is defending the claim that he has been sanctified by the Father and sent into the world as the Son of God.

He isn't expounding on the King Follet Discourse.

EBU,

I'm not clear what you think my interpretation is. Limiting it to the Jews doesn't change my point, as I understand it Jesus was pointing out the irony that they are condemning him for supposed blasphemy for calling himself the Son of God, while the scriptures already go so far as to call them gods. Whether the Jews only or not, Jesus seems to approve of the idea that mortal men or at least a particular subset of mortal men are gods, and therefore how could it be blasphemy or extreme to call himself a Son of God. Do you disagree?

Perhaps because I've never been Mormon, I'm getting a bit confused. Is the dispute about what exactly Mormons believe? Or about how it differs from what the older Christian churches teach? Or about whether the Mormon scriptures (including the Bible) are consistent with each other about the nature of God?

The Trinity is of course a famously mysterious concept. Its most thorough exposition, in the Athanasian Creed, is mostly negative; it is easier to say what the Trinity is not, than to say what it is. The Trinity is not three Gods. It would be wrong (according to traditional trinitarian teaching) to deny that Mary was the mother of God. On the other hand, the Trinity is not one Person (whatever 'person' means in this context). It would be wrong to say that God the Father was crucified. The Mormon theory of God definitely seems simpler than this.

Mormon teaching makes human beings bigger than traditional Christian teaching does — eternal spirits who can progress to Deity instead of created things who can be eternally saved. In contrast, though, the Mormon theory of God seems to me to make God not only simpler than the God of trinitarianism, but also smaller than the God of any true monotheism. The God of Jews, Christians and Muslims is the ultimate being who creates and controls all reality. Their God didn't just organize pre-existing stuff into worlds, but created all the material from nothing, along with space and time themselves. To trinitarian Christians, the first verses of the Gospel of John are saying that Jesus is actually something like meaning or pattern.

This is admittedly a rather extravagant theology for a bunch of jumped-up monkeys like humans. We can't even make a fusion reactor; what do we know about ultimate reality? The more limited Mormon God would still be far enough above us, in understanding as well as power, that we might be wise to obey him. Nonetheless I think I would feel awkward, as a Mormon, having to argue against traditional Christians: "Actually, God isn't nearly as great as you think."

I don't think Jesus is necessarily approving of the idea that men are gods by quoting the psalm. I think he is just using it to mess with the pharisees, pointing out the inconsistency between their slavish devotion to the letter of the law (" If . . . the scripture cannot be broken") and their quickness to condemn him for making a claim to be the Son of God, when those very scriptures go so far as to call "gods" those who received the word of God. He's saying "hey, your own scriptures call men gods, and if you claim to be so devoted to them, why is it so blasphemous that I say I'm the Son of God." By saying "it is written in YOUR law," rather than, it is written in the law, I think he is not taking a position one way or the other on whether and under what circumstances the psalm's designation of men as Gods is correct, he is just pointing out the hypocrisy of his critics.

King Follet may be true or it may not be (it isn't canonized scripture, so nobody in the church is bound to accept it) but I don't think this scripture is a very strong support for it.

James, I think we need to be a bit more precise about what really is the canonical Mormon doctrine of the Godhead and what is the appcryphal, non-canonical teaching that has grown up around it.

The canonical Mormon Godhead doctrine is very simple, you might even say vague: "We believe in God, the Eternal Father, in his Son, Jesus Christ, and in the Holy Ghost." Add to that the Book of Mormon's teaching that Jesus is "God himself," and that he and the Father and the Holy Ghost are "one God." You end up with something not all that different from the Apostles Creed. The biggest departure is probably the Doctrine and Covenants' teaching that "the Father has a body of flesh and bone as tangible as a man's, the Son also, but the Holy Ghost has not a body of flesh and bone, but is a personage of spirit."

All the stuff about the Father having once been a man is a huge departure from traditional Christianity, but it is not canonical. It is apocryphal. Some would even argue that it is unscriptural because the Book of Mormon says that Jesus was and is God "from all eternity to all eternity." Joseph Smith was unconstrained in his thinking, he was wonderfully speculative. But those teachings were never accepted as canonized scripture and they are not binding on the church.

