I’ve been puzzled several times by the mysterious ignorance of Champollion in the early nineteenth century — not among ordinary Americans of that day, but among modern scholars writing about the Book of Abraham. While a review of newspapers and books in the 1830s to 1840s (and before) shows many references to the breakthroughs associated with the Rosetta Stone and Champollion’s work to decipher it, and while the rise of Egyptomania in the 19th century was intimately associated with the fascination with Egyptian stimulated by news on the progress in deciphering Egyptian, some modern scholars discussing the Book of Abraham seem to feel that news about Champollion was only available to elite scholars, not ordinary people like, say settlers in Ohio in 1835. Their theories on the origin of the Book of Abraham as a product of Joseph’s environment rely on Egyptomania without knowledge a key factor behind Egyptomania, the phonetic nature of Egyptian and the potential for its decipherment.

The theory that Joseph was translating as many as 200 words from a single simple character of mystic Egyptian is essential for typical critical narratives about the origins of the Book of Abraham, while some of us argue that Joseph’s prior comments regarding the gold plates and the Book of Mormon’s information on the nature of its written language systems (called reformed Egyptian by the time Mormon was writing) already would seem to rule our the ignorant belief that one character could give vast mountains of text when unlocked with priestly oracular gifts.

Examples of the puzzling view of “American Egyptomania without Champollion” from scholars within the Church are found in two volumes of the Joseph Smith papers, which tell us that knowledge of Champollion was not widely available in the US in the 1830s and 1840s, and in a recent lecture from Terryl Givens that tells us Joseph subscribed to the outdated 17th-century views of Kircher, wherein one character could convey a great deal of information. I discuss these in my recent paper at The Interpreter on the Joseph Smith Papers’ volume on the Book of Abraham, a book that I consider to be a wonderful resource with some serious flaws. One example from the opening pages of the reviewed volume follows:

Even after Champollion’s groundbreaking discoveries, though, some

continued to assert competing theories about Egyptian hieroglyphs,

whether they rejected Champollion’s findings or were ignorant of them.

Indeed, in America in the 1830s and 1840s, Champollion’s findings were

available to only a small group of scholars who either read them in

French or gleaned them from a limited number of English translations or

summaries. (The Joseph Smith Papers, Revelations and Translations, Volume 4: Book of

Abraham and Related Manuscripts, ed. Robin Scott Jensen and Brian

M. Hauglid (Salt Lake City, UT: Church Historian’s Press, 2018), Volume 4, p. xviii.)

If one looks at publications from that era, it’s easy to see that knowledge about the story of Champollion and the Rosetta Stone was common across the US, not just reserved for elite scholars. So where did the idea of Egyptomania without knowledge of Champollion come from?

The source may be the one professor quoted most frequently in the Joseph Smith Papers volume on the Book of Abraham. Not Hugh Nibley, the most prolific and influential scholar to have tackled the many issues related to the documents and information in the Book of Abraham volume if the Joseph Smith Papers — he is cited a total of zero times as if he and his ideas did not exist. Rather, the most visible and influential scholar based on citations in the Joseph Smith Papers volume on the Book of Abraham would be Dr. Robert K. Ritner, the hostile critic of Joseph Smith. His book, cited over 50 times in the JSP volume, is The Joseph Smith Egyptian Papyri: A Complete Edition, P. JS 1–4 and the Hypocephalus of Sheshonq (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2013); Kindle edition. (The Joseph Smith Papers, Revelations and Translations, Vol. 4, cites the 2011 version printed by the Smith-Pettit Foundation in Salt Lake City.)

In his introduction, Ritner writes:

Copying the texts with the assistance of select “scribes,” Smith quickly recognized several biblically-themed compositions within the papyri, eventually including the Book of Abraham (P. Joseph Smith 1), the record of Joseph of Egypt (P. Joseph Smith 2 and 3) and a tale of an Egyptian princess Katumin or Kah tou mun (P. Joseph Smith 4). Only the first of these translations was ever published, beginning in serialized excerpts during 1842, well before Jean François Champollion’s correct decipherment of Egyptian was generally known in America.3

His footnote #3 gives the evidence he cites to support the proposition that in 1842, new of Champollion’s decipherment of Egyptian was not generally known in America. Let’s take a look:

3…. Champollion’s discovery was reported in the United States in the New York Herald, December 28, 1842. For its potential restraint on Smith’s future translations, see Brodie 1945, pp. 291–92 (regarding the falsified “Kinderhook plates” supposedly found in an Indian mound). Smith noted in his journal that he “translated a portion” of the plates, which he thought recounted the history of a person buried in the mound, “a descendant of Ham, through the loins of Pharaoh, king of Egypt.” The translations of this hoax were not published.

