Quick overview: Doctrine and Covenants 9 refers to a time when Oliver Cowdery had permission to attempt to translate the Book of Mormon. He “began to translate” (Doctrine and Covenants 9:5), but failed, apparently due to fear (v. 11) and lack of faith. But when he began translating, what was he doing? This episode happened in April 1829, early in Oliver’s scribal work, well before he received permission to see the gold plates and become one of the Three Witnesses in June 1829. Since he was not yet able to see the gold plates, what did his translation attempt entail? Surely it involved looking into the Urim and Thummim (a term later applied to the translation process that often refers to the Nephite “interpreters” but can also apply a single seer stone owned by Joseph) but without the plates open before him. This is scriptural evidence that refutes the notion that the translation necessarily involved looking directly at the gold plates through the transparent Nephite interpreters rather than looking into a single seer stone in a hat.

Here we also consider the common misinterpretation of Doctrine and Covenants 9:7-9 that has led to the awkward and implausible theory of looking at a foreign language in an unknown script to “study it out” in one’s mind to propose a translation in one’s own words, that can then be confirmed in prayer. Based on related suggestions from Stan Spencer and Kendra Lindsay, the “it” in “study it out” is more reasonably understood as the question of whether it is right or wrong to translate (or more specifically, perhaps, was the time right and the translator ready?). It was not a question about a proposed translation of characters created by much mental effort from someone who had not yet even seen the plates. Indeed, the idea of translating by iteratively forming proposals for a translation of an unknown script would be a slow, tedious process that is completely inconsistent with how Joseph translated and with the remarkable characteristics of the text his rapid work produced.

Translation by “Studying Out” an Unknown Script Conveying an Unknown Language?

How did Joseph translate the unknown script of an unknown language on the gold plates? Starting perhaps with B.H. Roberts (see my recent book review on a particular translation theory), many people have applied Doctrine and Covenants 9:7-9 to propose a method based on intense mental effort that would lead to some kind of inspired impression that then needed to be expressed in Joseph’s own words which would then need to be confirmed in prayer. Translation is hard enough when a translator understands the script and the language. Yet Joseph dictated the text to his scribes (mostly Oliver Cowdery) at a rate higher than typical professional translators can do for a sustained period of time. He did so without notes, without major revisions, hour after hour. During the approximately 60 days devoted to translation work from April 1829 to June 1829, after he started anew following the loss of the 116 pages of initial translation, Joseph would dictate over 269,000 words, giving a pace of about 4,500 words on average per day of translation, in contrast to the typical professional translation rate of around 2,500 words per day (see the discussion here, here. here, and here).

How did Joseph translate the unknown script of an unknown language on the gold plates? Starting perhaps with B.H. Roberts (see my recent book review on a particular translation theory), many people have applied Doctrine and Covenants 9:7-9 to propose a method based on intense mental effort that would lead to some kind of inspired impression that then needed to be expressed in Joseph’s own words which would then need to be confirmed in prayer. Translation is hard enough when a translator understands the script and the language. Yet Joseph dictated the text to his scribes (mostly Oliver Cowdery) at a rate higher than typical professional translators can do for a sustained period of time. He did so without notes, without major revisions, hour after hour. During the approximately 60 days devoted to translation work from April 1829 to June 1829, after he started anew following the loss of the 116 pages of initial translation, Joseph would dictate over 269,000 words, giving a pace of about 4,500 words on average per day of translation, in contrast to the typical professional translation rate of around 2,500 words per day (see the discussion here, here. here, and here).

But doesn’t Doctrine and Covenants 9 make it clear that Joseph had to intensely study out the translation in his own mind and get a burning in his bosom when he had the right translation? The key verses with the “study it out” passage are vv. 7-9, but let’s consider the context from vv. 1 to 12:

1 Behold, I say unto you, my son, that because you did not translate according to that which you desired of me, and did commence again to write for my servant, Joseph Smith, Jun., even so I would that ye should continue until you have finished this record, which I have entrusted unto him.

2 And then, behold, other records have I, that I will give unto you power that you may assist to translate.

3 Be patient, my son, for it is wisdom in me, and it is not expedient that you should translate at this present time.

4 Behold, the work which you are called to do is to write for my servant Joseph.

5 And, behold, it is because that you did not continue as you commenced, when you began to translate, that I have taken away this privilege from you.