Although, I would also suggest that the idea of the Father having once been a man is not, by itself, as incompatible with traditional Christianity as it might seem at first glance, if only because it is pretty uncontroversial in traditional Christianity that Jesus was once a man (that's the whole point of the incarnation) but that he was still God both before and after the incarnation. So the idea of God having a body is not, by itself, an insurmountable problem. In fact, portions of the Book of Mormon can be read to suggest that the Father was incarnated in some sense in the person of Jesus Christ as well as the Son (though that is not how most members read that passage, and not hoe church leaders have interpreted it).

JKC,

I agree. But Steven used this scripture "Ye are gods" to support the ideas of the King Follet Discourse. Hence the discussion.

JKC,

But while the KFD isn't canonized in scripture, the endowment has as its foundation the doctrines of the KFD. So…I think you have to agree with the KFD if you put any stock in the promises of the endowment.

JKC

You call the idea of God being once a man apocryphal, but this apocryphal doctrine is making its way through the Correlation Committee and being printed in official church manuals. This is the Mormon problem. They have a very loose definition of the word "doctrine." Something will be taught as doctrine until it is no longer taught as doctrine. And all the additional doctrines that sprung off that now-disavowed doctrine don't necessarily go away when the parent doctrine is disavowed. That is how the concept of eternal marriage survived when the doctrine of Celestial marriage had to be altered when polygamy was ended.

JKC, it may be correct that Jesus was merely pointing out the hypocrisy of those with whom he was speaking. I don't think it proves the truth of the King Follett teachings (actually it would be using "gods" in a different way than JS defines God there), only that it is an example in scripture where we see men being called gods, which I point out to say that perhaps it is not without precedent to define a god in such a way, which is a possible option to reconcile the earlier revelations in the Book of Mormon with the later Nauvoo teachings.

But whether both are teaching two truths that can ultimately be reconciled, or whether one teaches about God like Newtonian physics teaches us about gravity and the latter like General Relativity speaks to gravity in a more advanced way, or whether there was simply a error in earlier understanding, to EBU's original point – it doesn't shatter my testimony of the Book of Mormon or of spiritual truths I have learned. Testimony or spiritual knowledge is a line upon line deal, and a confirmation of one truth does not give me all light and knowledge upon all principles, and I therefore expect a constant revision of my understanding and beliefs as God reveals to me principle upon principle.

I'm not interested in proving any particular point, or debating with anyone. Just sharing my experiences and my personal understanding.

As I see it, I really love the Book of Mormon doctrine that in the last days there are but two churches only, the church of Christ and the church of the devil. I see a great purpose in the many religions and teachings that exist throughout the world, and so much good can be found in so many places. These who bear good fruit are to me who the Book of Mormon considers the church of Christ. The purpose as I see it for the restoration of Priesthood authority through heavenly messengers and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, is to be the beacon and ensign that all truth might ultimately be gathered in one in Christ, and to be the vehicle and organization by which the Kingdom of God can and will be established on earth bringing forth Zion in preparation for the millennial reign of Christ and peace on earth. It's a grand work, and the good in the Buddhism, in the Koran, in Mere Christianity, etc. are all part of it as I see it. If people pray and find truths in them that aid help them to grow and find happiness and therefore perpetuate love and the cause of goodness, then I rejoice, and to me they are my brothers and sisters.

Everything Before Us,

Right, I was responding to Steven's comments.

I'm not convinced that the atonement has its foundations in the KFD. I think it's foundations are in the Kirtland pentecost. It was used as support for KFD ideas, but I disagree with the assertion that that is the only way to interpret it. But I don't think I'll say any more about that.

Re: the loose definition of doctrine, I agree. That's something that we should be more precise about. As I mentioned above, I wish we were more willing to limit ourselves, when speaking of doctrine, to what JEsus calls "my doctrine" in the Book of Mormon, and be more okay with uncertainty as to other issues. But for a long time, we've been taken the position rhetorically that the gospel answers any and all questions, so we've gotten into a habit of inventing doctrines by extrapolation to answer questions. That's not a bad thing if you have the humility to understand when you are speculating, and to be open to further light and knowledge, but if you assume that just because the church teaches it, it must therefore be eternal truth no matter what, you're gonna have a bad time.