He doesn’t exactly say that this was the actual first announcement to the general public, but obviously he is implying that this 1842 publication somehow shows that Champollion’s breakthrough was not generally known at that time.

I was quite surprised to read Ritner’s claim and his supporting footnote, for it took only a few minutes of searching at Newspaper.com to find many interesting stores from the 1830s or earlier treating the Champollion story as if that were already common knowledge (an issue I explore much more fully in my article at The Interpreter). Something is wrong here. So let’s take a look at the reference cited by Ritner. It must say something that convinced the grand scholar that Champollion was unknown before that story came out. Perhaps it mistakenly claims to be the first publication of the news out of some kind of editorial slip.

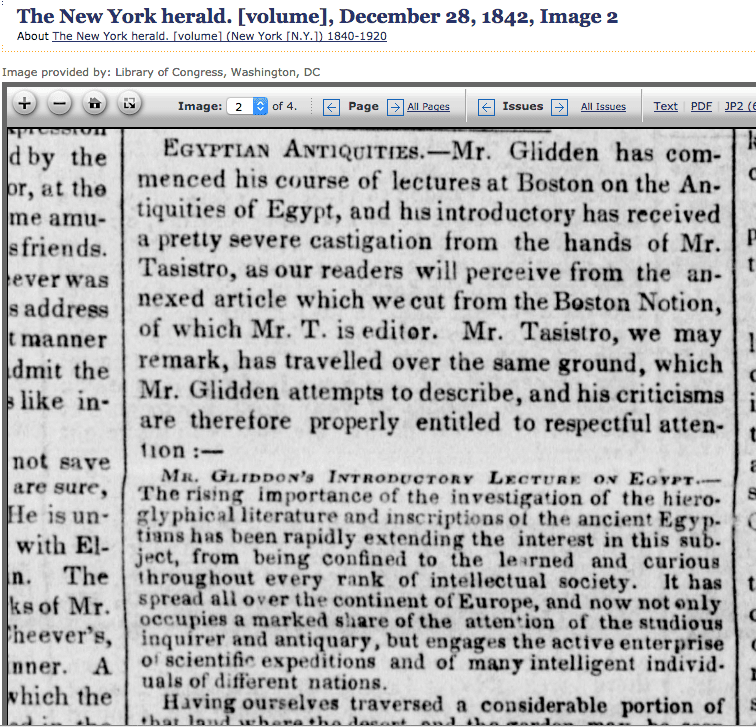

Fortunately, readers can see the source Ritner cites at the Chronicling America website:

Here is the text:

EGYPTIAN ANTIQUITIES. — Mr. Glidden has commenced his course of lectures at Boston on the Antiquities of Egypt, and his introductory has received a pretty severe castigation from the hands of Mr. Tasistro, as our readers will perceive from the annexed article which we cut from the pages of the Boston Notion, of which Mr. T. is editor. Mr. Tasistro, we may remark, has travelled over the same ground, which Mr. Glidden attempts to describe, and his criticisms are therefore properly entitle to respect attention:–

MR. GLIDDEN’S INTRODUCTORY LECTURE ON EGYPT–

The rising importance of the investigation of the hieroglyphical literature and inscriptions of the ancient Egyptians has been rapidly extending the interest in this subject, from being confined to the learned and curious throughout every rank of intellectual society. It has spread all over the continent of Europe, and now not only occupies a marked share of the attention of the studious inquirer and antiquary, but engages the active enterprise of scientific explanations and of many intelligent individuals of different nations.

Having ourselves traversed a considerable portion….

Curious indeed! For an article that supposedly shows that Americans in late 1842 still hadn’t heard of Champollion, note that Champollion is introduced only with his last name — as if no introduction were needed. And no introduction is given. This is not an announcement of Champollion’s accomplishment or story, but news about criticism on a lecture given by a third party on the antiquities of Egypt. The background story of the Rosetta Stone and Champollion are assumed to be well known to the readers.