6 Do not murmur, my son, for it is wisdom in me that I have dealt with you after this manner.

7 Behold, you have not understood; you have supposed that I would give it unto you, when you took no thought save it was to ask me.

8 But, behold, I say unto you, that you must study it out in your mind; then you must ask me if it be right, and if it is right I will cause that your bosom shall burn within you; therefore, you shall feel that it is right.

9 But if it be not right you shall have no such feelings, but you shall have a stupor of thought that shall cause you to forget the thing which is wrong; therefore, you cannot write that which is sacred save it be given you from me.

10 Now, if you had known this you could have translated; nevertheless, it is not expedient that you should translate now.

11 Behold, it was expedient when you commenced; but you feared, and the time is past, and it is not expedient now;

12 For, do you not behold that I have given unto my servant Joseph sufficient strength, whereby it is made up? And neither of you have I condemned.

Looking now at v. 8, the key question is what does “it” refer to when Oliver is told “that you must study it out in your mind; then you must ask me if it be right, and if it is right I will cause that your bosom shall burn within you; therefore, you shall feel that it is right.”

We’ve long assumed that the antecedent of “it” is the translation of text on the gold plates, though the first “it” may be the foreign characters themselves that must be studied to get a proposed translation, somehow guided by the Urim and Thummim (a term that can include both the Nephite interpreters and Joseph’s own seer stone), which then becomes the “it” that needs to be confirmed in prayer to see if “it” is right. But in an important work of scholarship, Stan Spencer carefully examines the language here and makes a compelling argument that vs. 8 is not talking about the mechanics of translation, but about the question of whether or not it was right at that time to translate. See Stan Spencer, “The Faith to See: Burning in the Bosom and Translating the Book of Mormon in Doctrine and Covenants 9,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 18 (2016): 219-232.

Spencer first gives four reasons to question the traditional interpretation of “study it out in your own mind”:

First, neither study nor spiritual confirmation is mentioned as a requirement for translating in the instructions to Oliver Cowdery in section 8 or anywhere else in scripture. Second, before his attempt to translate, Oliver Cowdery had been promised that he would be able to translate “according to [his] faith” (D&C 8:11). Based on this promise, his lack of success would have been due to lack of faith, not improper technique. Third, Doctrine and Covenants 9:5 observes that Oliver Cowdery “began to translate,” which suggests that he actually did translate and must have known how to do so. Fourth, Doctrine and Covenants 9:8 indicates the need to “study it out” and ask “if it be right,” but there is no obvious antecedent for the pronoun it in the revelation that is consistent with the conventional theory.

Spencer then explores the antecedents for “it” in Section 9 and determines that the most reasonable interpretation is that the issue is not how to translate, but whether it was the Lord’s will for Oliver to translate. Spencer concludes that “Doctrine and Covenants 9:7–9 teaches us how to obtain a spiritual confirmation of a righteous desire.”

A related but alternate approach, shared with me by Kendra Lindsay, my wife, is that ultimately Oliver’s need was to have the faith and power to translate, which required more than looking into a stone or stones. It required prayerful preparation that he might be able to receive the revelation needed for the translation. Being attuned with God may have been the key to the translation, and only then would he be able to look into a Urim and Thummim to see the written translation. If so, what he should have studied out in his mind might have been how to act as a seer, or rather, if he then had the faith and closeness to God to perform as a seer. While Spencer’s approach might summarize the “it” of Doctrine and Covenants 9:8 as “Is it right for me to translate now?,” my wife’s approach might put the question as “Am I right before God and ready to translate?” Perhaps the two can be united with the question, “Is the time right and the translator ready?”

Viewing the question that faced Oliver in this way makes more sense in understanding the miraculous translation of the Book of Mormon. It makes sense of the rapid pace of not just translation, but of dictating and writing the text. For example, John W. Welch conducted trials with other people to see if a practical pace of speaking and writing could fit the data. He determined that rates between 10 to 20 words per minute were practical and would require from about 4 to 8 hours per day. See John W. Welch, “Timing the Translation of the Book of Mormon: ‘Days [and Hours] Never to Be Forgotten,’” BYU Studies Quarterly 57, no. 4 (2018): 37-39. The paces Welch considered did not include estimates of time for studying out characters in Joseph’s mind, proposing a translation, and then getting confirmation in prayer before dictating the final, confirmed text. Such steps would considerably slow down the translation process.