…and if it wasn't clear, whether apocryphal or not, I for one do believe the teachings found in the KFD. Like Joseph Smith, the ideas and truths put forth there do taste good to me. I feel it helps me understand better who I am, and to me that God's perfections and attributes came by way of work and learning and growth through opposition does not lessen what He is in anyway, for me it becomes much more meaningful and inspiring altogether.

I hope this isn't offensive, but I have read some online accounts that claim to describe some Mormon temple ceremonies. I won't quote anything from them, but my impression from them was that (if they were accurate) they did make Mormon theology seem more starkly different from my own than the Book of Mormon did. (Well, except for Jesus's massacres in 3rd Nephi — those were pretty starkly different already.)

Having sacred secrets is one thing, but to me it would be another thing if Mormons had discrepancies between what they present to outsiders as their doctrine, and what they actually practice. I myself am not saying this is so — I'm certainly not very familiar with Mormon temple practices, and those things I have read may have been wrong. But I have heard it suggested, in effect, that secret Mormon ceremonies represent a kind of unpublished Mormon scripture. Apologists don't necessarily have to spill all the beans, but they may at least want to address this concern in some way, perhaps just by explaining the kind of doctrinal authority which is attributed to the ceremonies, without describing their content.

Re: the loose definition of doctrine, I agree. That's something that we should be more precise about. As I mentioned above, I wish we were more willing to limit ourselves, when speaking of doctrine, to what JEsus calls "my doctrine" in the Book of Mormon

The Book of Mormon makes it pretty clear that you HAVE to limit yourself to what He calls "His doctrine." Because he says that if anyone teaches more or less than what he calls his doctrine, they are of evil. Kind of really puts a damper on the majority of Mormon doctrine. That sort of rules out any possibility that the temple rituals are doctrinal. Eternal marriage, then, clearly becomes not doctrinal either. Because this stuff is all "more than" the doctrine, as Christ declares it.

"explaining the kind of doctrinal authority which is attributed to the ceremonies"

I don't think there is anything official, not that I know of at least. My sense is that the temple and its ceremonies are viewed in high regard and as something very sacred and precious by the majority of members, a smaller group that don't find it of much worth, and then a smaller subset that find it off-putting. I would say the leadership endorses the first view. Where some people find discrepancies with what they feel is taught in the temple with what is taught currently by the leadership, it has been my experience that the current teachings publicly taught by leaders takes precedence in every case that I'm familiar with. I would also guess that most people either don't see discrepancies or don't focus on them if they feel there might be any.

As it is a sacred subject for me and most Mormons, I appreciate you being careful. And I wish to do the same, while still trying to be helpful to your inquiries.

Aside from the teaching that further ordinances are necessary to receive the highest blessings from God, such as receiving an endowment and sealing of a marriage and family for eternity, which are also taught frequently outside of the temple, I'm having a hard time imagining what other doctrines are really introduced in the temple at all. While the format of the ceremony might stand in contrast to other forms of worship, particularly new testament and even Book of Mormon most common forms of worship, if we include the old testament the elements and theology in almost all instances are taken directly from the accepted cannon of the church, ranging from tabernacle/temple washing and anointing / or priest and kingship practices of the old testament, to elements of creation found in the pearl of great price, to doctrines of atonement and restoration found in the Book of Mormon and the Doctrine and Covenants. Perhaps there is an implied theology of ascension and returning to the presence of God, that was more expressly taught at the end of Joseph Smith's life. But I don't think such doctrines are kept from the public, although they might not be taught with the same frequency in favor of more practical here and now teachings.

That's my take at least.

"My sense is that the temple and its ceremonies are viewed in high regard and as something very sacred and precious by the majority of members."

It is more than that they are held in high regard, and as something sacred. Without the ordinances, there is no eternal life for humankind.