In other words, Ritner has completely misread this reference. It undermines his assertion. Other scholars appear to have accepted his pronouncement and have built upon it, adding such touches as the assertion that only a few French-reading elites might have been aware of Champollion’s story — just as only a few elite Ph.D.s in astrophysics today are aware that Neil Armstrong walked on the moon.

In Ritner’s defense, I can see how the emphasis on Europe in the article might lead a casual reader to conclude that the explosion of knowledge of and interest in Champollion’s work was a European thing only. But that misreading is unjustified. The critic being cited, Mr. Tasistro, may have been Louis Fitzgeral Tasistro, an Irishman who came to the US four or five years before this article was written. His great familiarity with widespread European interest in Champollion must not be interpreted as evidence against such interest or awareness in the States. Americans may not have been as intensely interested or as well informed as Europeans in general, but flame of American Egyptomania surely was not burning bright without the fuel of Champollion. The reference cited by Ritner simply does not support his claim and implicitly contradicts it.

Many myths have similar pedigrees. One elite scholar makes an unsupported assertion, and others assume that the elite one must be right and accept the pronouncement or embellish it a bit, and off we go. It’s nice today that we often have easy access to many sources so that we can check and see for ourselves.

Update, Aug. 25, 2019: For further evidence regarding knowledge of Champollion among the early members of the Church, see my latest post: “Is There Direct Evidence that the Early Saints Had Heard of Champollion?,” Aug. 25, 2019.

Jeff, this is an example of a strengthening trend among Latter-day Saint scholars to agree uncritically with the critics, even adopting positions they know or should know are inaccurate. Sometimes they just leave readers with the wrong impression, but do so deliberately. There is certainly incentive among LDS scholars to do this, as they can gain approval from the broader, non-LDS academic community and increase their opportunities to publish.

Funny, hopefully this isn't taken the wrong way (can't afford an attorney ;)), but I've often wondered if Robert lets his peers at Lighthouse Ministry do research for him.

It's fine to give needed attention to critics, but it's sad that JSPP editors would refer to RR 50 times, and not Nibley. Nibley is one of the greatest scholars of all time.

True, Ritner's additional translation of the Hor scroll may be more accurate (as expected, since that is his occupation and it's 50 years later), but we have better from Rhodes and already knew what the papyri said anyway. So, it may be that Robert has added himself to the conversation, along with misinformation and additional encouragement for hate groups, but I can't think of reasons to quote him unless we are comparing Egyptologists' translations of papyri…again.

On the other hand Nibley educated us. He opened doors, taught us to respect Abraham and learning and to reject riches and pompousness. Nibley tied things together with world history, connected us in ways that bettered our so called "modern" lives. He inspired love, reason, compassion, humility, and so on and on.

Nibley opened minds, Ritner closes them.

Still, gotta love him.

I could write 2000 words about the word charity. I could do it for any meaningful Gospel word. How could you not probe an eternal reservoir of language in describing atonement and so on.

Now I'm not saying the book of Abraham was translated that way, but I think there's no reason why a symbol couldn't come with all kinds of language that even those fluent in it can't describe.

Jeff says:

“Ritner has completely misread this reference.”

I think this should be rewritten “Jeff has completely misread this reference.” Two examples as follows:

Example 1

“note that Champollion is introduced only with his last name — as if no introduction were needed. And no introduction is given.”

Let’s see who else in the folio doesn’t include mention of a first name—as if no introduction were needed. Do you suppose the readership is intimately familiar with each of these other names?