A rapid translation, without the need for studying, pondering, and seeking confirmation or reworking the translation, also better fits subtle evidence about the translation process that can be extracted from study of the dictated text that gave us the Original Manuscript of the Book of Mormon. See Stanford Carmack, “Joseph Smith Read the Words,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 18 (2016): 41-64. A rapid translation through the Urim and Thummin (or seer stone) also better fits mechanics that we can infer from the flow of text in the Original Manuscript of the Book of Mormon which suggests that Joseph saw the text provided in discrete chunks of around 20 words at a time, not a couple of carefully pondered and prayed-about characters. See Royal Skousen, “The Witnesses of the Book of Mormon,” in The History of the Text of the Book of Mormon, vol. 3, part 7 (Provo, UT: BYU Studies, 2024), 68–69. (A preprint is available on the Interpreter Foundation blog, where the relevant material is on pp. 28-29.)

The translation process involved looking into a revelatory tool and apparently seeing the translation, which was then read to the scribe. This is consistent with the Lord’s statement in (2 Nephi 27:20, 22, 24) which three times says that Joseph will “read the words” that would be given him. This is, after all, the unique role of a seer: to obtain revelation by seeing with divine power. The seer stone or Nephite interpreters (two seer stones set in a frame) could help a seer to see and translate, though Joseph could later do translation without that aid (e.g., the Joseph Smith Translation of the Bible was apparently done without the use of seer stones). What Joseph saw, as far as we can tell, was a written translation when he looked into a revelatory aid. But in considering Section 9 of the Doctrine and Covenants, an important question arises: What did Oliver see? Or rather, what did he look at in his translation attempt?

The Mechanics of Oliver’s Translation Attempt

While Doctrine and Covenants 9:7-9 may not tell us about the mechanics of translation, there is a valuable implicit clue about the translation mechanics in v. 5:

And, behold, it is because that you did not continue as you commenced, when you began to translate, that I have taken away this privilege from you.

He began to translate, but how? What was he looking at to do this?

There are two reasonable possibilities for this April 1929 event: (1) he looked into the Nephite interpreters, as Joseph may have been doing at the time or certainly had done, or (2) he looked into a seer stone. But it seems that we can be certain he was not looking through the Nephite Urim and Thummim at the plates in an attempt to decipher a foreign script and come up with proposals to test in prayer. Why? Because Oliver had not yet become a witness to the plates, which would not happen until June 1829. He did not yet have permission to look at them. Thus, whichever form of a seer stone Oliver was attempting to use, one or two from the Nephite interpreters or one of Joseph’s non-Nephite seer stones, he wasn’t looking at the plates. So what was he doing? If he were using the Nephite seer stones, perhaps he was following the method that faithful Latter-day Saint Joseph Knight Senior described Joseph’s work:

Now the way he translated was he put the urim and thummim into his hat and Darkned his Eyes then he would take a sentance and it would apper in Brite Roman Letters then he would tell the writer and he would write it then that would go away the next sentance would Come and so on [emphasis added]

A source for this is Joseph Knight Senior, reminiscence in his own hand dated between 1835 and 1847 (the year of his death), as cited by Skousen, “The Witnesses of the Book of Mormon,” p. 62.

Whether it was the Nephite dual-seer-stone Urim and Thummim (of which only one seer stone might have been used at a time) or a single seer stone, the only way that seems to work for an attempted translation was for Oliver to be looking into a seer stone. How? If he was not able to look at the plates, then what? Then he may have done what so many witnesses saw Joseph doing: looking at the seer stone(s) in a hat. I don’t know that for sure, but it seems clear he was not staring at the plates that he was still forbidden to see.