While the format of the ceremony might stand in contrast to other forms of worship, particularly new testament and even Book of Mormon most common forms of worship, if we include the old testament the elements and theology in almost all instances are taken directly from the accepted cannon of the church, ranging from tabernacle/temple washing and anointing / or priest and kingship practices of the old testament, to elements of creation found in the pearl of great price, to doctrines of atonement and restoration found in the Book of Mormon and the Doctrine and Covenants.

You need to understand the proper relationship between the Old and New Testaments. Joseph Smith didn't get this. Christ is the end of the law to all those who believe in him. In this commandment, love one another, you have fulfilled the entirety of the law. The old law became obsolete. This is all New Testament doctrine. There is no need to have a "restoration" of "all" things. Not all things needed to come back for a second act, as Joseph Smith taught. Jesus fulfilled the law.

EBU,

I understand the sentiment you express, and I think it is a reasonable belief.

On the necessity of the restoration of the temple and many of the rites thereof, I personally don't believe all of it pertained only to the old law of Moses. In places like Ezekiel and other places, I see prophesies of the necessity of the restoration of the temple in the last days. I see Christ's actions in the temple, and Peter's and leaders' subsequent actions post Christ's death as evidence that they too believed that these things were not simply done away by Christ. I believe Joseph Smith understood a thing or two about these principles.

Again, not to knock your belief, I see how that can be a reasonable conclusion. And you're right, I meant the doctrines presented in the temple are held in high and sacred regard. Yes, I too believe without the ordinances there cannot be a fullness of salvation. Which I guess at the same time the doctrine of vicarious work for those who didn't get that opportunity is likewise such an important belief to me, and I believe to Mormons generally.

If you pay attention to the endowment narrative, it's pretty clear that it is not to be taken literally. Not that that stops a lot of people from doing so anyway.

If you pay attention to the endowment narrative, it's pretty clear that it is not to be taken literally. Not that that stops a lot of people from doing so anyway.

JKC said…

None of what you said establishes that inerrancy is a doctrine of the church.

You weren't discussing whether or not it is church doctrine. You stated:

"Maybe there are some Mormons who claim that the Book of Moses in inerrent. I've never met one."

Which I am pointing out is extremely disingenuous. If you'd like proof, in your next Priesthood or Sunday School class, point out that there are errors in the Book of Moses and ask how many class members agree with you. I'm sure you would then meet several Mormons who claim that the Book of Moses is inerrent (more than likely a majority of the class). Some in the class will likely wonder if you are "struggling with your testimony."

You also mentioned in an earlier post that:

"the fact that it was canonized and the rest of the translation was not is really more the result of historical accident than a conscious decision that the Book of Moses is somehow more reliable than the rest of the JST."

If it was an historical accident, why hasn't the accident been fixed?

James,

Your "green-eyed stranger" scenario is interesting, but incomplete and not representative of the process of conversion as I understand it.

First, an interest in only green-eyed strangers would seem arbitrary. Why that type of person over all others? Would they posess some quality others don't?

Second, the process described in Alma 32 is a process, not usually a head-over-heels type of thing.

Third, you do have to be in a "peculiar" state of mind, if you will. You need to be receptive, humble, and intent on following the promptings you receive. Why should the Lord reveal anything to someone who is only curious?

Also, what if there is only one truly green-eyed person out there, and all others apparently so are only wearing colored contact lenses?

JKC said:

"I was taught more than once in BYU religion classes that, if for no other reason, the very nature of human language itself means that inerrency cannot be a fact of latter-day scripture. At least one BYU religion teacher taught that "as far as it is translated correctly" is implied to apply to the Book of Mormon as well"

I wonder if this is a generational thing? It's been more than 20 years since my religious educational experience. I wonder if this is indicative of a distancing of the church away from Joseph Smith's canonized doctrinal "translations." The Internet and scholarship had not yet caught up with the Book of Abraham when I was in school, and there was less need to cover bases.

I'm wondering if, when you discussed possible errors in scripture, even in the BoM, specific examples of errors were brought to light or was it left to you to find them yourself? Any official, general-conference from-the-pulpit discussion of errors in the BoM I have ever heard were in regards to spelling, punctuation, & grammar, not doctrine or practice. It seems the acceptance of inerrancy is extremely limited.