Arnold

Webb

Countess of Dysart

Postmaster General

Parson Cheever

Elder Knapp

Mr Davis

Mr Cheever

Mr Andrews

Mr Glidden

Mr Tasistro

Dr Young

Kalproth

Le Chevalier de Palin

Commander McKenzie

Lieutenant Gansevoort

M. C. Perry

R. W. Lincock

C. W. Hayes

A. Delonde

O. H. Perry

J. W. Wales

B. P. Browning

Mr Morris

Mrs Hunt

Mr Forrest

Miss Duff

M. Bley

Mrs Loder

Mr Horn

Mrs. Sutton

the Brahams

T. B. Clayton

Alderman Davis

Alerman Purdy

Alderman Smith

Alderman Davies

Alderman West

Alderman Lee

Alderman Crolius

Alderman Hatfield

Alderman Woodhull

Alderman Underwood

Justice Matsell

Justice Merritt

Recorder Tallmadge

Alderman Leonard

Alderman Bonnell

Justice Taylor

Alderman Gedney

Messrs Sheiffelin

Alderman Atwell

Ald. Scoles

Alderman Brown

Mr. Whiting

W. Dodge

Barnum

Nellus

Jenkins

Diamond

Young

Judge Conrad

Judge Barton

McNamee

Gov McDonald

Mr Habersham

Officer Stephens

Thompson

Capt. Quackenboss

Morris

Dr Elliott

Dr Castle

a lady

a gentleman

Dr M O’Regan

W. S. Richardson

Obviously a full name isn’t a requirement to be mentioned in this folio. Second example to follow

“The background story of the Rosetta Stone and Champollion are assumed to be well known to the readers.”

So well known that they recount to the readers the background story:

“the study of hieroglyphics has been very common in England, ever since the publication of Champolion’s complete grammar of the Coptic language, in which he proves that this is the language used in the inscriptions on the ancient Egyptian monuments. The same indefatigable individual has also compiled a Coptico-Egyptian dictionary, contained in three quarto volumes, and comprising the three distinct dialects, viz: the Thebaic, Memphitic, and Heptanomiic. . .”

Jeff goes on to claim:

“Americans may not have been as intensely interested or as well informed as Europeans in general, but flame of American Egyptomania surely was not burning bright without the fuel of Champollion. The reference cited by Ritner simply does not support his claim and implicitly contradicts it.”

Please refer to the following quote from the article and see if it does what Jeff claims (emphasis added by me)

“Every thing connected with the history of those remote ages. . . possesses a mysterious interest which is now beginning to be much more generally felt than heretofore.”

Jeff also states that:

“This is not an announcement of Champollion's accomplishment or story, but news about criticism on a lecture given by a third party on the antiquities of Egypt. The background story of the Rosetta Stone and Champollion are assumed to be well known to the readers.”

What he fails to mention is that the writer is discussing a presentation by a Mr. Gliddon (Glidden? two different spellings in the article) regarding Egyptian antiquities, in which he is presenting information as his own that, according to Tasistro, was “in the hands of every European scholar.” Glidden was an apparent plagiarist who was called out by Tasistro. The plagiarist’s hope to succeed lies in the fact that those who are receiving the information presented 1) aren’t familiar with it, and 2) don’t know the information comes from a source outside of the presenter. Why would Glidden be so hopeful of success if “The background story of the Rosetta Stone and Champollion are. . . well known”? Tasistro can so readily recognize the deception because he was “ Louis Fitzgeral Tasistro, an Irishman who came to the US four or five years before this article was written.”

Ok/not Ok, looks like you kinda have a point this time. Ritner introduces a Jean François Champollion, who probably wasn’t known in the Americas. Same with that guy "Dr. Young", who everyone in Europe agrees was a contributor to deciphering Egyptian, but here it was so confusing. There were so many Champollions running around deciphering things that members of the Church of Jesus Christ couldn’t have possibly known that exact Champollion. In fact, it was so confusing that the papers would say things such as “The Ruins in Wisconsin…by what Champollion it was deciphered, we are not informed…” Constantine republican. 1837 They had no idea which or who. Probbaly because most Champollions simply went by “Champollion”, but several were M. Champollion, some were “the celebrated Champollion”, some spelled it with only one l, some worked with a Dr. Young (but it seems that the discussion of Ritner’s Champolion actually had insulted a guy simply named Young!! Or was it the other way around?,s o confusing…). Some Champollions led expeditions to Egypt, one died in 1832, and it was said that “…announces the death of the celebrated Champollion…the scientific world sustains an irreparable loss…” Phenix gazette (Alexandria [D.C.]), April 24, 1832). One paper published extracts from a letter written by a Champollion who used 2-3 of the Champollion first names “Extract of a letter from M. Champollion, the celebrated French hieroglyphist” (what Champollion could possibly figure out who that was in 1828?). Even more confusing, another 1838 paper refers to leaving something for “future Champollions” to decipher. And, probably most confusing for Joseph Smith, The New York herald, April 03, 1842, mentions Champollion and Young (offended Dr. Young or Young the co-decipherer? Maybe those future Champollions will decipher that one :)) near the publication of Joseph’s Fac. 1 and BofA (good thing he didn’t look at that number, or he never would have dared publish the next installments). No wonder they had to clear that up in December of 42…. : )

Holy crap, Joe, stop calling every anonymous commenter "ok/not ok." You look like a fool assuming Jeff only has one critic. There are scores of us. Also: learn to edit and format your wall of text comments! It's unbearable!