Since this was Oliver’s first attempt at translation, it would make sense that Joseph allowed him to use the “premier” and impressive faith-promoting translation tool, the original Nephite Urim and Thummim, perhaps to have the best shot at success, but that’s just speculation. Either way seems possible. But if Joseph was using the Nephite interpreters at the time and shared them with Oliver (with divine permission, of course), then Oliver would have been translating at a time when the Nephite tool was in use. Joseph may have started relying on the seer stone shortly after this to account for the witness statements about the seer stone.

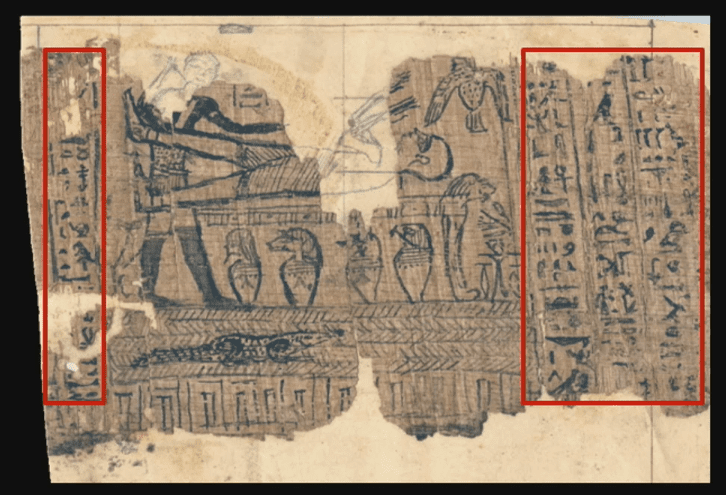

Doctrine and Covenants 9 turns out to be more important than I previously appreciated. Here it seems that canonized scripture gives us an important clue that makes the possibility of a hat being used even more plausible, for it is now clear that staring at the plates was certainly not required. Just as modern translators of ancient texts such as the Dead Sea Scrolls often work with digitized images viewed on a displayed screen, so Joseph and Oliver may have been able to translate without the gold plates open before them. They were vital sacred relics testifying to the reality of the Nephites, the divinity of the record, and the ministry of Jesus Christ, but did not have to be constantly viewed and handled for the divine translation process. Translating from them with a revelatory tool is no affront to the sanctity of that record, as some have claimed, no more than scholars translating from computer images of the real, tangible Dead Sea Scrolls is an affront to that precious record and the people who wrote it.

If Oliver used a revelatory tool to attempt his translation without the gold plates in sight, why should believers of the Book of Mormon grumble about historical insights into the diverse modes of translation that Joseph Smith employed, as discussed in the Gospel Topics Essays entry on “Book of Mormon Translation“? That scholarly essay acknowledges the unnecessarily controversial use of a single seer stone during the translation of the Book of Mormon, in addition to the use of the Nephite interpreters.

It’s wise to keep in mind how diverse Joseph’s work as a seer was when it came to translation. Joseph’s translation of the Bible was done without the Greek or Hebrew before him and apparently without the use of a revelatory aid like the Urim and Thummim. Before Oliver’s translation attempt in April 1829, Joseph had inquired through the Urim and Thummim and was shown the translation of a hidden parchment written by John, giving us Doctrine and Covenants 7. Again, Joseph saw a translation without having the source document anywhere near him. Likewise for the Book of Abraham, we aren’t sure whether the Joseph Smith papyri contained the text that was revealed to Joseph as the Book of Abraham. Joseph and his peers were obviously interested in studying out the meaning of the Egyptian script, but that was an apparently unsuccessful process which appears to have begun after the translation was done, not as a precursor to translation. Clearly there was great diversity in Joseph’s role as a translator, but no evidence that it included first studying out foreign scripts and languages to gradually come up with translations. We must be careful about our demands of what “translation” must be and how it must have worked.

The Book of Mormon is a marvelous work and a wonder that defies all attempts to explain it as Joseph’s work. It was delivered by divine means in a flood of revelation. We don’t know exactly what Joseph saw and perceived during the various stages of the translation process. However, we can see and should celebrate the results. A miraculous, rapid translation was provided that continues to startle and reveal new insights for those who take it seriously. It is a powerful witness of Jesus Christ, translated by a seer through the gift and power of God.