Anonymous, it might be a generational thing. My BYU experience was about 10-15 years ago. But are you sure that scholarship had not yet caught up with the Book of Abraham? A lot of that stuff was pretty well covered in the 1980s, wasn't it? (Of course it took longer for teh scholarship to trickle down.) Or it might be a regional thing, because I've had discussions about this topic several times in Elders Quorum lessons and nobody has ever expressed shock or surprise at the idea that scripture, being expressed in human language, is not inerrant. So no, my statement is not "extremely disingenuous." Maybe your experience is different, but my point is simply that your experience is not universal, and from my limited perspective, my experience has been just the opposite.

As to whether specific errors in the Book of Mormon were discussed in my BYU classes, I honestly don't remember. I certainly learned about them at that time, but I honestly can't remember if they were brought up in class or if I read about them on my own outside of class. I think the teacher just sort of generally referred us to the work of Royal Skousen as a source for all the Book of Mormon changes. I vaguely remember that he might have pointed out the changes in 1 Nephi from "the Eternal Father" to "the son of the Eternal Father," but honestly, I may have read that on my own after class, I just don't remember.

When I said "historical accident" I did not mean it in a pejorative sense, as a problem that needs to be fixed. The interesting thing about the JST and the Pearl of Great Price is how the church accepted the Pearl of Great Price basically unquestioningly, because it was presented to the church and canonized in late 1800s, while the church took a much more skeptical view toward the JST/Inspired Version, because it came from the Reorganized Church, given the historical distrust between the two churches, not realizing that the JST and the Book of Moses came from the same source. The JST became much more widely accepted as authentic in the 1980s, and much of it was eventually incorporated as footnotes in the LDS edition of the KJV, but it is still not canon.

Does this need to be fixed? I'm not so sure. The fact that something is in the canon does not necessarily mean that it is perfect. The Song of Solomon is technically part of the canon, but must church members probably agree with the JST that it is not inspired (to the extent that they have even read it). I think we can accept that the Book of Moses is part of the canon, and at the same time, recognize that it comes from the same source as the JST, which we have accepted as often inspired, but not inerrant.

I suppose you could ask the same question about why has the Bible not been updated to reflect, for instance, the dead sea scrolls. The fact that the Bible has the version it has rather than some other version often a historical accident, rather than a conscious decision that the version we have is the most accurate version. But I don't think that means that we need to change the canon to reflect that, we can just let it inform our understanding of the canon.

Which I guess at the same time the doctrine of vicarious work for those who didn't get that opportunity is likewise such an important belief to me, and I believe to Mormons generally.

Why would you need to do vicarious work for those who died with the law? Moroni says that to baptize people without the law is a dead work, and is mockery before God.

"For behold that all little children are alive in Christ, and also all they that are without the law. For the power of redemption cometh on all them that have no law; wherefore, he that is not condemned, or he that is under no condemnation, cannot repent; and unto such baptism availeth nothing— But it is mockery before God, denying the mercies of Christ, and the power of his Holy Spirit, and putting trust in dead works."

Why is baptizing dead people who may have died without the law not a "dead work?" (No pun intended.)

This is the Mormon conundrum. If all are alive in Christ before they receive the law, and the power of the redemption comes on all such people, then receiving the law brings the person into condemnation. Missionary work is the work of the devil. They'd be better off left alone.

I meant…"died WITHOUT the law…" Sorry.

@bearyb:

The arbitrariness of letting eye color determine a spouse was supposed to be analogous to the arbitrariness of letting a feeling determine a faith. Eye color isn't actually a very good guide to any of the things that make a good marriage; neither is it good, it seems to me, to base faith on a brief feeling.

The reason for the arbitrary decision was also part of my analogy. Marrying the next green-eyed stranger is a terrible way to get a good marriage, but a good way to stop having to search for a partner (which can be very stressful). So deciding to just go for green eyes means prioritizing an end to the agonizing search, over finding the elusive prize. In the same way, trusting your feelings of assurance as a personal answer to prayer seems to me like a terrible way to find truth, but a good way to stop having to look for truth. So merely accepting Moroni's challenge seems to me to imply a strong will to believe.