“most confusing for Joseph Smith, The New York herald, April 03, 1842”

Do you suppose Joseph had a subscription to the New York Herald in 1842? Do we have record of him, any of his cohorts, or even anyone in the Mormon community referencing Champollion or his work? Wouldn’t you assume someone would perhaps mention it in passing, especially considering the similarities you are inferring between their work? How about anyone west of Appalachia? On the lips of everyone?

You would suppose someone in the community would refer to Joseph as the Mormon Champollion being as it was such a common reference in the vernacular. Anything?

This comment has been removed by the author.

I'm just a maintenance guy in a food Plant (but I feel it's an honest living), so I don't know much about 19th C. Newspaper publishing but I'd say there's about a 99% chance that Joseph read the article where they talked about Champollion. The article was about President Smith and was quite positive. They were hoping that he could help stop the downward slide of our country. You, of course, fight against all that (as in PAGAN= People who fight Against Goodness and Niceness ;)–was that from an Eddie Murphy movie?). Also, I would think they had to borrow Hedlock's printing plate for Facsimile 1, but maybe there was some other way?

Should we ask the smart guy?

Jeff, if you check this, what do you think? Wouldn't they have to borrow the plate to publish fac 1 in a newspaper?

Either way, there's little chance that Joseph Smith and Church members (immigrant and local) didn't know who Champollion was. And why would anyone label Joseph as a "Champollion"? As Jeff has shown us over the past months, he wasn't a decipherer, he translated the BofA by revelation. The GAEL appears to have been an intelligent failed experiment, an attempt to reverse engineer, as Nibley and others have pointed out for over half a century.

I'll probably be very busy for a while, so will say “bye” after I wrap up a few things, and I'll give a few explanations here (unless someone starts something :)):

1- anonymous commentators who don't dare admit their affiliations (MT, IRR, etc.) are often "not ok"

: ), even if they sign 'OK" after comments they are particularly proud of.

2- "no brainer" means, it's so easy to see the truth that even a critic could believe, if they weren't afraid or ashamed of it : ).

luv ya'll

“there's about a 99% chance that Joseph read the article where they talked about Champollion“

Please note that this article was published with the already translated text. Knowledge of Champollion at this point would have no bearing on the translation process.

“there's little chance that Joseph Smith and Church members (immigrant and local) didn't know who Champollion was“

This is the purest of speculation on your part since nobody mentioned him in anything we have record of.

And secondarily, there is no reason to believe that they were aware of what his work actually entailed as that was disputed for years after his death. It wasn’t for years that the correctness of his theories and interpretations was ultimately proven. The article Jeff cites above shows that the British thought Young had the right of things for quite some time.

Jeff, I must agree with one of the anonymous commentators above. You seem to have missed Ritner’s point as well as the point of the 1842 New York Herald article cited by Ritner. Glidden was taking advantage of the general public’s ignorance and pretending Champollion’s work was his own. The letters Tasistro threatened to publish were no doubt in French.

I don’t think Ritner was saying that Champollion and his decipherment of the Rosetta Stone were unknown in America, only that the details of the decipherment were “generally” unknown.

Jensen and Hauglid merely state: “There is no evidence that Joseph Smith or his associates had read contemporary works of French or English Egyptological scholarship, but they nevertheless seemed to approach the papyri with many assumptions that were espoused by scholars who wrote before Champollion.” (p. xvii)

We don’t know if Joseph Smith knew about Champollion in 1835. I doubt it. However, we do know that Joseph Smith was told by Chandler that none of the learned he consulted in the East could decipher the writing on the papyri. From this, Smith no doubt concluded that he could not be exposed.

The works of Nibley, Gee, and Muhlestein are worthless when it comes to the Kirtland Egyptian papers. None of them understood the original documents. Jensen and Hauglid understand them better. If they were to cite these three apologists, it would have only been to correct the misinformation they have disseminated.

Ritner is cited by Jensen and Hauglid mostly because of his book published by Smith-Pettit is groundbreaking and the most authoritative publication on the subject of the Joseph Smith papyri. None of the apologists have published anything remotely like it.

“Smith no doubt concluded that he could not be exposed.“

I’m starting to be of the opinion that this is why the translation took so long and why Joseph attempted a more traditional translation first (including trying to learn Hebrew—which was thought to be close to the Adamic language, as was Egyptian) He may have had an inkling that hieroglyphics were on the verge of being cracked and didn’t want to risk the exposure.

Do we have any further evidence as to the impetuous of the purchase? Did Joseph request that the Egyptian collection be purchased or was he provided with the documents by members wanting to see his gift of translation in action? I can see his ego forcing him to request the documents to provide him with a reason for a new translation, but I can also see him feeling great pressure to translate the documents that members spent a small fortune to purchase. To me, the documents “surprisingly” containing records of Abraham and Joseph are evidence that he clearly knew his knowledge of Egyptian culture was much more limited than his knowledge of Hebrew culture. It’s one thing to claim to be able to translate Egyptian—it’s another to be able to correctly mirror the culture. He solved this problem by having his Egyptian documents contain Hebrew themes.

Dan said: "Ritner is cited by Jensen and Hauglid mostly because of his book published by Smith-Pettit is groundbreaking and the most authoritative publication on the subject of the Joseph Smith papyri. None of the apologists have published anything remotely like it." Do you mean that no one else has published a translation of the papyri? Of course not, since Rhodes has and Nibley did as well. Do you mean that no apologists have published a book that makes lots of sarcastic comments against Joseph Smith? You've got me there. But what other aspects of Ritner strike you as so unique?

For further evidence regarding knowledge of Champollion among the early members of the Church, see my latest post: "Is There Direct Evidence that the Early Saints Had Heard of Champollion?," Aug. 25, 2019.

Dan said, "The works of Nibley, Gee, and Muhlestein are worthless when it comes to the Kirtland Egyptian papers. None of them understood the original documents. Jensen and Hauglid understand them better."

If you define "understanding better" as "agreeing better with Dan Vogel," then you're absolutely right. But if "understanding the documents" includes understanding the relationship between the KEP and the Book of Abraham, or the understanding the way prior scholars have analyzed and treated the documents, or understanding dates of production or purpose or authorship of those documents, then there may be a problem.

John Gee's review of their volume raises some pretty serious issues about their work, I'm sorry to say — the most visible of which is the relatively minor issue of printing two documents upside down. (I don't think that particular gap can be debated now that it has been pointed out.) To me, though, the bigger issue is getting key documents backwards (in terms of the relationship between the KEP and the Book of Abraham).

Dan said, "I don’t think Ritner was saying that Champollion and his decipherment of the Rosetta Stone were unknown in America, only that the details of the decipherment were “generally” unknown."

Here's what Ritner wrote: "…1842, well before Jean François Champollion’s correct decipherment of Egyptian was generally known in America." Any reasonable reading of this passage, IMHO, suggests that Ritner is talking about knowledge of the decipherment, or in other words, the news of the decipherment (that news included the fact that there is a phonetic aspect to Egyptian). Ritner appears to be discussing the headlines, not the scholarly details, and he supports his claim with an article that speaks of how news of Champollion is becoming widely known and that clearly is NOT making an announcement of Champollion's discovery or introducing Champollion to the world — that is clearly common knowledge by then, just as it was years earlier in Palmyra, New York, Ohio, and Pennsylvania.

Details? The scholarly details still aren't "generally known" in the United States or anywhere else. Champollion actually did not even decipher the Rosetta Stone, just parts of it. It wouldn't be until long after his death that the translation would be published in the late 1850s.

Ritner's comment only makes sense as a teaching (though erroneous) that news of Champollion's breakthrough was not generally known in the US by 1842, but the cat was out of the bag in the US by no later than 1827 when the widely read Niles Register reported the story, and news of the Rosetta Stone was out before that. The rise of Egyptomania was fueled by these "generally known" matters. You can't have Egyptomania gripping the Saints in 1835 in complete ignorance of the big news fueling Egpytomania: Champollion and the Rosetta Stone.