Among the very religious people I've known (very few of whom have been Mormons), a fair proportion have seemed to me to be people who craved certainty. Often they would say explicitly that they believed what they did because the alternative was to be uncertain about important questions. They took for granted that this alternative was unthinkable. When a big part of why you have faith is just in order to have faith, it may not take much to bring you to faith. Where there's a will to believe, there may well be a way.

EBU,

All save Christ, who have developed the mental capacity to be capable of sin, have fallen to sin. Since all knowledge and all things have not been revealed, I imagine no person has received all law. Conversely, all places and times have some degree of the light of Christ and some form of law by which they can do right or wrong. Having sinned, they can repent, and baptism becomes applicable for salvation.

That's my understanding.

Mormon conundrum solved 😉

And 8-years old is the universally-applied standard to determine who is accountable and who is not. Sounds as random and arbitrary as declaring all human beings wicked and condemned upon birth.

All save Christ, who have developed the mental capacity to be capable of sin, have fallen to sin. Since all knowledge and all things have not been revealed, I imagine no person has received all law. Conversely, all places and times have some degree of the light of Christ and some form of law by which they can do right or wrong. Having sinned, they can repent, and baptism becomes applicable for salvation.

Steven,…and that is what you think the Book of Mormon is telling us?

EBU,

I believe that is the truth, and it is the truth I glean from spirit of that passage. Perhaps Moroni didn't know of the doctrine of vicarious work, and he was trying to reconcile the issue of those who died without the opportunity in the way you interpreted it. Even if so, I feel truth in what he speaks and it's true enough anyway, and now with expanded knowledge on the subject (vicarious work) the truth is even clearer in my mind. I'm not as concerned about what was thought or said as much as what is. I don't feel bound to former understanding when more light is shed on the subject.

I think 8-years-old is a revealed generalized standard, I don't find it arbitrary, but I agree that when an individual becomes truly accountable and capable of sin will vary person to person, likely around that timeframe. Or in the case of those who do not fully mentally develop, perhaps many in such cases never reach that standard of capability and therefore accountability for sin, for whom I think this passage becomes very relevant.

In my estimation where there is sin, it stands to reason that repentance is available through Christ, and if repentance then baptism also to open the doors to salvation.

Steven,

Mormonism has crafted for itself several escape routes out of any difficult situation. One of these escape routes is this notion that "not all has been revealed." Anytime something doesn't add up, or scriptures are in conflict, or words of prophets are in conflict, you can throw down that card and….voila!….the church is true!

Uchtdorf recently presented us with a nice version of this when he said the Restoration is an ongoing process. You do realize what this means, I hope.

It means that you cannot really have a testimony of Truth, because the ongoing nature of the Restoration means that this Truth may end up being modified, or even changed, later on. And indeed we see many examples of this happening.

The only thing you can have a testimony of, then, as a Mormon is that that leaders of the church are the people you need to obey, because they are entrusted with the task of revealing this Restoration as we go along. You don't need to believe in Truth. Just believe in the authority of the source.

That is it.

By the way..Joseph Smith never saw it as an ongoing Restoration. After the Kirtland Temple dedication, he declared that he had finished all that God need him to do. The church was now in its proper form. The Restoration, basically, was over. Of course, he hadn't yet revealed temple marriage, endowments, initiatories, proxy ordinances, etc…

Haha, yes good example. You think you know everything, finished what you need to do, and then wham, God says not so fast, there's still more. Happened to Joseph Smith, has happened to me frequently, and I expect it happens to many people.

I think the reality is that Pres. Uchtdorf didn't come up with that concept, it's been with us nearly from the beginning, our Article of Faith #9 from Joseph Smith, "We believe all that God has revealed, all that He does now reveal, and we believe that He will yet reveal many great and important things pertaining to the Kingdom of God."

Yes, I can see how trying to hold a Mormon to a particular doctrine or scripture might be a frustrating pursuit. I guess it goes back to the idea that we just don't see scripture or teachings as inerrant, but ever expanding until that day that all things are revealed. In my mind that seems far distant. For example, we have an expanded version of the afterlife from the idea that there is a heaven and hell to now an understanding of many degrees of salvation / glory. But how much do we really know about the afterlife and everything that happens there? My impression is that we still understand relatively very little.

However, going back to comparing this to truth as understood through the means of science, just because we don't have a theory of everything doesn't make the discoveries we have made irrelevant or useless. Newtonian physics still has it's place, Relativity and Quantum Mechanics are very useful and insightful although apparently incompatible and thus suggesting we are still waiting for a more complete answer. That doesn't mean I have to throw out everything.

And while I respect leaders and have a testimony for myself that they are chosen by God to fill their stations, ultimately it is truth, revelation, and confirmation that I receive through the Holy Ghost that I rest my faith on. I believe God love his children, I believe He wants to speak to them, I feel I have received personal knowledge from Him, and I look forward to not stopping but continuing in my pursuit and acquisition of further light and knowledge that I might be a more loving person to my family, friends, and fellow-man and have joy with and in one another.

EBU, Quotes from Pres. Uchtdorf and the Book of Mormon, knowledge of the endowment, etc. Were you once a member of the LDS Church? Or just someone who's invested a lot of time learning about us?

James, you've mentioned your own religion, do you belong to a particular denomination?

Just curious, hope it wasn't rude that I didn't ask you both earlier.

I don't mind being asked. I mentioned in another thread that I've been Anglican (Episcopalian, for Americans) most of my life, but have been in a Lutheran congregation for the past ten years — and haven't found it all that different. I see myself as pretty traditional in belief, but that's the so-called 'high church' tradition that's not far from being a sort of Roman Catholicism without the Roman part. In particular I'm not big on scriptural authority. I'm prepared to say the Bible is wrong in some places — and that in many places its real, inspired meaning is not the most obvious one.

In principle I'm willing to talk further about my own beliefs, just in the spirit of comparing notes; but I don't think that anyone should particularly care about what I believe. Dammit, Jim, I'm a physicist, not a theologian.

Haha, love the reference, yes I was mostly just curious. I know of several Mormon bloggers who really appreciate the Anglican tradition (see here for example), and Joseph Smith was really taken by the Luther Bible.

@ EBU

There is no need to have a "restoration" of "all" things. Not all things needed to come back for a second act, as Joseph Smith taught.

What, then, is the meaning of Acts 3:21?

@ EBU

"For behold that all little children are alive in Christ, and also all they that are without the law. For the power of redemption cometh on all them that have no law; wherefore, he that is not condemned, or he that is under no condemnation, cannot repent; and unto such baptism availeth nothing—"

This is the Mormon conundrum. If all are alive in Christ before they receive the law, and the power of the redemption comes on all such people, then receiving the law brings the person into condemnation. Missionary work is the work of the devil. They'd be better off left alone.

Please read the verse a little more carefully. Taken together with an eariler verse (10) which says

Behold I say unto you that this thing shall ye teach—repentance and baptism unto those who are accountable and capable of committing sin;

it would seem that anyone who is "accountable and capable of committing sin" would be considered "in the law." You don't have to have been visited by Mormon missionaries to be capable of committing sin, and hence in need of baptism.

What, then, is the meaning of Acts 3:21?

It's the end of the world when all things are finally made whole and complete once again in Christ. Not just us and our physical bodies, but the whole creation. Acts 3:21 says the Heavens will receive Christ up UNTIL the restoration of all things. I don't believe that Jesus coming to Joseph Smith in the woods is the coming of Christ that ushered in the period of the restoration of all things. This is not talking about the restoration of a church or of an authority. It is talking about the restoration of ALL things.

Romans 8

For I reckon that the sufferings of this present time are not worthy to be compared with the glory which shall be revealed in us. For the earnest expectation of the creature waiteth for the manifestation of the sons of God. For the creature was made subject to vanity, not willingly, but by reason of him who hath subjected the same in hope, Because the creature itself also shall be delivered from the bondage of corruption into the glorious liberty of the children of God. For we know that the whole creation groaneth and travaileth in pain together until now. And not only they, but ourselves also, which have the firstfruits of the Spirit, even we ourselves groan within ourselves, waiting for the adoption, to wit, the redemption of our body.

Ephesians 1

Having made known unto us the mystery of his will, according to his good pleasure which he hath purposed in himself: That in the dispensation of the fulness of times he might gather together in one all things in Christ, both which are in heaven, and which are on earth; even in him: In whom also we have obtained an inheritance, being predestinated according to the purpose of him who worketh all things after the counsel of his own will: That we should be to the praise of his glory, who first trusted in Christ. In whom ye also trusted, after that ye heard the word of truth, the gospel of your salvation: in whom also after that ye believed, ye were sealed with that holy Spirit of promise, Which is the earnest of our inheritance until the redemption of the purchased possession, unto the praise of his glory.

1 Corinthians 15

For the perishable must clothe itself with the imperishable, and the mortal with immortality. 54 When the perishable has been clothed with the imperishable, and the mortal with immortality, then the saying that is written will come true: “Death has been swallowed up in victory.

@James Anglin:

I equated eye color in your analogy to represent general faith traditions (Christian, Islam, Taoism, etc.). A person might decide to follow one of these for various reasons: First introduction during a time of need; An individually favorable comparison to the others; What they are used to; Any of a number of other reasons or a combination of reasons.

I agree that it would not be good to base a faith decision on a "brief feeling." That is one reason I find Alma's "experiment" approach beneficial. It is also biblical to learn the truth of something by following it, or doing it.

In the LDS tradition, the search for truth is never "over." It is not a destination, but a continuing journey. In fact, chapter 32 of Alma is more a chapter on how to gain knowledge than on how to excercise faith. If you were to ask any number of LDS adherents, I'm sure they would generally agree that each of them is in a different place on the path. And accepting Moroni's challenge implies more than just a strong will to believe, but also a strong will to act.

The choosing of a marriage partner based on eye color or any other physical quality is generally a poor way to do it. And even if they were to possess all the qualities you think you might want in such a match (has that EVER happened?) and had an exceptional courtship and beautiful wedding, there is still no guarantee that the marriage will last for any given period of time.

So while the search for a partner may have ended, the work will have only just begun (yes, I'm a Carpenter's fan).

@James Anglin:

I'm not sure if what you meant by your comment was that of the Mormons you have known very few were religious, or that you have known very few Mormons.

Either way, religious or not, I figure most people crave certainty.

On one hand, the LDS Church does claim certain knowledge about "important questions," as you put it. But on the other, it arguably raises more questions than it answers. There is probably some disagreement about the relative importance of a lot of such questions.

You do raise a good point about a possible reason to have faith – for it's own sake. But the LDS approach is not so passive. The cost of discipleship can be quite high at times. There are, however, many who will tell you that the benefits of dedicated service more than compensate.

@EBU:

Mormonism has crafted for itself several escape routes out of any difficult situation. One of these escape routes is this notion that "not all has been revealed." Anytime something doesn't add up, or scriptures are in conflict, or words of prophets are in conflict, you can throw down that card and….voila!….the church is true!

Obviously, we don't see it that way. What you might call a difficult situation we may not see as a problem at all. Or, if there is confusion, we might well say that we don't yet have a complete understanding. Aren't there things in your life about which you wish you had a better understanding? How can you live a happy life without having all the answers?

Now, what would be a difficult situation would be our claiming to have living prophets among us, and then saying that they don't really matter because we already know all we need to know.

I think a truly difficult situation would be to have living prophets among us who have to constantly revise the words of past living prophets. It sort of looks like there might not be any living prophets at all.

Joseph Smith taught that Jehovah was the Father. Brigham Young taught that Adam was the Father. James Talmage says Jehovah is Jesus. The other leaders say, "Jim…put that in writing." And voila! The 1916 Doctrinal Exposition on the relationship and identity between the different members of the Godhead.